Photo courtesy of Ann Ferrar, biographer of Bessie B. Stringfield

Audio By Carbonatix

A motorcade of nearly 300 female bikers has left Daytona and is en route to Miami to honor a famous motorcycle matriarch: Bessie B. Stringfield, the Motorcycle Queen of Miami.

On Friday morning, motorcyclists participating in the eighth annual Bessie Stringfield All Female Ride will meet at Stringfield’s last-known residence in Miami Gardens. Alongside officials from Miami Gardens and neighboring Opa-locka, the group will dedicate a nearby road to honor the trailblazing woman biker. The event is open to the community to come and learn about the Motorcycle Queen.

“We work together to honor her memory,” says Lynette “Tabu” Wigfall, historian for the Bessie B. Stringfield All Female Ride Committee. “We don’t want her memory lost. The street we’re looking at is near her last-known residence and I’m not sure that the people in that area know about her history.”

Stringfield was a pioneering motorcyclist in the 1930s and ’40s, and settled down in Miami in the ’50s, where she turned heads as a headstrong Black woman on a Harley Davidson. It was a time when women were relegated to domestic life, and Black residents suffered segregation under Jim Crow laws.

Stringfield’s life and escapades became the stuff of legends – from completing eight cross-country rides when many parts of the nation weren’t friendly to people of color to leading parades as the only female biker honoring Black Miami. She also served as a civilian motorcycle dispatcher for the U.S. Army in the 1940s.

She died in 1993; the American Motorcyclists Association posthumously inducted her into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2002.

Since 2014, the ride committee has gathered a group of women motorcyclists to honor Stringfield by riding cross-country to different locales, sometimes emulating Stringfield’s own “toss a penny” rides by flipping a coin onto a map of the U.S. and choosing the landing point as their destination.

Ann Ferrar, biographer and personal friend of Stringfield’s near the end of her life, says the street dedication is the right thing to do for such an important figure in Miami’s history – a woman who showed courage in the face of segregation in her youth and again when confronting congestive heart disease in her final years.

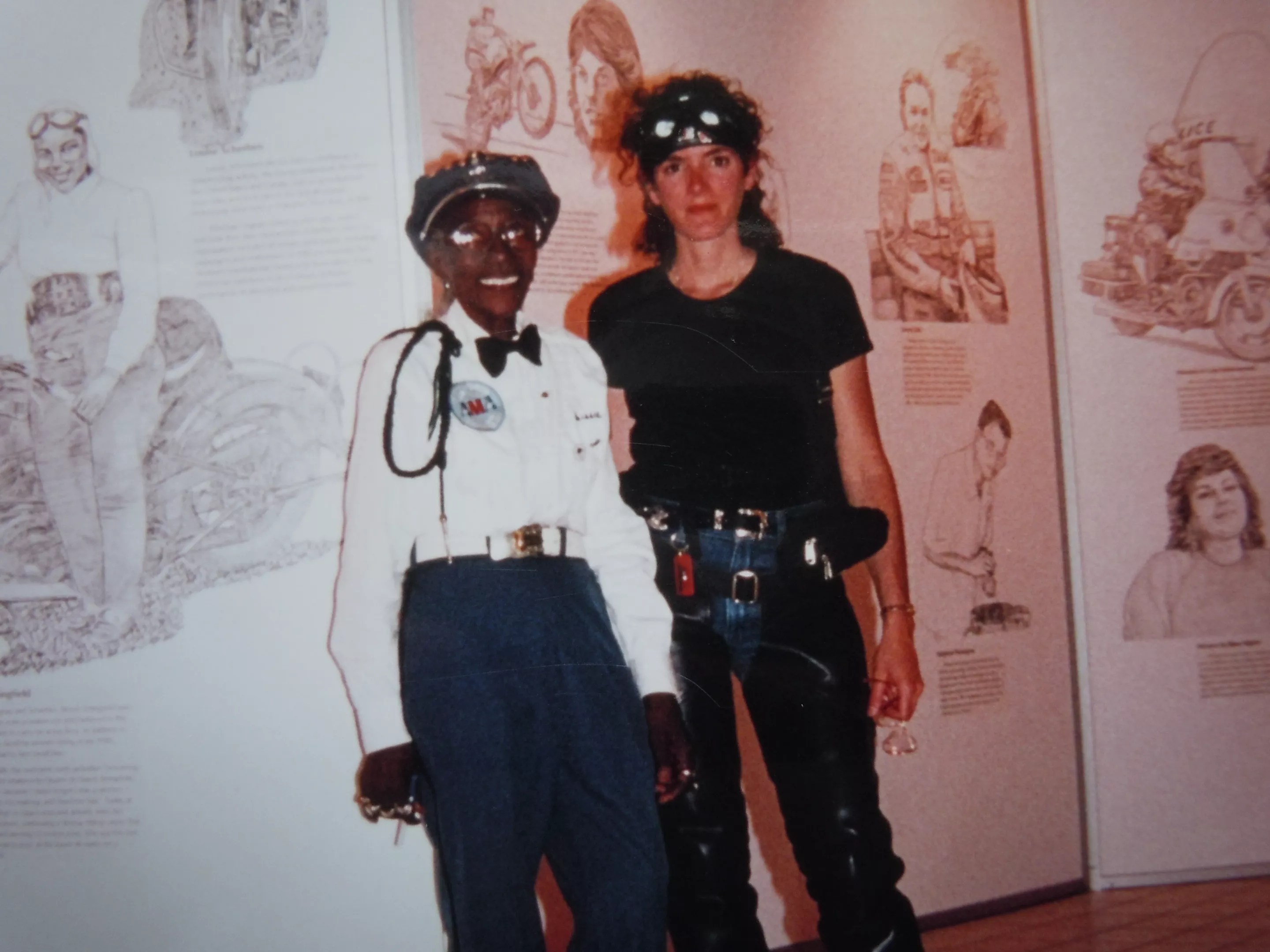

Bessie B. Stringfield (left) stands next to an artist’s depiction of her in the American Motorcycle Heritage Museum alongside friend and fellow biker Ann Ferrar (right).

Photo courtesy of Ann Ferrar, biographer of Bessie B. Stringfield

“As brave as she was when she was riding around the country, she was equally brave as an elderly woman facing a disease that ultimately took her life,” Ferrar tells New Times. “She was a special person, and brave right until the end.”

Much of Stringfield’s known history is recounted in Ferrar’s 1996 book, Hear Me Roar: Women, Motorcycles and the Rapture of the Road, and on her website. Ferrar plans to release a full biography of the Miami Motorcycle Queen, entitled, African American Queen of the Road: Bessie Stringfield – A Journey Through Race, Faith, Resilience and the Road. No clear publishing date has been set.

A documentary crew will film the ride down from Daytona for an upcoming film about Stringfield. Bea Hines, the Miami Herald‘s first Black female journalist, will attend the street dedication. Hines wrote a profile of Stringfield in 1981, regaling local readers with stories of Stringfield winning motorcycle races and her preference for younger men.

The dedication will take place at 10 a.m. Friday, August 20, at Bessie B. Stringfield’s last-known residence located at 2400 NW 152nd Terrace in Miami Gardens.