Photo by Shawn Macomber

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s a little after 11 a.m. at South Dade Senior High in Homestead and a class so unusual is in session it almost feels like a dream of an impossibly perfect school day: Celebrated Venezuelan violinist and three-time Latin Grammy Award nominee Daniela Padrón is putting on a virtuoso performance for the forty or so rapt students as her co-teacher for the day— the Universal Music-signed neo-soul pop chanteuse Manu Manzo, also a Latin Grammy nominee — steeples her hands at her forehead and sways in an appreciative cross-genre reverie.

What comes next, however, is just as remarkable: Padrón steers the conversation with the class not to one of the many moments of triumph from her career, but, rather, to a moment of challenge from her own teenage years. She was around sixteen years old. Classically trained since before the age of four, she was very comfortable in the world of notes and staff. “It’s like having a GPS,” Padrón tells the students. “You know exactly what you have to do, and you do it, and you sound amazing.” But then a friend invited her to jam at a rock band rehearsal. Suddenly, Padrón found herself without that scaffolding. “I was a classical soloist and pretty confident, but I had no clue what to do at that rehearsal because I did not have that paper map in front of me,” she says. “I was like, ‘This is not happening to me again. I need to learn to improvise.’” Slowly, but surely, she developed an improvisational flow — “like breathing” — that opened up new frontiers of creativity and set the stage for future success.

“I really just like to lead with my heart,” Manzo adds, as Padrón nods in agreement. “Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Just be honest and just go for whatever you’re feeling in the moment, because sometimes those things your mind worries might be absolutely ridiculous turn out to be the dopest things you do.”

A wave of epiphanies spread across the students’ faces in the room. This songwriting breakout session — part of a regional music career day bringing together the Los Angeles Grammy Museum’s Grammy in the Schools program, Florida music education heroes Young Musicians Unite, the Save the Music Foundation, and the Recording Academy Florida Chapter — is not a sermon delivered from on-high, relevant only for a select chosen few.

“I didn’t fully get what today was going to be like, but it turned out to be one of the most fun, exciting days ever,” sixteen-year-old junior Shaniyah Allen — a triple threat whose primary instrument is clarinet but who also plays trombone and serves as drum major of the marching band — tells New Times. “I learned so much about songwriting technique and new production technologies and the music business. The best part, though, was getting to ask the artists questions and see what they’re really about. I feel so inspired. Like, I can be an artist or a producer—I could see myself playing in a symphony; that’s my dream. After a day like today it really does feel like you can do anything.”

Only a few years ago this type of event would’ve been unlikely at best, an academic pipe — recorder? — dream at worst. But the remarkable rise of Young Musicians Unite (YMU), a non-profit which was founded in 2013 to revive music programs in underserved communities and now serves more than 12,000 students in grades 5-12 throughout Miami, is demonstrating just how much can be accomplished through intention, focus, and perseverance. (It’s not unlike practicing scales in this sense.)

The proof is in the numbers: Well over 80 percent of students participating in YMU programs reported “increased optimism for the future as well as more confidence to resist negative peer pressure.” Ninety-nine percent “maintained consistent attendance,” and 96 percent said they were “motivated to do better academically after taking music classes.” (Indeed, some principals are now scheduling challenging subjects right before or after music or art classes, when students are most engaged.) Further, teachers surveyed indicated 95 percent of YMU students “improved their ability to receive and apply criticism to their work,” demonstrating “increased social maturity and musicianship.”

Photo by Shawn Macomber

Which is to say, it’s about more than music: In fact, the Grammy Music in the Schools program calls its book on soft skills Careers Through Music not Careers in Music for a reason. “Success for us is not necessarily to have all these kids pursue a career in the arts,” Grammy Museum Vice President of Education and Community Engagement Arin Canbolat tells New Times, pointing out that improvisation, structuring songs, navigating interpersonal relationships, paring ideas down to lyrics and melodies are all applicable to more than just music. “It’s to have music impact them in a positive way, in a way that helps them go out and change the world in whatever way is best suited to them as individuals.”

This ethos is at the heart of why the Grammys want to be in partnership with Young Musicians Unite and Save the Music. “The coalition-building aspect of this work isn’t just important, it’s essential,” Canbolat says. “Otherwise, we’ll never reach a fraction of the kids who would benefit from these programs. A rising tide lifts all boats may be a cliché; it also happens to be true.”

