Miami New Times image

Audio By Carbonatix

Alex Daoud, a fixture in Miami Beach government for a decade before he was laid low by a federal bribery scandal in 1991, has died. This being Miami, news of Daoud’s death might have gone unnoticed were it not for a Sunday-wee-hours Facebook post from Robert “Raven” Kraft (AKA the guy who runs on Miami Beach every single damn day), which was picked up and passed along on social media by Miami Beach City Commissioner Kristen Rosen Gonzalez.

I say “might have gone unnoticed” because both CBS News Miami and, a few hours later, the Miami Herald, attributed the news to Rosen Gonzalez.

I also say “might have gone unnoticed” because the first thing that comes to mind when I think of Alex Daoud is “Daoud Descending,” former New Times staff writer Kirk Semple’s brilliant longform profile of Daoud from 1993. More pointedly, the story’s overarching metaphor tied the disgraced mayor to the myth of Icarus, specifically a 16th-century depiction, Landscape With the Fall of Icarus.

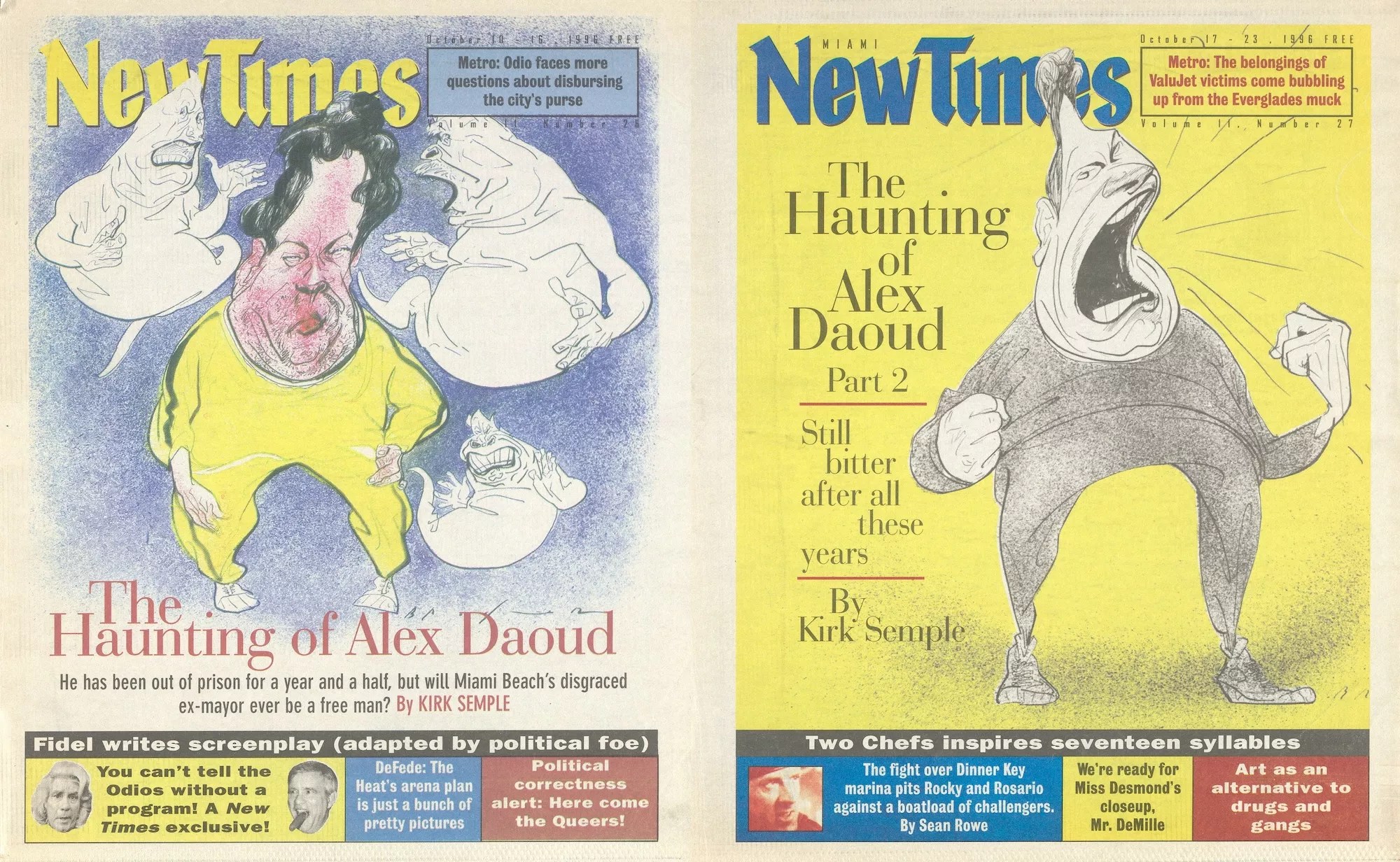

The cover of that issue featured an illustration by Steve Brodner.

Semple went on to write more about Daoud:

- “Bye Bye Birdie,” which recounts a call from the condemned man as his nephew chauffeurs him to the federal penitentiary in Estill, South Carolina, in late November 1993.

- “The Haunting of Alex Daoud, Part 1″ and “The Haunting of Alex Daoud, Part 2,” from late 1996, by which time Daoud was a free man, working on a memoir. Both covers are by Steve Brodner; see above. And Daoud himself weighed in on the coverage with a letter to the editor. (Sad to say, “Part 1” somehow didn’t make it into our electronic archive – an omission that has now been corrected, albeit in pdf form

I pledge to address – by adding it later this week. Check back!) - And New Times was there in 2007 when Daoud read from the aforementioned memoir, The Sins of South Beach, at Books & Books.

- And a month prior, when Daoud turned up at a Miami Beach polling place to exercise his (restored) right to vote.

