Steve Gardner

Audio By Carbonatix

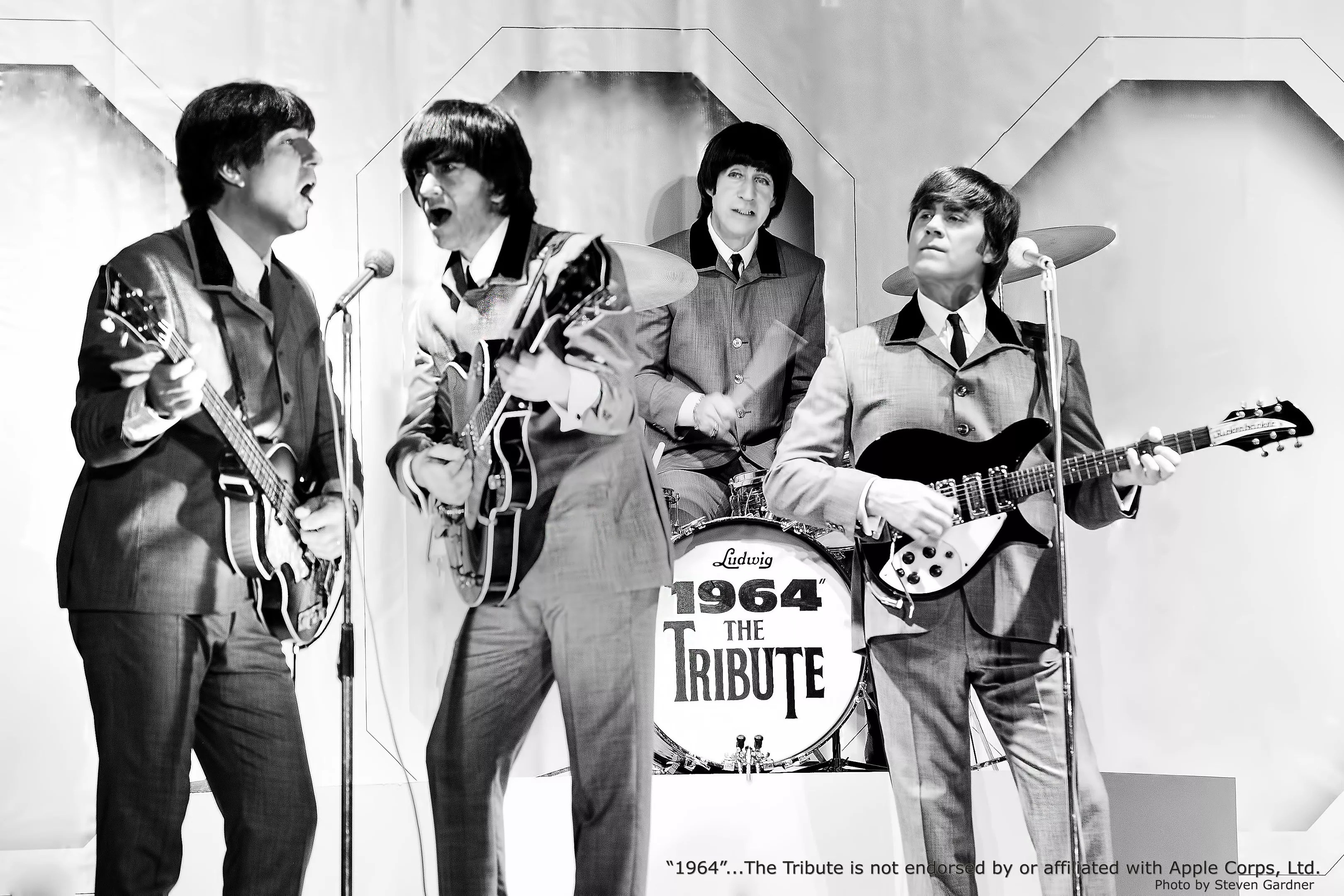

A couple of nights ago, hundreds of Vero Beach baby-boomers piled into the Emerson Center, an 800-seat Unitarian church-cum-concert-hall, for a postprandial show by four men dressed as the Beatles. As the musicians – wearing matching suits, floppy wigs, and silly grins – took the stage, the audience erupted in shrieks. A woman in an Abbey Road shirt shouted from the nosebleeds: “I love you, Paul!”

“Thank you, thank you very much,” the would-be Paul said with consummate McCartney delivery. “I just want to say it’s wonderful to be back here in the colonies.”

A faux Ringo counted off on his drumsticks. The band launched into the opening chords of the Beatles’ 1963 B-side, “I Saw Her Standing There.” The crowd went wild.

