Joe Rimkus. Miami News Collection, HistoryMiami Museum.

Audio By Carbonatix

On August 11, 2017, a group of white supremacists gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the scheduled removal of a statue of Confederate icon Gen. Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park. With tension mounting in the city, the so-called Unite the Right rally turned violent the following day, when heated clashes erupted between alt-right protesters and anti-racist, anti-fascist counterprotesters. The chaos culminated when alleged Nazi sympathizer James Alan Fields Jr. of Ohio plowed his car into a crowd of counterprotesters in the street, injuring 19 and killing Heather Heyer of Charlottesville.

The rally wasn’t the first of its kind since President Donald Trump took office in January. In May and July, white supremacists and the Ku Klux Klan had also convened in the city to rally their cause.

Here in Florida, racism is hardly new – and neither is black resistance. South Florida is geographically distant from the Deep South but was always, as HistoryMiami Museum’s resident historian, Paul George, puts it, “mired by a fractiousness of relations between races” influenced by the white South’s deeply rooted legacy of racial oppression.

“Police and blacks suffered fraught relations for generations since 1896,” George continues. “Miami was the Deep South in [terms of] racism. People came out to lynchings in Homestead and Fort Lauderdale in the ’20s and ’30s like it was a party.”

Historian Chanelle N. Rose, author of the book The Struggle for Black Freedom in Miami: Civil Rights and America’s Tourist Paradise 1896-1968, says Miami was unique because of its connection to the Caribbean and Latin America, which grew strongly in the years following World War II. Latinization eventually tempered some of the racial explosiveness of infamously segregated cities such as Birmingham, Alabama. “Promoting Miami as a pan-American city, the ‘gateway to the Americas,’ had an impact,” Rose explains. “Business leaders had to deal with racial hostility and tension differently than in Southern cities. Miami without tourism would’ve crippled the economy.” According to Rose, the white civic elite adopted a more sophisticated form of white supremacy to appease blacks and deter racial violence.

Nevertheless, as George, Rose, and fellow historian Marvin Dunn, author of the book Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, contend, Miami’s voluminous history is intrinsically connected to the evolution of black history in the United States and doesn’t exist in a vacuum. In light of the recent event in Charlottesville, New Times asked the three scholars which events in Miami’s black history stand out as key moments of black resistance.

Cape Florida Lighthouse in Key Biscayne, circa 1920.

(State Archives of Florida/Fishbaugh)

1790s to 1860s: Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad was a covert network of slaves and abolitionists who provided the means for African-American slaves to escape from bondage. Its most famous conductor, Harriet Tubman, helped many slaves escape to abolitionist strongholds in the north, but many blacks headed south, where Bahamian fishermen turtling on Key Biscayne helped them and “black Seminoles” – black slaves who integrated with Florida’s native population or were the product of interracial coupling. From there, they crossed the Florida Straits to Red Bays and other freed-slave communities in the Bahamas. Many slaves embarked on their journey to freedom in what is today’s Cape Florida at the tip of Key Biscayne’s Bill Baggs State Park, where a historical marker identifies the island as an officially designated National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site.

Chauffeur Charlie H. Moore in Lovett, Florida, 1925.

1917: Chauffeurs’ Riot. As more snowbirds began traveling to Florida with their black chauffeurs, they encountered racist laws that essentially put the drivers out of a job. Out-of-town chauffeurs couldn’t work for their private clients south of Miami’s northern boundary at NW 20th Street. At the border, a white chauffeur would take over driving duties, sometimes for the whole winter. Black chauffeurs had no choice but to wait or seek temporary employment elsewhere and return at the end of their employer’s winter break. Black drivers were able to chauffeur black passengers, but only in Colored Town (know today as Overtown). Besides, the good money, Dunn says, was in white tourism: “Miami was a tourist town, and being a chauffeur to whites was a high-class job back then.” Competition for the coveted positions was fierce, and tension resulted in street fights, arrests, and riots. “The newspapers described the street melees as white chauffeurs chasing blacks like a pack of hounds chasing a rabbit,” Dunn says.

1939: City of Miami Elections. During the contentious election of 1939, black civic leader Sam Solomon encouraged an unprecedented group of nearly 2,000 registered black voters to head to the polls despite harassment from the KKK, which intimidated residents of Colored Town by staging motorcades with hooded Klansmen, mock lynchings, and cross burnings. Solomon was running for city commissioner, and although he lost, his efforts galvanized the black community and inspired Harlem Renaissance poet and activist Langston Hughes to write “The Ballad of Sam Solomon” four years after the election. Solomon was also known as the “Moses of Miami” for his role as president of the Negro Citizens’ Service League.

Group at Virginia Key’s segregated beach.

