Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

When the Affordable Care Act, also known as the ACA or Obamacare, was enacted in 2010, lawmakers hoped it would help reduce the number of uninsured Americans. That year, an estimated 48.2 million people — about 18 percent of the U.S. population under age 65 — did not have health insurance.

By 2023, the number of uninsured Americans had dropped by nearly 50 percent, to 25.3 million people under 65, or 9.5 percent of the total population.

I’m a gerontologist who studies the U.S. health-care system. ACA health-care subsidies are at the center of a now-monthlong U.S. government shutdown that could become the longest in U.S. history. So I looked at the available data about ACA marketplace plan usage in Florida to understand how the debates in Washington could affect access to health care in the Sunshine State going forward.

How the ACA Expanded Access to Health Insurance

The ACA implemented a three-pronged strategy to expand access to affordable health insurance.

One was the use of fines. The government fined anyone — until 2018 — who chose not to get health insurance. The government also fined businesses with 50 or more full-time employees that didn’t offer their employees affordable health-care plans. The idea was to offer incentives for healthy people to get insurance to lower costs for everyone.

Ultimately, the fines had little impact on the number of insured Americans, with one notable exception: The employer-required expansion allowed young adults ages 19 to 25 to remain on their parents’ health insurance plan. For this group, the uninsured rate dropped from 31.5 percent in 2010 to 13.1 percent in 2023.

Second, the ACA allowed for Medicaid to be expanded to low-income Americans who were employed but working in low-wage jobs. The expansion of Medicaid to low-income workers at 138 percent of the federal poverty level was originally required nationwide. But a 2012 Supreme Court ruling allowed states to choose whether they would participate in Medicaid expansion.

As of 2025, 16 million Americans are covered by the expansion. However, ten states, including Florida, have opted out.

The third way the ACA changed the health insurance system is that it established health insurance subsidies that the government can provide. Those subsidies are for low- and moderate-income Americans who do not receive health insurance through their employers and aren’t eligible for Medicaid, Medicare, or any other government-operated health insurance program.

This established a private health insurance marketplace that would include federal subsidies to make insurance more affordable. As of October 2025, more than 24 million Americans currently get their health insurance through the subsidized marketplace.

Florida and the ACA Marketplace

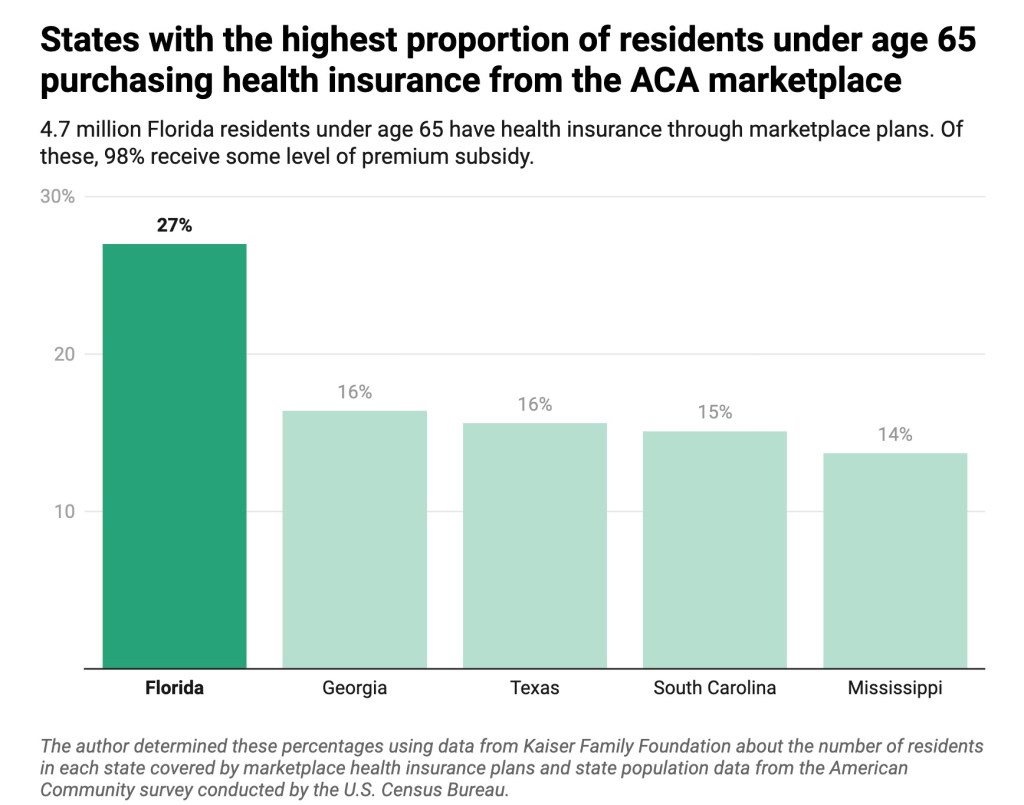

The number of people insured under the ACA in each state varies. But the state with the largest number of residents on marketplace insurance plans is Florida. About 4.7 million Florida residents are covered through these plans, representing 27 percent of the state’s under-65 population, compared to the national average of 8.8 percent. Of those on marketplace plans, 98 percent receive a subsidy at some level.

