By day, they arrive on red double-deckers and luxury coaches, tourists from Tokyo, Toronto, and Teaneck who hit the streets of Little Havana hungry for a taste of Cuban Miami. Poking their heads into the shops and cafés on Calle Ocho, they linger for a cafecito, buy a cigar or two, or snap selfies with the Máximo Gómez Park domino players who stir the tiles with a rustling shekere sound before snapping them down on the tables.

At night, the locals take over. On weekends, especially during Viernes Culturales — a celebration of arts and culture held on Calle Ocho the last Friday of every month — the bars, restaurants, and art galleries are crowded with people of all ages testing the heat in a percolating South Florida hot spot that is neither South Beach nor Wynwood.

Some of Calle Ocho's appeal is the atmosphere. There are cigar factories, botanicas, fruterías, an iconic movie theater built in 1926, a monument to the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, and the house where federal agents pulled 6-year-old Elián González from a closet in 2000 and sent him back to his father in Cuba. There is history here.

Now more than ever, there is music. For the visitors who come day and night, that music — most of it Cuban — is a siren song. Fans line the block to get into the bar Ball & Chain and shimmy to salsa in the street in front of Cubaocho Museum & Performing Arts Center. They crowd into the doorway at La Esquina de la Fama, where violinist Ernesto D Marquez plays lyrical charanga that insists listeners get up and dance.

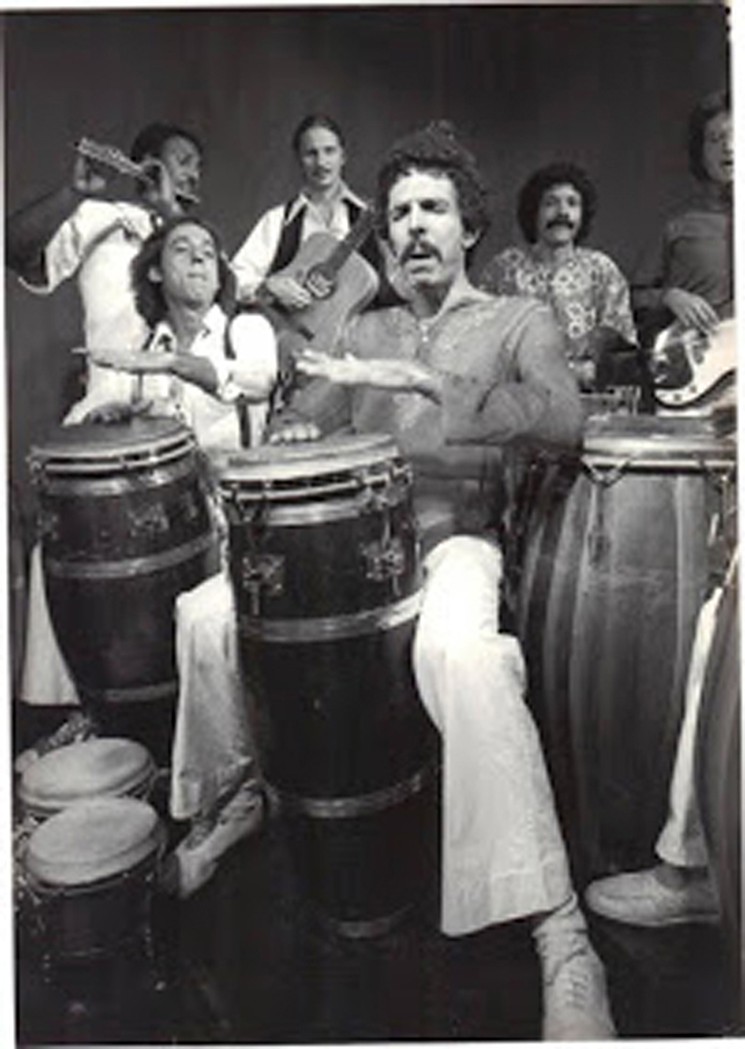

And depending upon the day of the week, the man providing the rhythm on congas, timbales, or bongos at these establishments might be Miguel Cruz, slight, gray-haired, a man of constant motion who is obviously every bit as delighted to be there as any of the hip-shakers in the audience.