1945: Wade-in at Haulover. During World War II, the U.S. Navy trained white sailors at Crandon Park, which was then a white-only beach. Segregation forced black sailors to train across Bear Cut on Virginia Key’s beaches, which were designated solely for that purpose. After the war, all of Dade County’s beaches became once more off-limits to blacks. A small group of black civic leaders organized and led a wade-in farther north at Baker’s Haulover Beach to protest the closure of Virginia Key, which took place without incident. Less than a month later, on August 1, 1945, Virginia Key opened as the city’s first and only colored beach.

Bombing of Carver Village in Miami, Florida, on November 30, 1951.

1951: Carver Village Bombings. In 1951, Miami residents, both black and white, voted in favor of slum clearance and public housing. But white residents still didn’t want to live with or near blacks, which exacerbated the housing shortage. Racial tension and violence ensued, with KKK members distributing flyers, among other intimidation tactics, to keep black Miamians in segregated ghettos. The Carver Village buildings, located on the NW 6800 block of Tenth Avenue in the Edison Center section of Miami, was opened to black residents in August of that year; the area suffered numerous dynamite bombings from September to December. Fortunately, no one was injured. White supremacists, who stocked up on ammunition and arms, also bombed a synagogue, and that anti-Semitic terrorism strengthened an interracial alliance between Jews and blacks fighting racial violence and bigotry. An incident connected to the Carver bombings would later “energize black Florida,” according to Dunn, when a bomb killed NAACP leader Harry T. Moore and his wife at their home in Mims, Florida, on Christmas Day that same year. “It spurred the growth of the NAACP,” Dunn says.

