Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/Photo by Lance Brewer

Audio By Carbonatix

Making the painting medium seem new and exciting in 2023 is hard. The medium has been declared dead and revived more than once in modern art history. The past decade or so has seen the rise and fall of “zombie formalism,” a wave of trendy, marketable, critically derided abstract painting. It was replaced with “zombie figuration” – the same thing, just this time with pictures showing recognizable people and things.

It’s hard to figure out how to put a twist on a medium that’s existed since the beginning of time, but for born-and-raised New York artist Avery Singer, that’s part of the appeal.

“[Painting] is constantly facing its own continual obsolescence,” she says. “I know that, and I paint with that knowledge in the backdrop of my mind.”

Singer’s solution is to embrace new technology. Two bodies of work are on display in “Avery Singer: Unity Bachelor,” the artist’s first large-scale museum show in the U.S. at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. The first uses models produced in SketchUp, a 3D modeling software, which Singer then puts on the canvas. “I make my drawings digitally, essentially, and I execute the work in airbrush,” she explains.

“[Painting] is constantly facing its own continual obsolescence,” Avery Singer says.

Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami photo

The second is even more cutting-edge, using commercial animation software and digital models usually reserved for special effects in movies and video games alongside industrial printing. Both processes attempt to respond to the massive shifts in visual communication and “the kind of industrialized, commercialized visual languages of today” that stem from new technological developments, Singer says. It’s a change she believes mirrors the modern art of 100 years ago.

