Photo from the Institute for Justice

Audio By Carbonatix

Chad Trausch is hoping his battle with the City of Miami’s permitting department will prevent it from strong-arming other homeowners into giving up a portion of their land just to renovate. That’s the “nightmare” Trausch, proud owner of a 1937-built home on NE 46th Street west of Biscayne Boulevard near the Design District, says he went through.

In March 2024, Trausch and his wife Stephanie sought a city permit to expand their home with a mother-in-law suite to accommodate their growing family and welcome his in-laws to South Florida. But the couple, along with their architects and attorneys, began to cry foul when the city asked them to give up about half of their front yard in exchange for the permit.

“Miami demanding half of my front yard in return for me building an addition in my backyard makes no sense,” Trausch tells New Times. “I’m just trying to help my family, but the city is using this as an excuse to take my property without compensation. It’s not fair, and it’s not right. If they can do this to me, they can try to do the same thing to anybody.”

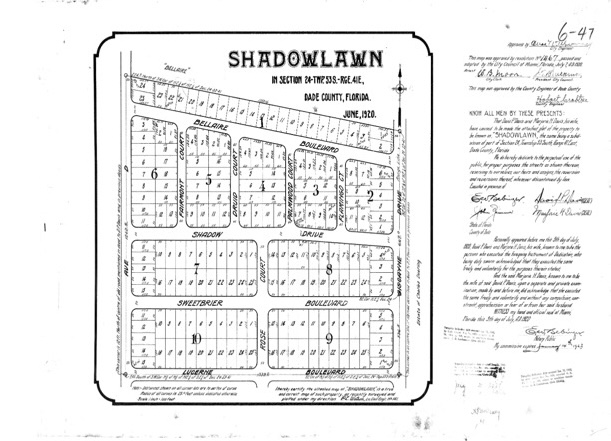

The city’s reasoning? A century-old planning map called for NE 46th Street, then known as Sweetbriar Boulevard, to be wider than it is currently. Trausch, a former Navy intelligence officer and Harvard University graduate, wouldn’t let the issue pass without a full investigation and became a veritable city code expert over months of studying, digging up the map that city planners cited.

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

A 100-year-old map is what the city used as justification for asking Chad Trausch to give up half of his front yard.

City of Miami archives

The city argued that it had the right to request that homeowners give up property in exchange for alterations that require changes to city street services. Despite Trausch and the architects’ assurances that the renovations wouldn’t do that, the city planning department wouldn’t budge. It held steadfast in the face of Trausch filing for an injunction as his own representation. The planning department only relented and granted the permit in November, after Trausch retained an attorney and informed the city of his intent to sue them. Trausch is backed by the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm dedicated to combating abuses of government power.

“It appears the city has unilaterally granted Chad’s waiver request — sixteen months after rejecting it; five months after filing a motion to dismiss Chad’s pro se lawsuit; and three weeks after learning that Chad obtained an attorney,” the lawsuit reads.

The city, however, argues it has fulfilled Trausch’s request, which renders the lawsuit moot, a spokesperson for the city attorney’s office confirmed to New Times.

“After the City gave Mr. Trausch exactly what he requested, Mr. Trausch’s lawyers decided to file an amended complaint demanding attorney’s fees and seeking media attention,” the city’s written statement reads. “We are confident the court will see this lawsuit for what it has become—a moot case with a plaintiff who suffered no injury.”

Trausch’s attorneys are seeking $1 in nominal damages for the due process violation and the abusive conditions he says he endured, as well as reimbursement of his attorney’s fees.

“The demand for land had nothing to do with the addition,” Institute for Justice attorney Suranjan Sen said in a press release. “The city didn’t seem to have any concerns with his building plan; it simply saw an opportunity to force Chad to give up part of his property.

“The right to prevent the government from unlawfully taking your property is a right recognized from the very start of this nation. The city of Miami cannot simply decide to take your property away because it wants it.”

Miami, like many cities in the U.S., requires homeowners to obtain permits before undertaking most construction projects or anything larger than your mom’s DIY bathroom decor revamps. However, in Miami, the government has used the permitting process to take land from residents without compensating them, Sen argues.