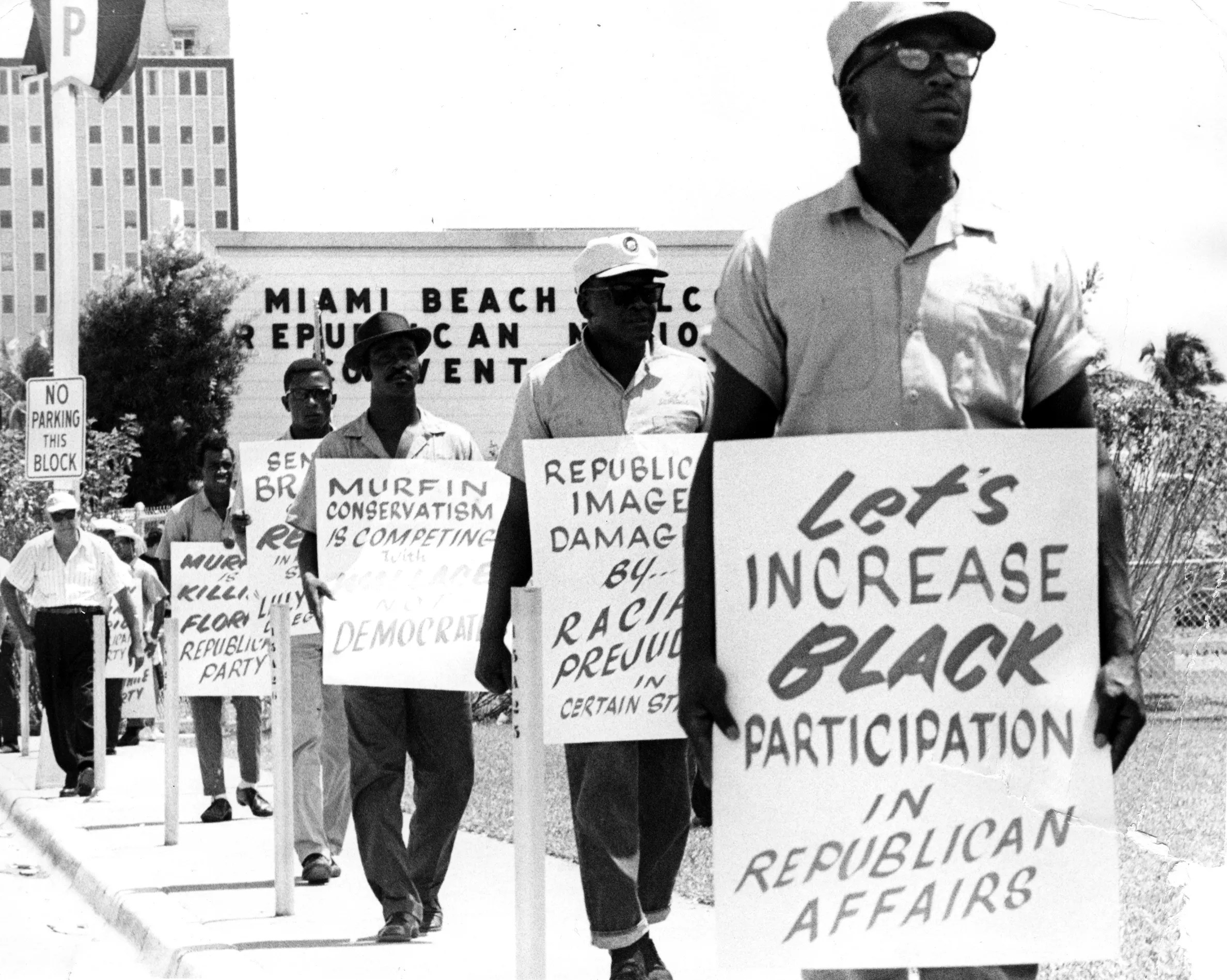

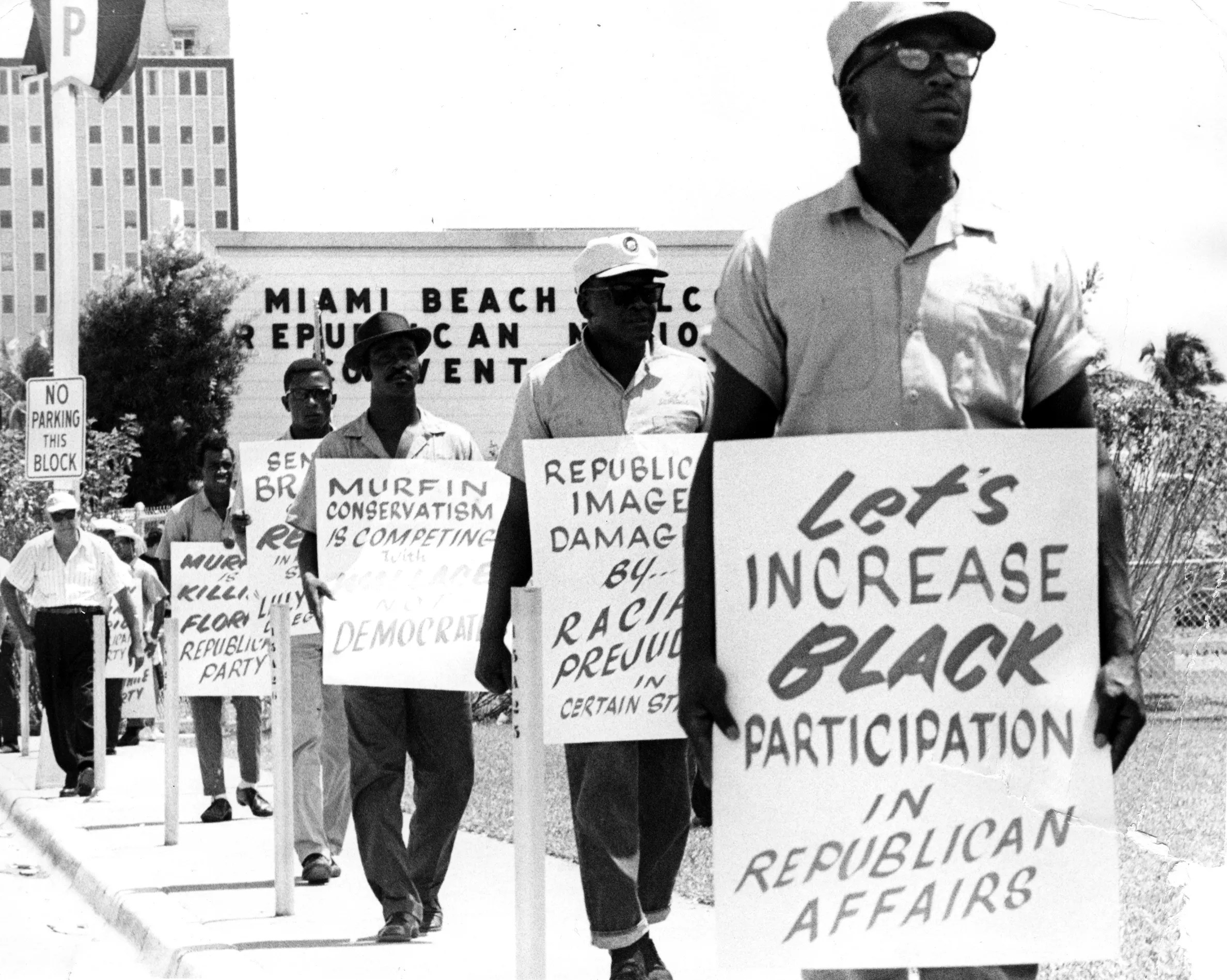

African-American men march outside the Miami Beach Convention Center.

