Photo by Zachary Balber

Audio By Carbonatix

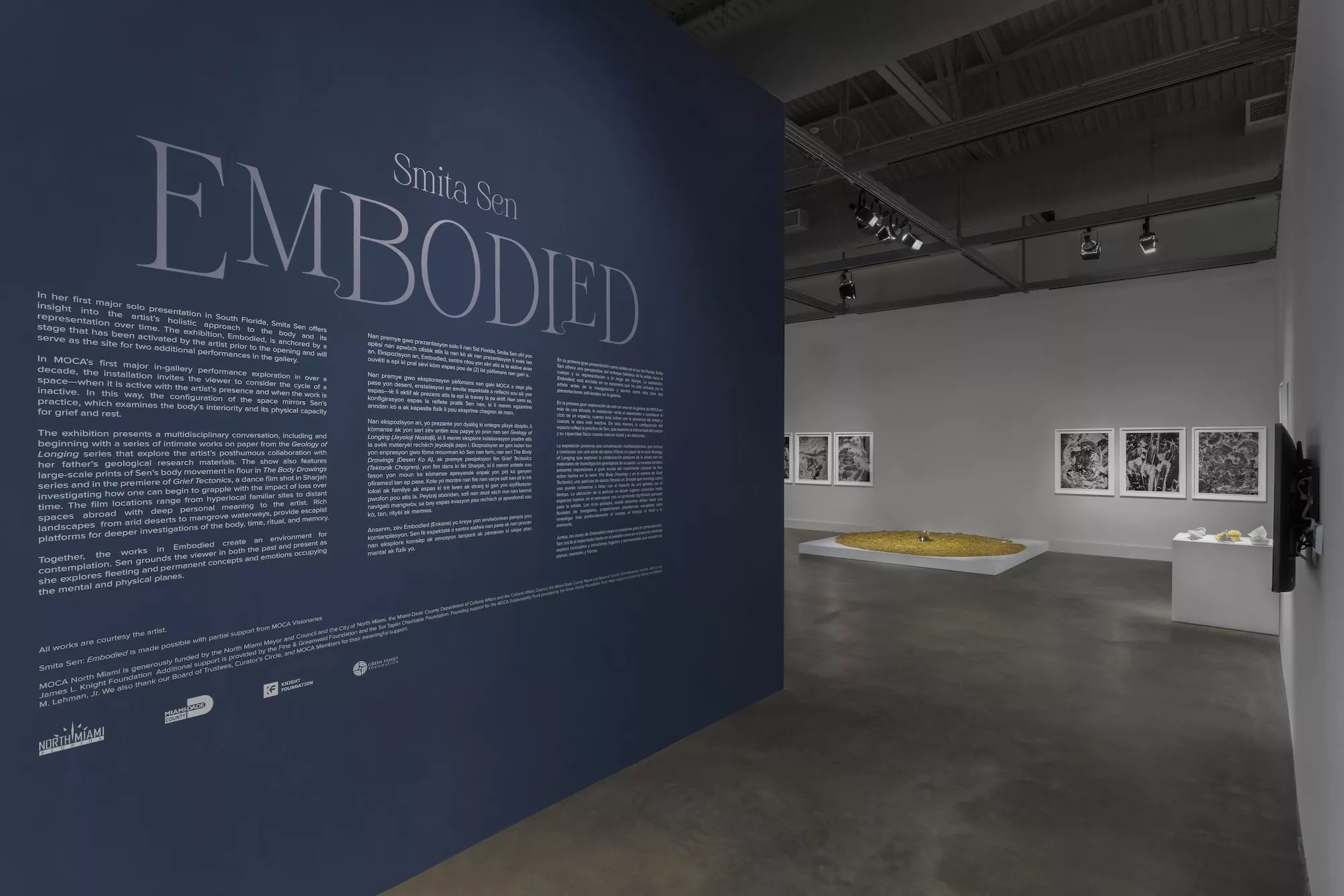

Earlier this month, the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, unveiled its latest exhibition as part of its winter programming. “Smita Sen: Embodied” lets the viewer witness some of Sen’s performances firsthand, reimagined within the museum’s walls through video recordings and live performances.