Steve Gardner

Tribute music is a multimillion-dollar industry. Last year, the circuit kept more than 7.5 million musicians, sound guys, and stage hands employed, accounting for roughly 3.5 percent of America’s GDP, according to the Wall Street Journal. Within that world, few bands are as widely imitated as the Beatles, who have attracted a reported 29,911 copycat acts. Of that number, the group at the Emerson Center – 1964 the Tribute – ranks among the greatest. In Rolling Stone‘s words, 1964 is “the best Beatles tribute on Earth.”

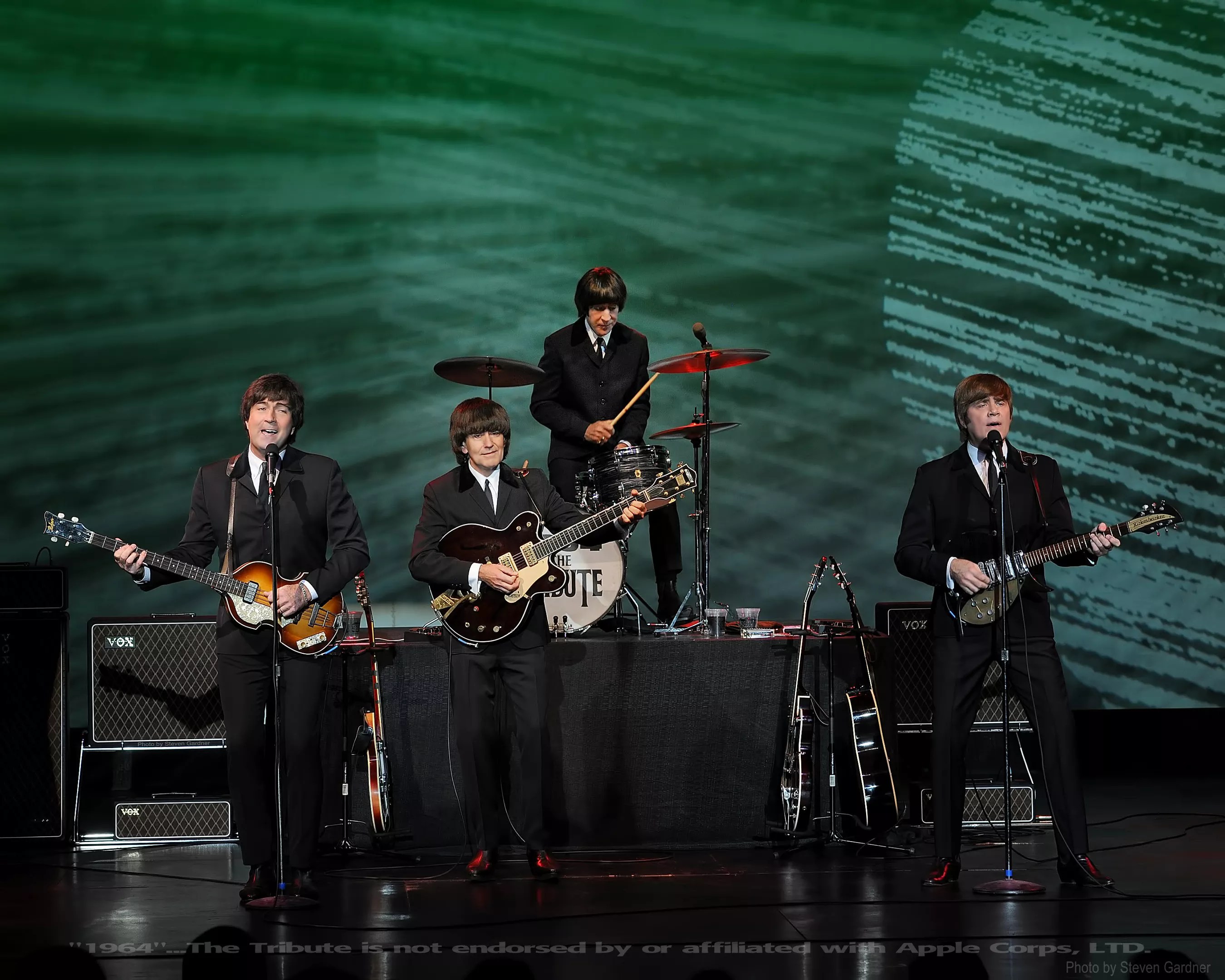

The four musicians – who are not from Liverpool, England, but Akron, Ohio – have spent decades honing their accents and musical repertoire into a near-perfect sonic replica of the Fab Four. That night at the Emerson Center, audiences members, if they squinted a little, might have thought they were at The Ed Sullivan Show.