"After the last crisis, I was afraid that I had lost it, maybe forever," says Cruz, who is again forming the callouses on palms and fingers that mark the hands of a lifelong percusionista. "People had given up on me, and I had given up on myself. I had lost the ability to be who I am. Then God took me by the hand."

"Leaving Cuba was not something I planned," he says. "It was a scary, but I wanted to go."

tweet this

The renaissance of Miguel Cruz parallels that of the neighborhood where he has spent much of his life, where he went to high school, drummed in impromptu descargas and at church dances, bought heroin and shot it up, lost his way.

Like Little Havana itself, Cruz has been down and counted out, remembered if at all as a faded musical link to a storied district that for years was under assault by crime, neglect, and urban flight. In the '70s and '80s, many Cubans moved up and out. Cruz himself left Little Havana for Los Angeles and South Beach to make his name.

Now, humbled but unbowed at age 70, Cruz is back, just as Little Havana is riding the crest of a cultural rebirth.

"He's an entertainer, an old-timer like Mongo Santamaría and Carlos 'Patato' Valdés," says Ezzio Chaviano, artistic director of Le Chat Noir, a downtown Miami jazz club where Cruz recently performed. "He's an institution."

But even institutions can perish, and Cruz came close.

"I've had people tell me they thought I had died," Cruz says. "And there were times when I thought I'd be better off dead."

In the '90s, Miguel Cruz was one of the biggest names on South Beach. He headlined at Mango's Tropical Café and packed the club five nights a week. Onstage above the bar, he fronted a tight, flashy group that poured out rumba, son, and mambo — Afro-Cuban rhythms honed in a long professional career playing with Mongo, Israel "Cachao" López, and Celia Cruz, as well as with his own band, Skins, in Los Angeles.

Known for his musical chops, Cruz was a hyperkinetic showman with a flamboyant theatricality that could move him to play the conga while tossing it over his head or lead a fevered conga line out onto Ocean Drive.

"He was like a psychedelic Desi Arnaz," Mango's owner David Wallack says. "He was Jimi Hendrix, he was Santería, crawling on the floor and still banging away on the drum. He carried us. He took the club from beer to Black Label, and we became internationally successful."

For Cruz, a working-class kid who was 13 years old when he came to Miami from Cuba, success in his adopted hometown was heady stuff.

Born in Havana's La Vibora neighborhood, Cruz was introduced to a drum at the age of 7, when his older brother Julio brought home a conga. Cruz had always been a drummer, pounding on the kitchen table or driving his parents crazy by using sticks to rap out rhythms on an overturned pot. He remembers being captivated by jazz drummer Cozy Cole's 1958 hit, "Topsy, Part II." That conga, he says, "became my favorite toy forever."

Cruz had only begun to find his way around the drum, however, when his parents sent him to Miami in Operation Pedro Pan, an exodus of more than 14,000 unaccompanied minors fleeing Marxist-Leninist indoctrination following the Cuban Revolution. "I was curious about the American way of life and the music, but leaving Cuba was not something I planned," he says. "It was scary, but I wanted to go."

He arrived in 1961 with a suitcase stuffed with 66 pounds of clothing, the maximum allowed, and $10 in his pocket. He stayed for a couple of weeks in a Miami shelter run by the Catholic Welfare Bureau and then went to live with the family of friends on SW Fourth Street in Little Havana.

A year later, Miguel's brother Julio, seven years older, arrived, and the two lived on their own in a Miami apartment. When their parents came in 1963, the family reunited in Allapattah.

Julio Cruz played music in Miami, but he also took up the cause of Alpha 66, a paramilitary exile group working to overthrow the Castro regime, at times via armed incursions on the island. Miguel was just 15 years old when Julio — who died in 2015 — left on one of those missions and asked his brother to fill in for him on a three-night gig at a club on NW 36th Street. That would be the downbeat for Cruz's professional career.