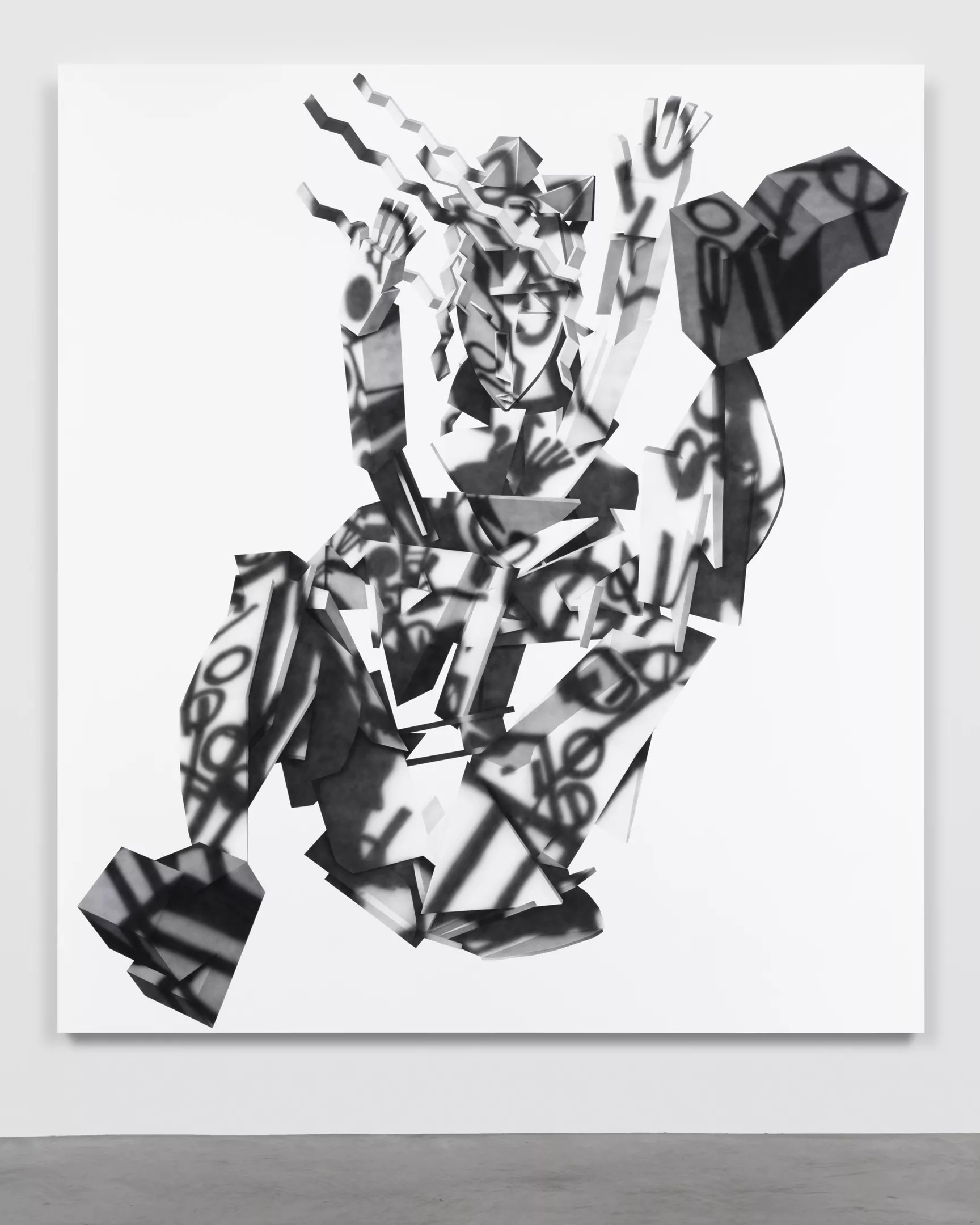

One painting in the show, Free Fall, explicitly alludes to these shifts. Featuring a 3D, humanoid avatar that appears to fall through a white void, the work references Marcel Duchamp’s epochal Nude Descending a Staircase, a significant breakthrough in European modernism’s experiments with depicting motion on canvas. The polygonal character covered with graffiti tags also resembles a Picasso cubist character given a three-dimensional form.

“That painting is about the introduction of photography as a way of capturing movement in space,” Singer says of the Duchamp work. Her painting is an attempt to do the same. “But I’m doing it in contemporary animation software.”

Avery Singer’s Free Fall

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/Photo by Lance Brewer

There’s also personal history here. Beyond formal concerns, much of the work on display in “Unity Bachelor” attempts to construct a world around her experiences as an art student in early 2000s New York City, dwelling on themes of addiction, recklessness, inebriation, and altered states of mind. The dark, graffiti-tagged canvases evoke the hazy anxiety of that period in the wake of 9/11, which Singer herself survived. The artist was just 14 when the World Trade Center towers were destroyed, and her family was forced to evacuate from their apartment near Ground Zero. Her mother, who worked in the World Trade Center building until June of 2001, likely would have died in the disaster if her company hadn’t shifted offices.

“My parents suddenly had to figure out what to do,” she recalls. “There was no possibility of going back.”

The family spent the first night in a projection booth at the Museum of Modern Art, where her father worked, and spent the later weeks staying where they could. Singer had to change schools; her old one was across the street from Ground Zero. And even when the family was finally allowed back to their apartment, they had to cross police checkpoints to get home and deal with shut-off utilities and fumes from the burning pile of rubble where the Twin Towers once were. Singer got used to difficult daily interactions with law enforcement and firefighters.

