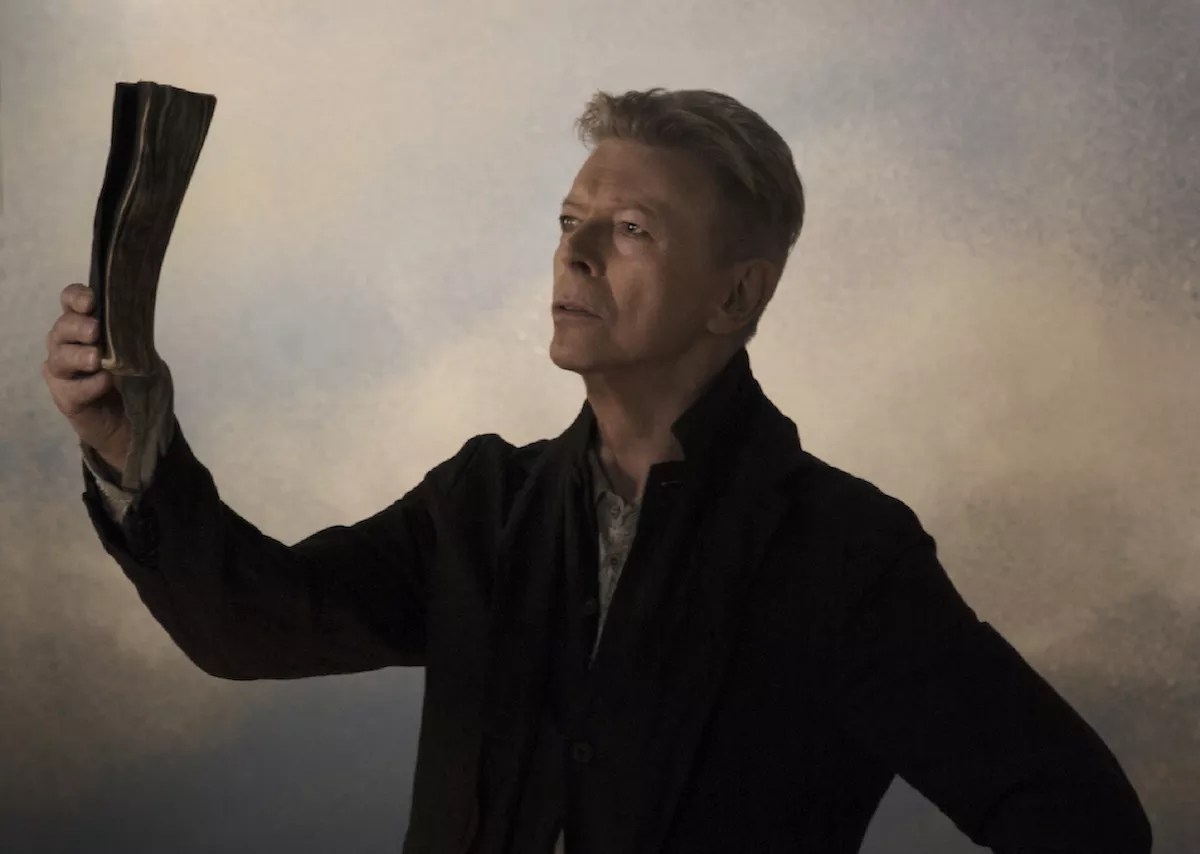

Photo by Jimmy King

Audio By Carbonatix

Though 2016 will be remembered as the year when a slew of iconic celebrities died, none will have gone out with as much style as David Bowie. Today marks a year since the British singer-songwriter seemed to have turned his death into an artistic statement. The seven-track album Blackstar was released on his 69th birthday, January 8, 2016. Then he died just two days later. It would turn out he had been fighting cancer for the past 18 months, a fact he had hidden from the public until his death was confirmed in a statement on his Facebook account. Tonight fans will gather at Churchill’s Pub for Bowie’s Blackstar Bash, where bands will celebrate the artist’s epic legacy.