"After that gig, I knew I could do it," Cruz says. "I'm getting paid, and there was a chance of getting the girl. So I knew I wanted to do it."

Cruz attended Jackson High School and then transferred to Miami High. In the summer between his junior and senior years, he traveled to upstate New York with a Latin septet that had landed a gig at Grossinger's, the famed Borscht Belt resort in the Catskills. And there, at the age of 17, Cruz tried heroin for the first time.

"It seemed romantic — it had the mystique of the jazz musician," says Cruz, who was familiar with the literature of Kerouac and Burroughs, as well as the 1955 film The Man With the Golden Arm, in which Frank Sinatra played an addict and aspiring drummer who wins the love of Kim Novak. "It was a thing I thought musicians did."

Cruz says the heroin, supplied by an acquaintance, gave him a rush of pleasure he'd never known. "I just wanted to do it over and over again," he says. "Any pain, any anxiety was gone. And I didn't have the maturity to understand how it was also going to hurt."

After graduating from Miami High in 1967, Cruz continued to play music, often at Greynolds Park "love-ins" in North Miami Beach. Percussionist Dario Rosendo met Cruz there, and the two would remain friends for more than 50 years.

"We were a bunch of congueros, and Miguel was the leader of the pack," says Rosendo, a musicologist and retired Miami-Dade School Board auditor who also came from Cuba in Operation Pedro Pan. "He would outshine everybody."

As Cruz's musical development flourished, so too did his drug use. After another summer in the Catskills, Cruz came home and gigged while working a daytime delivery service job to come up with the $100 per day he needed to score heroin at a Little Havana drug hole near SW Eighth Street and 18th Avenue known as la esquina de pecado — the corner of sin.

Any stability in Cruz's life then came from his budding romance with a former high-school classmate, Milagros. But however strong Cruz's love was, drugs were stronger. He was arrested for possession several times in 1969, the same year he and Milagros married. He languished in the Dade County Jail for a year before being ordered into drug rehab.

"Jail was one of the worst experiences I ever had," Cruz says. "I was able to make it through without breaking down. I listened to the radio, wrote songs, and came out with a desire to start a new life."

When Cruz completed the rehab program in 1972, he landed a job at another Miami drug treatment clinic while attending classes at Miami-Dade Community College. He stayed clean, worked hard, and saved his money.

But music was his calling. In 1974, he, Milagros, and their infant son, Michael, moved to Los Angeles, where Cruz first gigged with the Latin-rock group Changó and then worked the "cuchifrito circuit," named for a kind of Puerto Rican soul food.

"Life was looking pretty good," Cruz says of those early days in California. Milagros handled the bookings, kept track of their son and the family income, and even went onstage to introduce her husband at performances.

At the same time, Cruz was becoming bored with Latin rock. He longed to find a truer musical identity. Something new was in the air.

As Cruz was prepping for change in Los Angeles, Little Havana was undergoing a transformation. By the mid-'70s, nearly 150,000 Cubans had left the neighborhood for homes in Westchester, Hialeah, and West Miami. But they couldn't forget their first home in the United States. "It was the spot where Cubans and non-Cubans went when they were in the mood for good Cuban food," Guillermo J. Grenier and Corinna J. Moebius write in A History of Little Havana, "and that Cuban feel."

In the '70s, Little Havana saw the completion of Domino Park; the establishment of social service agencies geared toward Cuban arrivals; the first Calle Ocho Festival, featuring Gloria Estefan and Miami Sound Machine; and a growing realization that this Spanish-speaking enclave could wield political clout.

But there were also clear signs of trouble ahead. In 1975, more than 30 bombings tied to anti-Castro extremists rattled Miami. They hit banks, TV stations, and the airport. Even Miami Police Department headquarters was attacked.

The onslaught highlighted the differences between rabid anti-Castro groups and those who favored improved relations with Cuba. This violence had a direct impact on Little Havana, Grenier and Moebius write, contributing "to the establishment of an urban setting of suspicion, uncertainty, and silencing."