Joe Rimkus. Miami News Collection, HistoryMiami Museum.

1968: Republican National Convention. The 1968 Republican National Convention took place at the Miami Beach Convention Center, where black activists picketed peacefully to protest the lack of attention paid to black issues in spite of the progress evolving from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. In Miami, pent-up tensions over the city’s “stop and frisk” law, poor housing, high unemployment, and increasing government support for Cuban refugees exploded when a white man drove through Liberty City with a bumper sticker promoting George Wallace, an infamous segregationist running against shoo-in Richard Nixon as a third-party candidate. Black residents of Liberty City threw rocks and bottles at the car while they were waiting for Republican basketball star Wilt Chamberlain and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr.’s successor at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to make an appearance at a rally promoted on flyers titled ‘Of Black, by Black, for Black.’ Chamberlain never showed. Rioting continued for two days. The event, according to Rose, revealed that civil rights activists and black nationalists had adopted different tactics to achieve their common cause. Like other parts of the urban North, local black nationalists viewed the Liberty City riots as a racial uprising against decades of oppression.

A guardsman stands ready during the 1980 Miami riots.

1980: Miami Riots. Miami’s most infamous riot, according to George, “was more nuanced and complex, revealing the simmering discontent of the black community toward the criminal justice system and police brutality.” The race riots in Overtown and Liberty City began May 17, 1980, following the acquittal from an all-white male jury of five Metro-Dade Police officers in the death of insurance salesman Arthur McDuffie, who had died from injuries sustained when the officers brutally attacked him after a high-speed chase. The deadly riots – which resulted in a countywide curfew, intervention from the National Guard, and property destruction estimated at $80 million – left an indelible mark on Miami’s history of racial violence. “Now it wasn’t resistance anymore,” Dunn says. “This was a riot. There was no strategy. It was just a spontaneous outburst of violence that wouldn’t have happened if the jury had been racially mixed.” The defense team during the McDuffie trial, which was held in Tampa, took advantage of all peremptory challenges available to eliminate blacks from the jury. “That can’t happen anymore,” Dunn says, “thanks in part to black judge Wilkie D. Ferguson, who wrote the opinion for the appellate court that settled the matter.” Dade County was ultimately ordered to pay McDuffie’s family a settlement of $1.1 million.

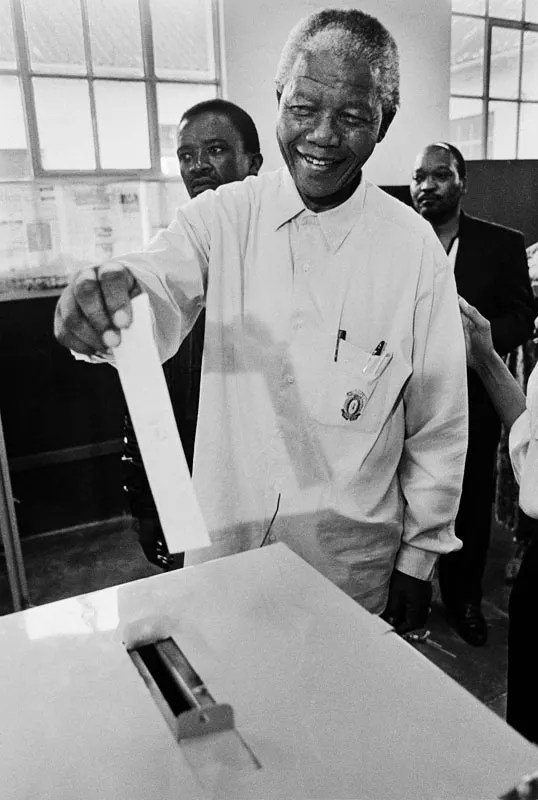

Nelson Mandela in 1994.

Paul Weinberg, via Wikimedia Commons.

1990-1992: Nelson Mandela and the “Quiet Riot.” Nelson Mandela, the South African civil rights leader who was incarcerated for 27 years for working to end apartheid, embarked on a goodwill tour of the world after his release from prison. One of his first stops was Miami, where right-wing Cubans and Jews snubbed his visit because of his willingness to dialogue with Cuban communist dictator Fidel Castro and Palestinian Liberation Organization head Yasser Arafat. In response, black Miami attorney H.T. Smith led a 1,000-day boycott rallying black-owned businesses to withdraw from Miami’s convention industry in Miami and Miami Beach. As a result, the tourism industry lost an estimated $50 million. Miami eventually issued apologies and gave Mandela, who became president of South Africa in 1994, a proclamation. Locally, the “Quiet Riot” showed the essential impact of black contributions on Miami’s economy and culture.