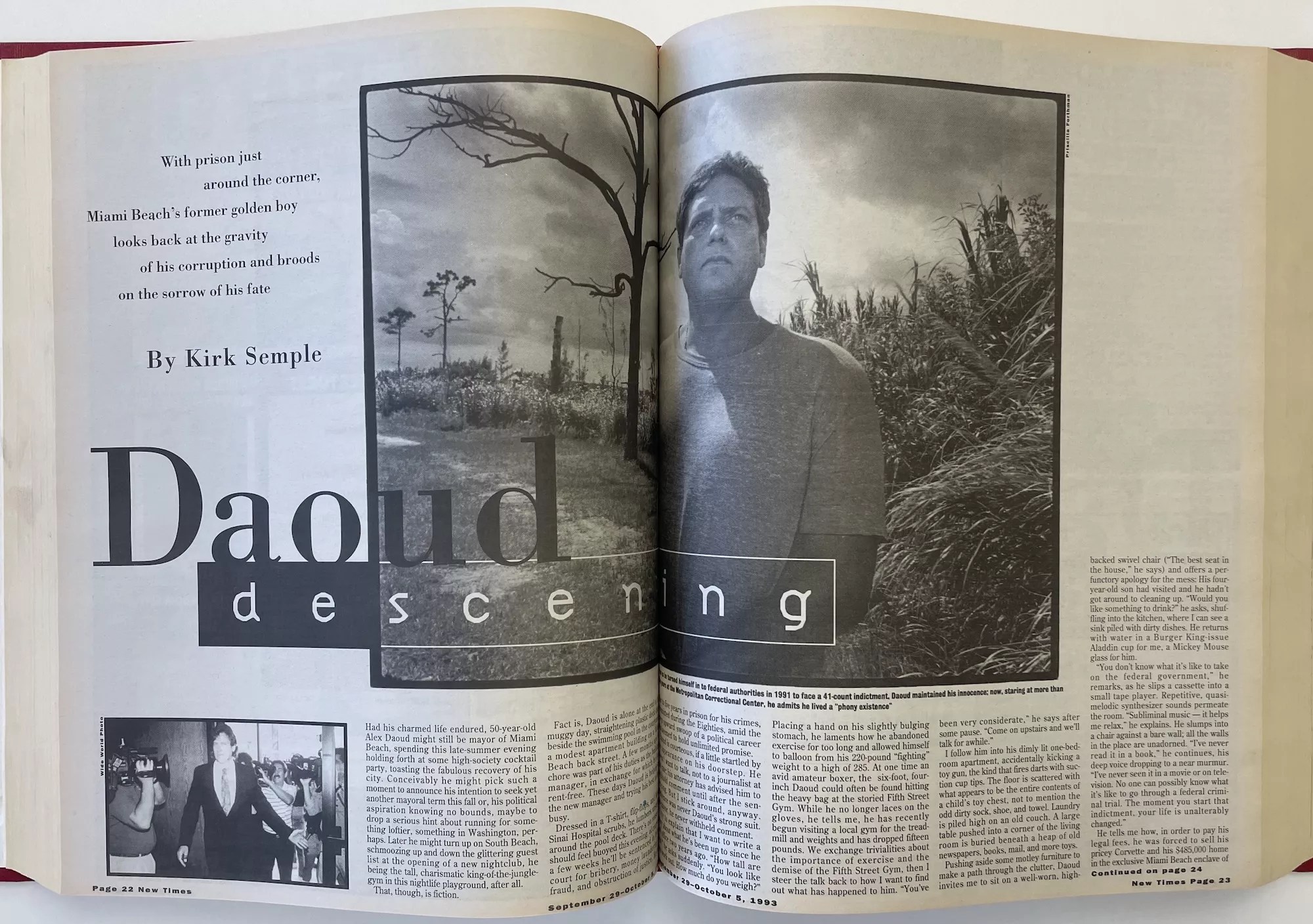

The opening spread of Kirk Semple’s longform feature story, “Daoud Descending,” as it appeared in the September 29–October 5, 1993, issue of Miami New Times

Miami New Times image

But back to “Daoud Descending.” To gather material for the story, Semple spent several weeks hanging out with the ex-mayor, who, at age 50, was awaiting his sentencing hearing on federal counts of bribery, money laundering, fraud, and obstruction of justice.

Here’s Icarus:

Daoud wants me to believe – or wants to believe himself – that he was first led astray by others who took advantage of him, then rudely betrayed. But it’s not that simple. As we spend more time together, he gradually drops his shield.

“I did many stupid things,” he concedes, “most of which I regret, and I will pay for them. I’ve paid for them already; I’ll pay for them the rest of my life. “

We’re back in his apartment. It is in the same state of disarray, but this time, several days after our first meeting, Daoud doesn’t apologize for the mess. A stretch of printer paper cascades off a desk into a mound on the floor; he’s been busy with his book.

He admits that he didn’t give the legal consequences of his actions much thought. “I never saw anything wrong with it. When you’re on the basketball court and you miss a difficult shot, you say, ‘Man, I shouldn’t have taken that shot! Why did I take that shot?’ But if you make it, what do you say? ‘Great! I’ve been practicing that shot all these years! I’ve been dreaming of that shot! I can feel it!’

“I thought I was unbeatable! I felt so good!” he goes on. “But it was also like I was on a merry-go-round and I couldn’t get off. I couldn’t say no. I’ve been trying to think of a mythical character who flew so close to the sun, it melted the wax on his wings and he fell to earth….”

He’s thinking of the Greek myth about Daedalus, a craftsman who built a labyrinth to entrap the Minotaur, only to be imprisoned in his own maze by King Minos of Crete. To escape, Daedalus used feathers and wax to fashion wings for himself and his son, Icarus. Exalting in the joy of flight, Icarus failed to heed his father’s warning and soared too close to the sun, whereupon the wax melted, and the boy plummeted to the sea and his death.

“Icarus,” I say.