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, Cruz became the leader of his own band. He formed Skins in 1978 to play his own compositions based on rhythms that obeyed the distinctive Afro-Cuban clave that rang in his head. Craving success on his own terms, he found it. Skins played the Hollywood Bowl, the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion at the Los Angeles Music Center, the Los Angeles Street Scene, and scores of other venues. He also began doing presentations at public schools and received plenty of press for both his music and his educational work.

"Miguel Cruz displays a sound with very special characteristics. It is not ordinary salsa we hear everywhere else," Record World magazine says. "It is a sound filled with incomparable creativity."

In 1980, the band released its first album, Miguel Cruz and Skins, and it was an immediate hit. Along with producing the singles "Canto Libre" and "Noche de Rumberos," it made the Latin pop charts.

Yo vi nacer lindo sol en la mañana

Y vi en tu ser la semilla del querer.

I saw the birth of the beautiful morning sun

And saw in your being the seed of love.

In 1975, more than 30 bombings tied to anti-Castro extremists rattled Miami.

tweet this

The critics weighed in. "Your Lp Skins is a masterpiece," music historian and Latin Beat Magazine senior editor Max Salazar wrote in a letter to Cruz. "To me it is the best example of genuine Afro-Cuban root music. It appears that you're on your way to becoming a legend like Arsenio [Rodríguez] and Chano [Pozo]."

Cruz released a second album, "Músico, Poeta y Loco," in 1982. Critic Darcy Diamond of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner wrote the recording was "wild with emotional inflections — both rhythmic and melodic patterns jump off the vinyl con energía, with spunk." Diamond went on to say that a witness to the band's stage show, saturated with percussion, "might swear that Cruz and company, in their trace-like fervor, were high priests of a joyous, melodic religious awakening."

Soon Cruz was recording with Stephen Stills, Linda Ronstadt, and Paquito D'Rivera. He played percussion on Ry Cooder's movie soundtracks Brewster's Millions, Crossroads, and Blue City in 1985 and 1986.

But in the late 1980s, he also began using again — and lying to himself about where he was headed. He would use only on weekends. He would only snort drugs, not shoot up. He would not neglect his family, which by then included a daughter, Mia.

The toll was wrenching. With Cruz unable to function, the calls for work stopped coming, the gigs disappeared, the band split up. The marriage foundered. "She tried, but it became impossible," Cruz says of Milagros' efforts to keep the family together.

On his own, Cruz bounced around, living in rented rooms and with friends until 1990, when a nephew arrived and helped him get home to Miami and into a detox program.

Once cleaned up, Cruz landed a job making early-morning deliveries of vegetables on a route that took him to Miami Beach. It led to a fateful meeting with Wallack at Mango's.

Mango's opened in 1991. "We were putting on rock, reggae, and country, more of a sports bar kind of thing, and we were struggling," Wallack recalls. "And then one day, Miguel wandered in and said, 'I'll rock the house.'"

Wallack had heard boasts like that before.

"Talk is talk, but when they get up onstage, you see what they've got," Wallack says. "Miguel was a singer and a percussionist; he had the smile and personality and the confidence...When my girls jumped on the bar and started dancing, I knew. I never asked them to do that. He's a star."

Dayami Estevill met Miguel Cruz in 1991, when she was not long out of Miami's New World School of the Arts and still in her teens. Cuban-American, born and raised in Miami, and trained as a vocalist, Estevill began going to see Cruz's show after finishing her own gig at the Fontainebleau Miami Beach.

Months after their first meeting, she joined Cruz onstage to sing a soulful rendition of the standard "My Romance" to a bolero rhythm. They shared a passion for music, a sense of humor, and, despite a 24-year age gap, a mutual attraction that led to their romance.

Cruz brought her into the band, and in 1995 — when she was 23 and he was 47 — they married.

"He's a natural-born musician," Estevill says. "He just has an innate ability to make people jump and dance."