This is literal music to the ears of YMU Chief Operating Officer Zachary Larmer, a music educator, yes, but also a Grammy-winning jazz musician who has worked with artists such as Pat Metheny, John Scofield, and the Steve Miller Band. “We want days like today to blow the doors off any perceived limitations these kids may believe they have,” he says. “Having organizations and artists of this caliber partner with us and show up with such commitment, energy, and generosity is just incredible.”

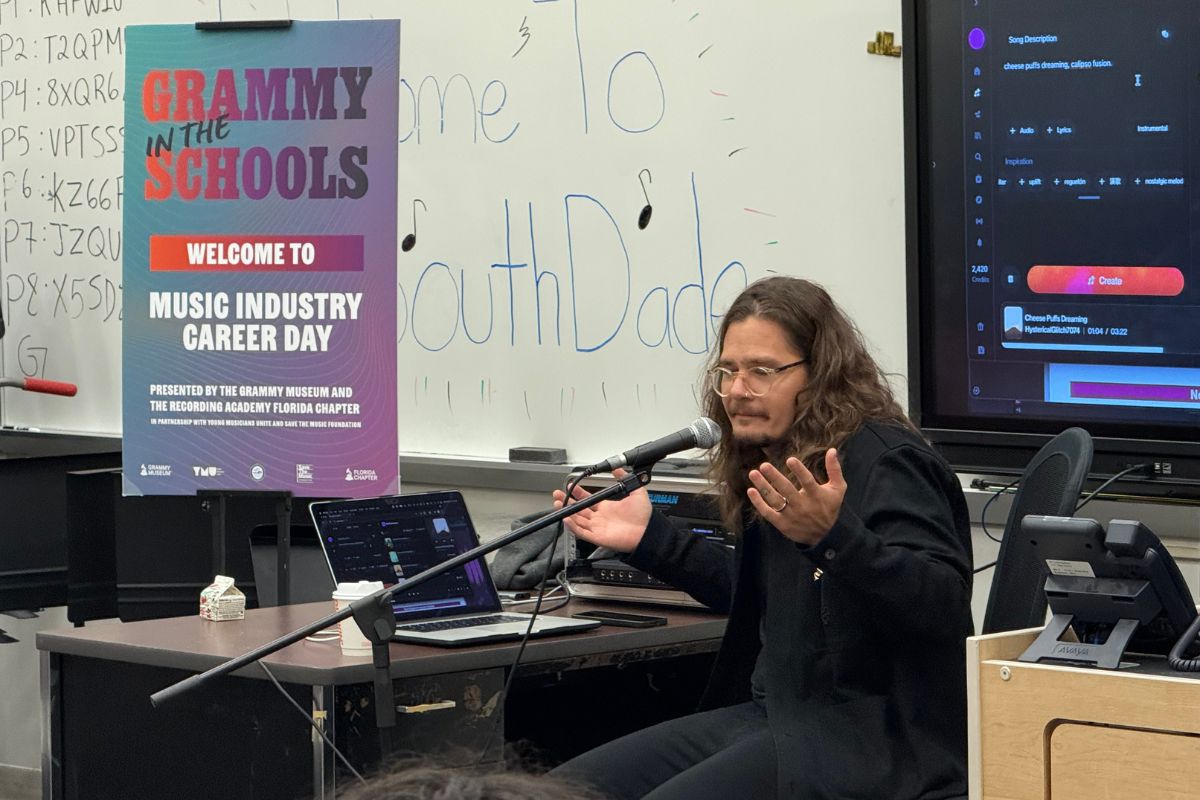

In another breakout room, this one geared toward music production, engineer and Latin Grammy winner Quaz DeVille is demonstrating how the accessible AI production app Suno can be used to generate and explore ideas, without replacing human creativity. Collectively, students and teachers workshop an ode to cheese puffs using the program to run it as a calypso jam, as a metal banger, and more. DeVille encourages the kids to think of early ideation like grocery shopping: “If you pick up bad ingredients, you’re probably going to end up with a result that you don’t love,” he says. “But if you choose delicious, organic, homegrown fresh ingredients, you will likely have a better outcome.” And, DeVille adds, it’s important to take their roles as chefs seriously. “I would advise you work on yourself as much as possible. Your reputation, your presentation are everything. Be punctual, be polite, be courteous, always.”

The kids are still singing hooks about cheese puffs as they head to the auditorium for a series of performances and presentations.

“The world will miss out on a lot of amazing talent if we don’t nurture it,” Kenny Cordova, who serves as the executive director of the Florida chapter of the Recording Academy, says as the seats fill up. “It’s right in our backyard, waiting for us to step up. Today is about showing these kids that we care, that amazing artists care, and that we’re all here to support and empower them.”