Shortly after news of Bowie’s death broke last year, the record’s producer, Tony Visconti, a Bowie collaborator since 1969’s Space Oddity, wrote on his own Facebook page: “He made Blackstar for us, his parting gift.” The media and fans ran with the notion that Bowie made the album with the awareness that it would be his last. Although Visconti is incidentally correct, a new BBC documentary, David Bowie: The Last Five Years, calls into question whether Blackstar was a conscious effort by Bowie to create a final album before his mortal demise. The documentary’s director, Francis Whately, recently told the Guardian: “People are so desperate for Blackstar to be this parting gift that Bowie made for the world when he knew he was dying, but I think it’s simplistic to think that.”

Part of the hype of this legend came from the fact so few people knew Bowie was deathly ill. Even longtime collaborators were in the dark about Bowie’s cancer, including keyboardist Mike Garson, who had worked with Bowie on and off since 1972. Though he spoke of his shock about Bowie’s passing in several interviews not long after his friend died, Garson made an astute observation about death in Bowie’s music. “Mortality wasn’t something David discussed, but he sang about it a lot,” he told the Guardian.

One can trace Bowie’s obsession with death to his 1967 self-titled debut. The album ended with a stark yet humorous a cappella track, “Please, Mr. Gravedigger.” But genuine existential concern did not creep into Bowie’s music until 1971’s Hunky Dory, a profound album celebrating life with the birth of his son Duncan Jones (“Kooks”), the tension between a sense of self and the inevitability of time (“Changes”), and a very mortal concern for legacy in songs dedicated to artists such as Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol. Then there is “Quicksand,” a song about enlightenment inspired by both Nietzsche and Buddhism, a religion that sees death more as change than finality. In the chorus, Bowie sings, “Knowledge comes with death’s release.”

Bowie’s interest in death appears, to some degree, in almost every album he released. The theme is especially resonant in The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972) and even in his penultimate album, The Next Day (2013). In my Miami New Times review for the latter, his first album in ten years, I noted that it felt like Bowie had been reborn, exploring music again with a creative verve that portended he was only getting restarted.

To Bowie, death was not so much a morbid obsession as it was a factor in his ethos as an artist. He saw death as change. Almost simultaneous to the creation of Hunky Dory came Bowie’s definitive creation of an alter ego: Ziggy Stardust. Through this persona, he conceived the concept album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust. Before Ziggy could overshadow its author, however, Bowie retired him at the end of a nearly two-year world tour in London, on July 3, 1973, an act immortalized on film by D.A. Pennebaker.

At the end of the performance at the Hammersmith Odeon, before he performed “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” Bowie told the audience: “Not only is this the last show of the tour, but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do.” The crowd screamed in anguish as if Bowie had taken something beloved from them. This was a death. Only a few months later, Bowie released Pin-Ups, an album of British rock covers he deemed influential to his career as a musician. This was only one of several reboots that would steer him on a new creative path.

And the reboots kept coming. Soon after Pin-Ups, Bowie took on soul music with Young Americans (1975). In 1977, he moved to Berlin to create a pair of aggressively experimental records, Low and Heroes. In 1988, when Bowie found himself in a creative rut after the popular success of 1983’s Let’s Dance, he formed the band Tin Machine, in which he shared writing credits with his bandmates. During a tour of small theaters with Tin Machine, Bowie refused to play any of his solo music. After two albums, the band broke up in 1992. A year later, Bowie released two diverse solo albums, the soul/electronica hybrid Black Tie White Noise and The Buddha of Suburbia, a record that doubled as a soundtrack for a BBC miniseries of the same name, based on the book by Hanif Kureishi.

There is a pattern to be found in this sample of shifts in styles and approaches to music. With rebirth and renewal in creativity, there is also death and retirement. There’s resurrection via the kiln of the disposal of the old. Bowie always seriously considered what it took to change: He had to cut himself off from the past. Bowie was an ingenious creative who showed no preciousness for legacy. As a result, he became a legend. This leaves Blackstar as not only a final statement but also a testament to his ethos and, of course, a living, breathing piece of the artist for his admirers to cherish – not as an ending, but as a memento that carries that spirit of one of music’s most creative artists.

Bowie’s Blackstar Bash

With Sofilla, the Citadel, Similar Prisoners, and Kill Mama. Doors open at 8 p.m. Tuesday, January 10, at Churchill’s Pub, 5501 NE Second Ave., Miami. Ages 18 and up. Admission costs $5. Visit churchillspub.com.