After several years, the Mango's gig had run its course. Cruz and Estevill moved on as a duo, performing at clubs, business conventions, and private parties. They each worked solo gigs as well.

In 2001, Cruz joined Cachao, Alfredo "Chocolate" Armenteros, Patato Valdés, and other Latin music giants to record Cuban Masters, Los Originales, which was nominated for a Grammy.

Early in the new century, Cruz had also begun using heroin again. The gigs went away, money was scarce, the bonds of marriage frayed. "Addiction disguises itself as a nice guy," he says. "There's always a good reason to get high. But there comes a time when it beats you up real bad."

Cruz and Estevill split up about five years ago. "I still love him, and always will," she says. "But I had to get out."

Cruz found a room and paid the rent by teaching percussion, passing out flyers, or twirling a sign for a chain of barbershops. Some days, he would take a small conga and a boombox with him, lash the barbershop sign to a power pole, and play and sing to pass the time. He got recognized: "Hey, did you used to be Miguel Cruz at Mango's?"

"It didn't feel good, not at all," Cruz says. "So I was completely detached. I had lost my camino, my way."

For much of the '80s and '90s, Little Havana also seemed a little lost. It saw more violence related to El Exilio causes and had an oppressive air of political correctness that influenced what music could be heard and what art could be displayed. With an influx of new residents from Cuba after the Mariel exodus and others fleeing political turmoil in Central America, the population of the area grew denser, poorer.

Gangs sprang up, and a 1982 City of Miami report warned that the area was in danger of becoming the county's first Hispanic slum.

Then, with the new millennium, came a turnaround, ignited in part by the optimism of second-generation Cubans unencumbered by the political baggage of the past. Investors arrived to spark gentrification. Viernes Culturales began in 2000. Art galleries, restaurants, and souvenir shops opened, and giant rooster sculptures appeared on sidewalks. There was a growing perception that Little Havana was cool.

"I still love him and always will," she says. "But I had to get out."

tweet this

Music could always be found in Little Havana, chiefly at Centro Vasco and Café Nostalgia, both now gone. But Hoy Como Ayer, which opened in 2000 in the old Café Nostalgia space, hosts performances by musicians such as Willy Chirino, Albita, and Septeto Nacional. The longevity of the club, at 2212 SW Eighth St., is a testament to the appetite for Cuban music in Miami.

When Bill Fuller and his partners in the Barlington Group reopened Ball & Chain in September 2014, they decided to test the strength of that musical appetite. The club had opened in 1935 and then become both prominent and notorious before closing decades later.

Fuller and company planned to not only present late-night acts on the open-air Pineapple Stage out back, but also hire bands such as Pepe Montes & His Conjunto to play afternoons just inside the club's open doors. From the beginning, the music was seductive, often causing pedestrian traffic jams on the sidewalk.

"Live music is an investment, and you have to be willing to make that investment for the long term," says Fuller, whose club offers 80 hours of live performance a week and has been a catalyst for other clubs and restaurants in the area.

"Nothing would make me happier than to see 20 venues for live music here over the next few years," he says. He envisions East Little Havana as a mecca for Latin music just as New Orleans' French Quarter is for jazz.

Seven years before Ball & Chain reopened, Roberto Ramos and his wife, Yeney Fariñas Ramos, also took a gamble on Little Havana with Cubaocho, an eclectic art museum and performing arts space at 1465 SW Eighth St. Only a few bars and restaurants were thriving in the area then, and the callejón across the street was a neighborhood hangout, Fariñas Ramos says. "Tourists would come by, but there was really nothing to see, nothing for them," she says.

The couple set out to change that by displaying much of Ramos' extensive art collection, founded on seven works hidden in the wooden sides of a small boat on which he and his brother fled Cuba in 1992. In addition to art, Cubaocho offers a research library, two bars, and a staggering menu of rums.

And, of course, there is live music. "For Cubans, everything is music," Ramos says. Among those who have appeared on Cubaocho's stage are Giovanni Hidalgo, Cándido Camero, and Orquesta Aragón.