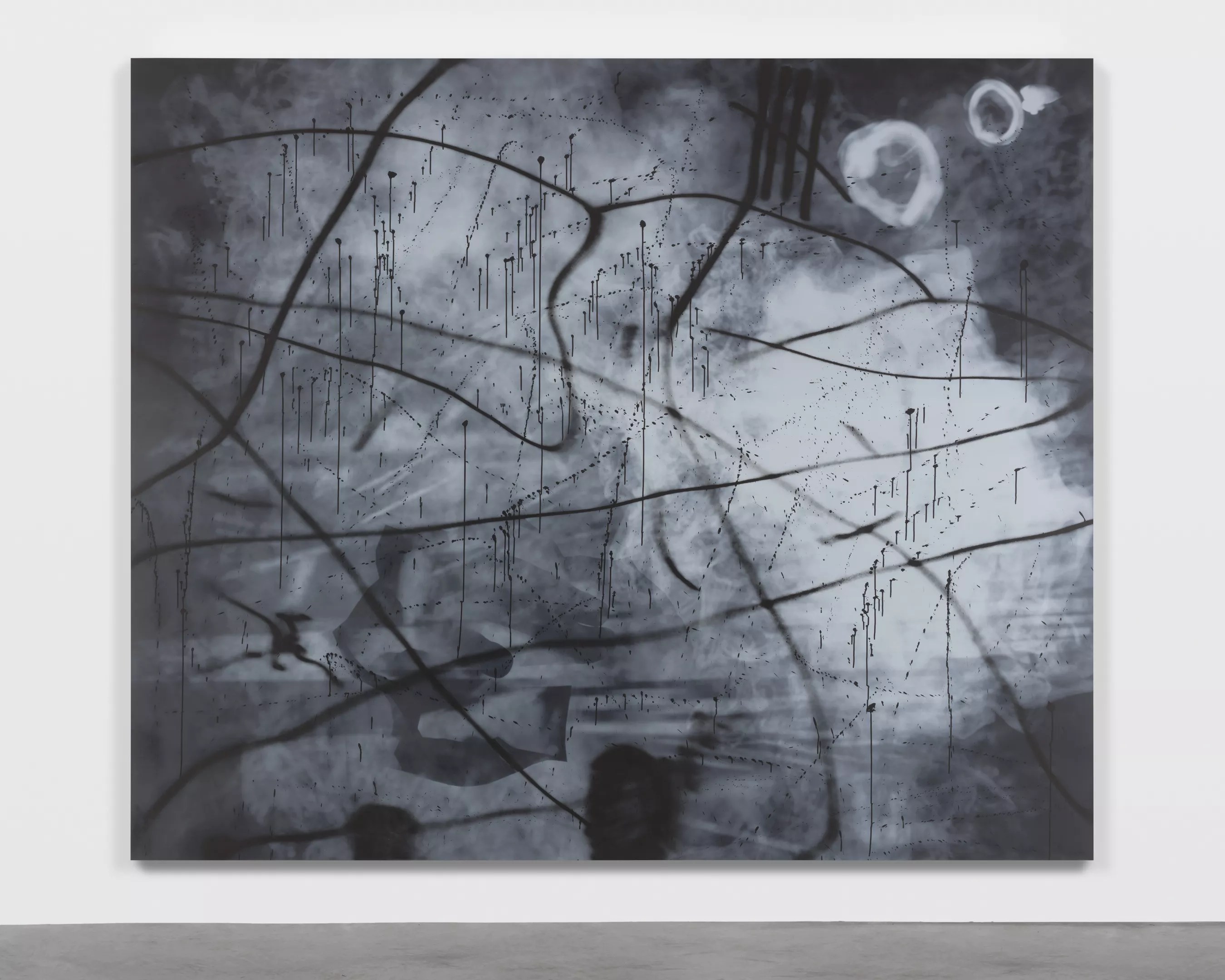

Avery Singer’s Black Out

Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth/Photo by Lance Brewer

“I’ve never seen so many grown men with tears in their eyes,” she remembers. “It was a really intense period for a long time.”

Singer’s experience highlights that, aside from the immediate politicization of 9/11 and its use in justifying the Bush Administration’s invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, it was an actual disaster that left a massive toll on those that survived. New York was never the same. “I grew up going to city hall, sitting on the steps. Now you can’t even get close to it,” Singer says, remarking on the “militarization” of the city.

Still a teenager, she would have panic attacks after hearing airplanes pass overhead and had to take medication that made her feel drunk all day. Black Out, a work in the show featuring her drunken art-student character, attempts to depict the sensation she felt while on the drugs, a sensation the artist believes she has yet to realize in her art fully.

“I haven’t quite figured out how to depict that.”

“Avery Singer: Unity Bachelor.” On view through October 15, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, 61 NE 41st St., Miami; 305-901-5272; icamiami.org. Admission is free. Wednesday through Sunday 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.