“Yes! Excellent! Icarus!” The name is an insect stinging the inside of his throat. Clearly, though, he’s pleased to have nailed the metaphor, as if association with a mythological Greek figure makes his own tragedy more honorable.

To Daoud, accepting a payoff here and a kickback there came with the job. He had convinced himself he deserved it, considering the number of hours he worked and the measly salary he received in return. The mayor of Miami Beach, theoretically a part-time civil servant, is paid only $10,000 per year. Daoud says he made it a full-time job and sacrificed his law practice in the process. “I was trying to help as many people as I could; sometimes I’d take money out of my pocket to help people. I’d pay off their parking tickets. I felt like I should be appreciated as mayor, that I should be compensated for being around.”

Landscape With the Fall of Icarus by Pieter Bruegel the Elder — that’d be Icarus, in the lower right-hand corner, just offshore

Wikimedia Commons image

And here he comes again:

In some retellings of the myth, the death of young Icarus goes unnoticed; even as he plunges downward, his father – and the rest of the world – flies on. Flemish artist Pieter Brueghel’s famous painting of the event, in fact, depicts a plowman, a fisherman, and a shepherd all going about their daily business while a boy’s legs, nearly indiscernible in the background, quietly vanish into the sea.

“As he drove to his sentencing, the defrocked politician contemplated the shambles of his life,” Alex Daoud narrates as he grips the wheel of his monstrous, aging Cadillac Sedan de Ville and speeds across Seventeenth Street toward the causeways and the mainland. His sentencing is scheduled for 1:30 this afternoon, September 8; it’s already 1:10. “But for all his popularity, for all his election successes, he drives to his sentencing alone. Maybe it was fitting that he end his political career in a manner that befits politics. Politics loves a winner. It loathes a loser.”

He’s not nervous, Daoud assures me; he’s relieved that he’ll finally be going to jail so he can get on with his life. He complains about soreness from the morning’s workout and an ankle he twisted during an aerobics session. He ogles a woman on a bicycle (“Oh my God, what’s this up here, this little tidbit?”). He wants to know whether I think he looks strong or just “kind of roly-poly.” But beneath this surface of jocularity, he’s undeniably tense. Back at the apartment he was a bundle of insecurities. “Does my hair look all right?” he’d asked as he dressed. “Does it look okay? Does this tie match this suit?” The brown ensemble was decidedly undapper. The tie was too short and looked as though it had been borrowed from a much smaller man. His white Oxford shirt was wrinkled.

“Do you think I’m going to cry?” he asks, slaloming through the MacArthur’s midday traffic. He smiles. “Do you think they’ll put me in chains right there? They could, you know.” He’s turned nervously eager, like a youngster heading off to camp. “Hey, d’ya think I can take a basketball? D’ya think I can take a tennis racquet? How ’bout my boxing gloves?” It is Daoud’s last day as a lawyer: his suspension from the Florida Bar takes effect tomorrow.

I ask him how he left it with his son. “That was the toughest part,” he replies. “I just told him that I was going away for a while but that I’d see him soon and after that we’d go to medical school together.” Daoud has been teaching the boy the names of all the bones in the body. “He knows I’m going to prison. He’s been singing me a little song. It goes: ‘Bad boy, bad boy, whatcha gonna do? Whatcha gonna do when the law comes for you?'” Daoud clenches his teeth, repeats the words in a slow, hushed tone, ominously. “‘Bad boy, bad boy, whatcha gonna do? Whatcha gonna do when the law comes for you?’ So,” he quips, “you think they’re going to lock me up right there?”

U.S. District Judge James Lawrence King sentenced Daoud to five years. Writes Semple:

“So, do you think I cried?” Daoud asks me later, as we pull away from the courthouse. He didn’t cry, I tell him. “Are you surprised I didn’t cry? Was the media surprised? Hey, was I funny in the elevator?” We cruise through downtown in silence. “Icarus,” Daoud blurts at one point. “Icarus.”

Alex Daoud was freed for good behavior after a year and a half.