In 2015, a year after Ball & Chain opened, Cruz was making $10 an hour passing out car insurance flyers on the sidewalk along Bird Road near La Carreta when a black SUV came out of a parking lot and hit him with an impact that sent him flying into the road. He was left with a fractured hip.

Cruz was taken to the hospital, where doctors declined to do much except prescribe morphine. Months earlier, he had fallen off a motor scooter and suffered a hairline break that had begun to mend, and surgeons thought it best to leave the hip alone, Cruz says.

Discharged, he went home to half of a dilapidated trailer in a low-rent park near Calle Ocho and SW 37th Avenue. Barely able to move, he had no money and no medical insurance. He relied on friends to bring him food.

"This situation was very bad," his longtime friend Rosendo says. "I didn't think he was going to make it."

Facing eviction from his $500-a-month hovel, Cruz called his son, Michael, to ask for help moving. Michael, himself a recovering addict, showed up one day in late summer and told his father plans had changed.

"Let's go. I'm taking you to rehab," Michael says he told his dad.

Cruz resisted. "He said, 'That's not the help I want,'" Michael recalls.

"Well, that's the help you're getting," the son replied. "You cannot live like this anymore."

Soon Cruz was in drug treatment in Homestead.

"I felt like I was pulling him out of death," says Michael, age 43, who lives with his wife and son in Oregon and is 15 years clean.

Cruz had gone through detox and rehab programs before, but this time, he says, it felt different. "I was in bed, not able to walk, crippled, with nobody around," he recalls, "because at some point people give up. And I had given up on myself."

While in the program, Cruz qualified for a small social security pension and Medicaid. After settling a $29,000 debt owed to the Internal Revenue Service, he also began receiving music royalties that had been garnished for years.

After completing the program, he returned to the hospital, where surgeons inserted a titanium replacement for his right hip.

In his eighth decade, Miguel Cruz is not the acrobatic performer he once was. "I used to do a Michael Jackson-style split, dance around, and pick up a handkerchief with my teeth," he says. "I don't do that anymore."

But while playing the conga, bongos, or timbales, he still uses the handkerchief with dramatic flair when the spirit of the orisha Changó — the patron of drumming and dance — moves him to get up and break into rumba.

"Miguel is so important to preserving the legacy of Cuban music in Miami because he is so talented," says historian and music collector Eloy Cepero, a retired banker. "And he has that charisma."

Cuban-American actor and percussionist Andy Garcia has known Cruz since the late '70s and considers him a mentor. "He is an extraordinary percussionist, especially with all the Afro-Cuban dynamics, and a force of nature onstage," he says.

Garcia, who lives in Los Angeles, says he plans to be in Miami later this month and hopes to jam with Cruz. "I'm eager to see him, hug him, and play with him," Garcia says. "We all love Miguel."

These days, Cruz lives in an efficiency apartment a mile and a half south of the heart of Calle Ocho. He has no car, so he walks there and back as he reflects on the world he's passing through.

"I feel like it's my neighborhood, marked with my footprints," he says. "I used to live over there; I had a friend who worked there; there's la esquina de pecado, the place I had to go to every day.

"I am like a tourist here now, enjoying the panorama of things," he says. "I am not in a hurry to get to the next place. I am enjoying the journey."

Cruz and Little Havana may have found each other at the right time. Both have struggled; both seem to be on the rise. If there is a rhythm to this shared renaissance, it is a Cuban tumbao.

On March 23, Miguel Cruz is scheduled to make his first appearance at Cubaocho with his band Sugarcane in what promises to be a milestone in his comeback. "Things are happening that I never could have expected two years ago," he says. "Now my job is to create that joy and put on a tight show with music that sounds the way it sounds in my head."

Many people are pulling for him. "He was once the king of South Beach," Rosendo says. "I think he's going to be the king of Calle Ocho."

Adds his son, Michael: "To see where he is now, it really is a miracle."