A Smita Sen experience is not your stereotypical, heady, white-box performance art that can be jarring and unrelatable for the average person, but rather an audience immersion with music, lighting, and sculptural installations with which performers – and occasionally audience members – will interact.

Because Sen’s early education was in dance, she carried much of that early discipline into her performance art.

“Dance was really my first craft. It was the first thing that I studied, built real professional competence in, and had a critical vocabulary for,” Sen tells New Times over Zoom. “That language – of learning how to understand the types of stage presences, the ways that we organize the stage, the ways in which we organize an audience – was presented to me very early, and it’s different from, but still connected to the language in which we discuss performance art, Fluxus, happenings, and how we interrogate the interruption of the day-to-day lived experience with performance.”

Viewers can see Sen gracefully move through physical and emotional pain throughout her performances. Much of her work has centered around her father’s death, her mourning, and the changes that happened between her and her family as they moved through the loss. Works like Rituals of Sacred Surrender express the guttural feeling of losing a loved one through movement. As she dances along to the violin of long-time collaborator and music therapist Trina Basu, Sen unfolds mourning as something beautiful, a hardship that is a part of life, a loss that people must carry with them in memory of the people they love.

Much of Smita Sen’s work has centered around her father’s death.

Photo by Zachary Balber

Many of the sculptural works in her practice, including Breathing Sideways, document the biomorphic, abstract experience of physical pain. Sen’s sculptures and drawings resemble body parts, like something you would remove in surgery. However, since they are 3D printed in resin with a sort of frosted glass finish, they also have a sleekness and glossiness that feels removed from an organic body. In a way, it is ironic that the sculptures deal with physical pain because, at times, they have been painful to make.

“I’ve always had a lot of joint pain. Even when I’m drawing or painting, I have to stop quite regularly,” Sen explains, adding that the computer made sculpture accessible, while something like ceramics, for example, proved too physically challenging without several breaks. “It was just me and my computer. And so it was this dialogue between myself and the machine as a way of understanding and visualizing and creating sculptures.”

This relationship with technology only grew stronger after an injury left her unable to walk properly for an extended period, leaving her with little other creative recourse while she healed. “Having the computer as a tool was really powerful; it was kind of like a revelation,” she says.

Sen is ethnically South Asian and expresses her identity in her work with a certain restraint and minimalistic style. Her culture informs her visual language, but instead of employing cultural motifs in their literal entirety, she reinvents them as subtle nods.

“It’s such a hard thing because I think there’s a really prescriptive idea of what South Asian art should look like and what reads as Indian,” she shares.

“I really believe that art can change people’s lives,” says Smita Sen.

Photo by Zachary Balber

The viewer who pays close attention can see her culture in the musicality with which she performs, her movements as she dances, and even the colors and textures of the objects she brings to her performance. In Grief Body Semiotics, for example, one can even see a video of someone dunking themselves into a body of water, a clear but nuanced reference to some of the traditions in South Asian religiosity. In bringing this part of herself into the work, she is also reinventing the aesthetic of these cultural motifs to fit into her process. She hopes that her family members and people from similar backgrounds see themselves in her work, but ultimately, it is meant to prompt broader conversations about pain, resilience, loss, and how people can navigate those things in their bodies.

“Smita Sen: Embodied” will not only feature several of the performances and sculptures referred to in this profile but also a new film by Sen, The Geology of Longing, where she travels to several places where her father studied throughout his life. When asked what she hopes to gain from this exhibition, Sen simply wishes for people to see the show for themselves. “I really believe that art can change people’s lives,” she says. “People can see the work, they can hear the work, they can experience the work, and I really try not to be high and mighty with the process. I try to make it open for folks to explore and understand.”

For viewers who may have never been interested in or seen performance work, this local artist, with a refreshingly open and humble demeanor, may be the person to change their minds.

“Smita Sen: Embodied.” On view through April 6, 2025, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, 770 NE 125th St., North Miami; 305-893-6211; mocanomi.org. Tickets cost $5 to $10; free for children under 12 and North Miami residents.