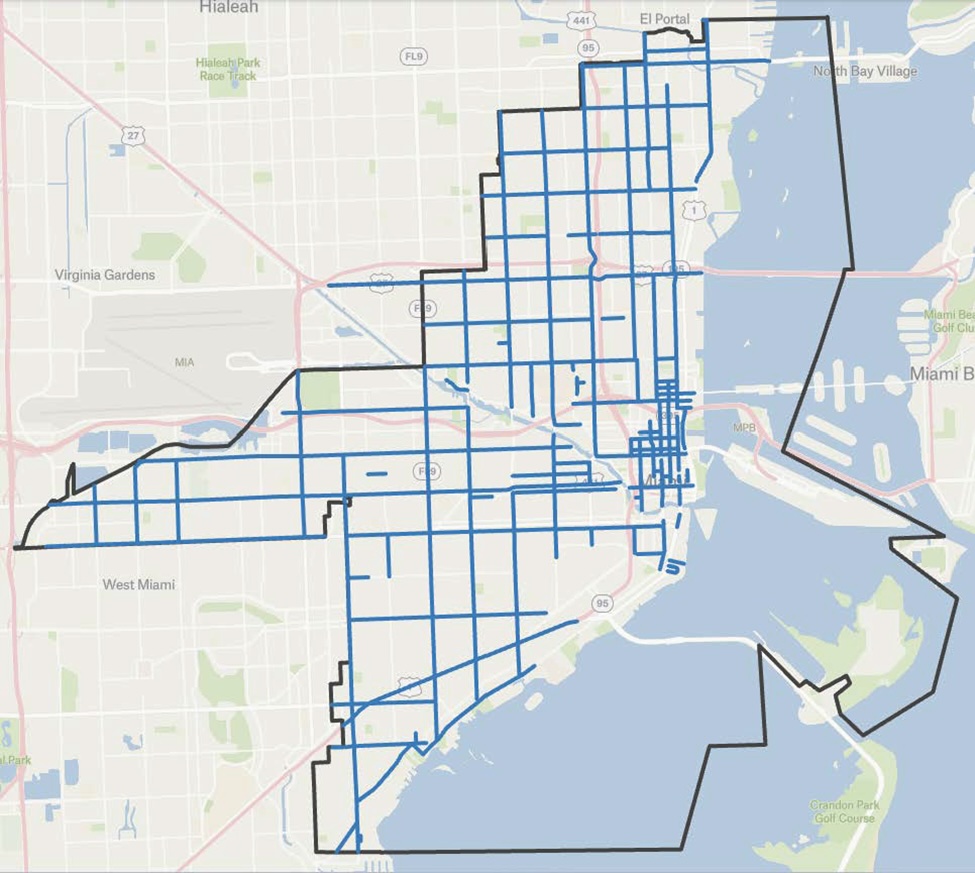

“The city has been doing this because it wants to bank the land to eventually widen roads at some point in the future,” he said in the statement. “As it currently stands, the Institute for Justice has been able to identify 66 streets with more than 1,000 houses at risk to this scheme.

In fact, Miami code outlines this exact scenario. Before the city issues a permit for new construction, an expansion, or a change of use, the public works director must determine that the project will impact city services or nearby streets. If so, the property owner must first give the city any portion of their land that falls within the city’s designated right-of-way for street use. Only after that land is dedicated can the project be approved, the code reads.

Institute for Justice graphic

“To make matters worse, the waiver granted to Chad was only for this particular addition,” Sen wrote. “The city still asserts it could demand Chad, or anyone else whose land they want, to turn over his land if he needed to go through the permitting process again.”

Institute for Justice attorneys argue the matter boils down to theft by extortion, writing in a press release, “People have a right to use their own property, so land use permitting conditions must be tailored to mitigating public harm from that use. But a city may not, under those conditions, require that the property owner do work unrelated to safety, like giving up half their front yard.

“Miami’s demand wasn’t related to Chad’s project; instead, the city attempted to obtain an unrelated benefit at Chad’s expense. That’s unconstitutional, and the city may not make such a demand.”