The band’s founder, Mark Benson, who has played John Lennon since 1984, led the group to tribute celebrity by instituting a set of rules that takes musical imitation to an extreme. When 1964 plays live, for example, the band performs songs only from the Beatles’ 1962-1966 catalogue. That means no White Album, Abbey Road, or Let it Be. The Beatles, as any “insaniac” – what Benson calls obsessive fans such as himself – would know, toured for only four years, from 1962 to 1966. His band plays only songs from those years, because no one in history could have gone to a real Beatles show and heard anything else.

“They only concentrate on those touring years, so if you’re expecting to hear ‘Hey Jude,’ you’re not going to hear it,” says Steve Gardner, who does the band’s PR and gives off a friendly, used-car-salesman vibe (appropriately, because he touts an older, discounted product rather than a new, real thing). “What you’ll hear is a bit more energetic, a rock ‘n’ roll time, from when the Beatles still played before an audience – down to the banter in between the songs, down to the accents, the humor, the movements. They’re all as identical as can be achieved.”

Benson’s methodology stems from his background in guitars. He doesn’t specialize in your average Sam Ash acoustics but in restoring vintage instruments. He takes decrepit Rickenbackers and Les Pauls and reconstructs them, trying to re-create in the present day the exact sound they had when new. Benson sees tribute music, like restoration, as an art form, but one with a particular responsibility: to stay true to history, to meticulously reproduce sounds exactly as they originally occurred.

Benson’s own instrument, for example, is modeled after John Lennon’s guitar, a 1958 black and gold Rickenbacker. The two are identical down to the obscure detail, foreign even to many diehard fans.

“When John Lennon played in the really early years, the middle pickup on his guitar was inadvertently disconnected,” Gardner said. The pickup wasn’t working for the recording of famous songs like “All My Lovin’,” giving Lennon’s part a very particular sound. “Mark knows this. His guitar, although it has three pickups, the middle one is just the cover. There is actually no pickup underneath it.”

1964 the Tribute is so well known and so well respected that other acts admit to mimicking the band’s bits. Most often, younger groups steal jokes – the between-song banter 1964 members write themselves, in the style of the Beatles. But sometimes groups take techniques: They imitate 1964’s imitating. True insaniacs will know, for example, that although Ringo Starr played on a right-handed drum set, he was actually left-handed. He did what’s called “left-handed work,” meaning he always started his drum rolls with his left, not right, hand. It’s difficult to find a real lefty drummer, so 1964’s Ringo, who is a righty, learned to do left-handed work on his right-handed set. Eric James Smith, the Ringo of an act called Beatlemania Now, says that after seeing 1964 live, he reconsidered his whole approach to drumming.

“Their guy was leading with his left hand – single-stroke rolls, going from the floor tom to the high tom, just like Ringo did it,” Smith says. “I was blown away. I realized I had homework to do.” These days, Smith starts all of his rolls on the left.

Benson and his bandmates’ deeply researched, detail-oriented approach to their work undermines all assumptions about tribute music, a genre often dismissed as kitsch and déclassé. (The lameness of tribute acts was acknowledged even by audience members. None had an explanation – but it has something to do with nostalgia, a predominantly white baby-boomer fan base, and their tendency to mimic rock groups, groups whose allure hinges on sex appeal and an effortless cool, two things that anyone trying hard to achieve – as tribute bands inevitably do – probably won’t). 1964 the Tribute walks the implicit high-low boundary between music and imitation, between original and copy. The band elevates the form to a kind of historical reenactment, on par with performances of Greek theater on kathurni or baroque music on period instruments.

Steve Gardner

Gardner agrees. “Have you heard the phrase ‘the art and science of detection?'” he asks. Benson’s music, he explains, is kind of like that – both creative and precise, organic and linear. It’s science in its unwavering loyalty to research, and art in realizing that research convincingly. “When you see the body movements and you hear his voice when he’s talking, you begin to realize, Holy mackerel, a lot of work went into getting this character, this person, John Lennon, just right.”

Back at the Emerson Center, when the show came to a close, the audience trickled out and congregated by the merchandise table. There, 1964 offers T-shirts, knickknacks, and CDs, which sell surprisingly well considering that the songs should sound exactly like the originals.

On the subject of CD’s, a fan named Ernie Gallo, whose obsession nearly meets Benson’s (“I have a Beatles room in my house,” he said) offered an explanation. “I have every Beatles record. I have all the originals,” he said. “I have pristine 1964 magazines, and 1965 magazines. I have Beatles collectible cards at home, all five series, every edition, a Beatles drum set, all the 8-tracks. The CDs are just something else–they’re the same, but they’re different.”