Chart by Robert Applebaum/Datawrapper

There are several reasons this rate is so much higher in Florida than elsewhere.

First, only 40 percent of Sunshine State residents are covered by an employer-based health insurance plan, compared to 49 percent for the nation as a whole.

This is the lowest rate in the nation. One contributing factor is that Florida ranks fifth in the proportion of workforce that is self-employed, with 1.3 million Floridians in this category.

The state’s lower rate could also be related to the high number of seasonal and part-time workers in the tourism industry.

Another reason is that the state is home to relatively few people enrolled in Medicaid, the federal program that provides mainly low-income people with health insurance coverage. Among Floridians ages 44 to 64, only 11 percent are enrolled in Medicaid, compared to 17 percent for the nation overall.

Florida hasn’t expanded Medicaid, and it’s also more restrictive than most states about who can enroll in the program.

States set their own Medicaid eligibility criteria, and they determine what services Medicaid will cover and at what cost. Florida has the second-lowest Medicaid expenditures per enrollee in the nation, and it ranks last on Medicaid expenditures for adults under 65.

An Uncertain Path Ahead

Because Florida residents rely heavily on marketplace plans, ending ACA subsidies would have a big effect on Floridians.

Unless Congress reverses course and preserves the insurance subsidies that have not been renewed, the average marketplace plan premium is predicted to increase by more than 100 percent, from $74 to $159 per month. An American earning $28,000 annually — $13.50 per hour — would see a fivefold increase, from $27 to $130 per month. And a worker making $35,000 per year would see their premium increase from $86 to $217 per month. [Editor’s note: Florida’s minimum wage rose from $13 per hour to $14 per hour on September 30; it will increase to $15 per hour on September 30, 2026.]

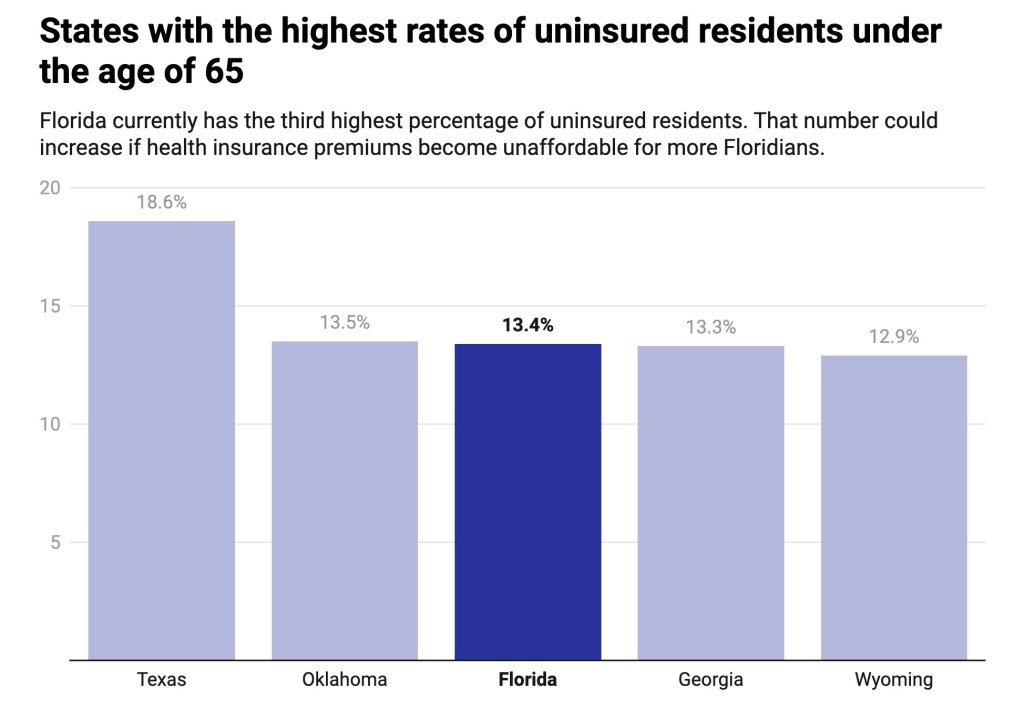

Data via Kaiser Family Foundation; chart via Datawrapper

At 13.4 percent, Florida already has the third-highest proportion of uninsured residents under 65. It is safe to assume that if the federal marketplace subsidies disappear and health insurance premiums become unaffordable for more people, the result will be more uninsured Floridians. And if healthy, younger people can’t afford insurance, premiums are likely to go up for everyone else with insurance.

The path to resolve the ongoing debate is uncertain. In my view, however, it is clear that states such as Florida, Texas, and Georgia, which haven’t expanded Medicaid and rely heavily on ACA marketplace plans, will be dramatically affected by cuts to federal subsidies.

Editor’s note: New Times occasionally shares articles from The Conversation, a nonprofit collaborative whose team of journalists works with academic experts to produce informative opinion and analysis for a general audience. The views expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writer(s). Unless otherwise noted, the content above was produced solely by The Conversation. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.