It seems as though at one time or another every law-enforcement agency in Miami has investigated some aspect of this case, from county police to the FBI, the State Attorney's Office, and the U.S. Attorney's Office. A river of paper winds from Miami to West Palm Beach to Washington, D.C.

Now, twelve years after Miami's own "trial of the century," the Miami-Dade State Attorney's Office is taking a closer look at a small yet chilling tributary. The new probe focuses on an alleged incident in early 1987, when three River Cops and two accomplices are said to have plotted to murder a man who was preparing to testify against one of them in another case.

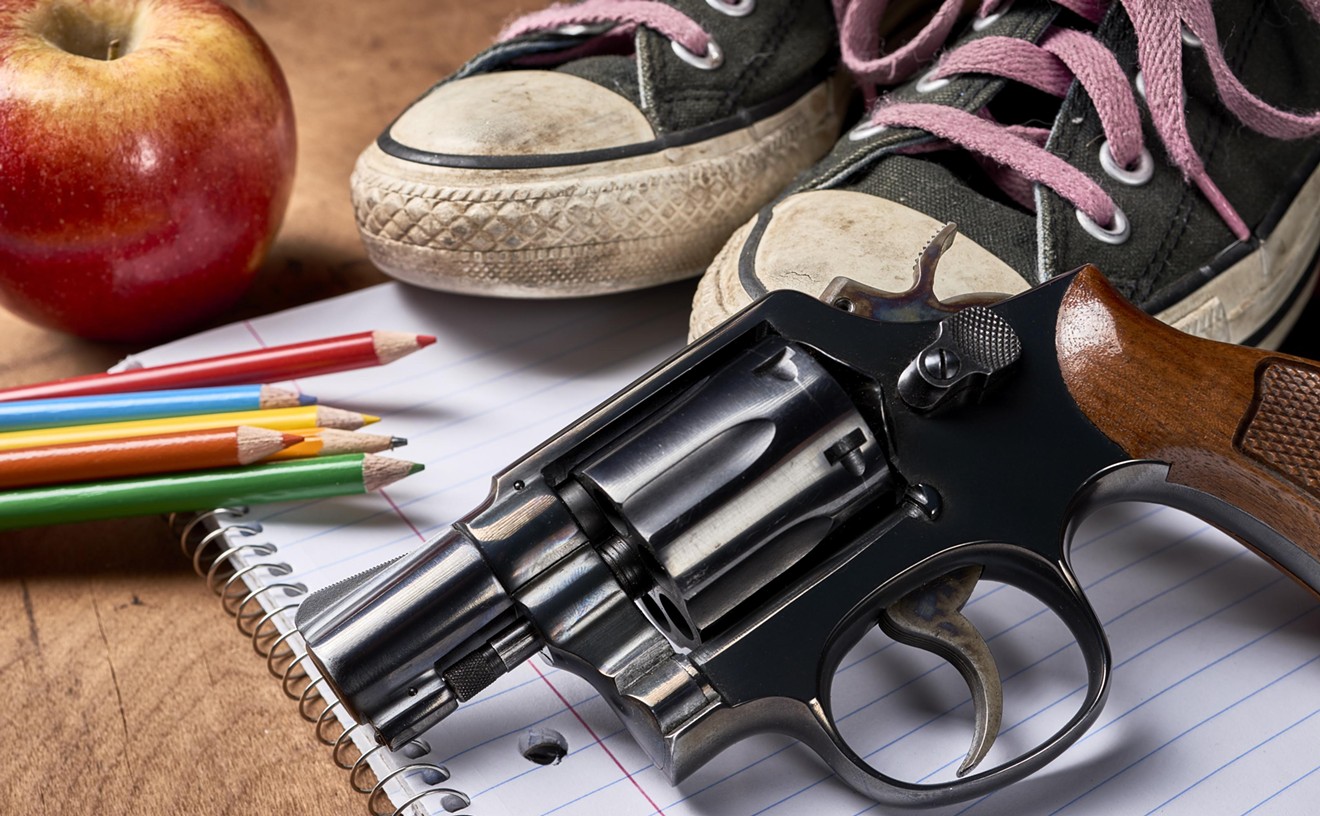

In a 1987 pretrial statement to police, River Cop Rodolfo "Rudy" Arias turned state's evidence. In addition to flipping on fellow criminals in his department, Arias also admitted that he, two other River Cops, a civilian, and a Dade County school district police officer waited outside the house of a witness named Dick Fiallo one night in early 1987, planning to kill Fiallo when he returned home.

According to this statement, the school cop's name was José F. "Pepe" Gonzalez. In 1987 he was a patrol officer. Today he is an assistant chief of the Miami-Dade Public Schools Police.

The State Attorney's Office is investigating, but has not charged Gonzalez. The assistant chief himself declined to comment for this story. His attorney, Glenn Kritzer, says his client willingly spoke with investigators last week. "Either Mr. Arias was confused, or he's lying," Kritzer says. "The statement is incorrect, inaccurate, and untruthful." But Kritzer acknowledges that Gonzalez was once good friends with one of the most notorious of the River Cops, Osvaldo Coello.

In July 1985 six men who were offloading drugs at the Jones Boat Yard on the Miami River panicked at the sight of police and jumped off their boat, the Mary C. Three of them drowned. This incident gave rise to both the investigation and the defendants' nickname.

When the SAO filed charges against seven City of Miami officers in December 1985, Gonzalez stood up on behalf of Coello. At a January 1986 bond hearing, Gonzalez described himself as a "good friend" of Coello. "I've known Osvaldo Coello for approximately six or seven years," he testified. "We entered the [police] academy together." (At that time Gonzalez had been a school cop for a little more than four years.)

Gonzalez's father, José R. Gonzalez, wrote a $7500 check to bond Coello out of jail. Other collateral included Coello's own house, the younger Gonzalez's house, and a 1985 Corvette that the elder Gonzalez owned. In his testimony Officer Gonzalez admitted that Coello drove the car "on occasion."

Because the case involved so many defendants, the lengthy discovery and deposition process in state court could have bogged things down for years. So in June 1986, state prosecutors took the case to a federal judge. The first trial ended in a hung jury in January 1987. While prosecutors were preparing another attempt, they caught a major break: Rudy Arias, one of the defendants, agreed to become a prosecution witness.

Then-Metro-Dade Police Det. Alex Alvarez, the lead investigator in the case, interviewed Arias in May 1987. The resulting 122-page document, called a debriefing, was a gold mine of evidence against the other six River Cops. It also helped lead to the indictment of six more City of Miami officers.

According to Arias, Pepe Gonzalez's friendship with Osvaldo Coello went far deeper than helping to bail a pal out of jail. As Arias describes it, Gonzalez was willing to commit murder to aid his corrupt buddy.

The following description of the incident is drawn from Arias's debriefing, which is not a sworn document but part of a closed criminal investigation. New Times obtained it in response to a request made under Florida's public records law.

Sometime between early February and early May 1987, Arias and Coello met at Sergio's Cafeteria in Southwest Dade. Coello said he had been involved in several robberies. He was worried because one of his cohorts, Dick Fiallo, "was a witness against all of them in the home-invasion case." Coello requested Arias's help to kill Fiallo. The pair met with a civilian thug named Pablo "Tatico" Martinez, who also was part of the robbery gang, and cased Fiallo's house; they later secured a pair of Mac 10 machine guns for the job.

"The following day Coello invited Arias to a party at the residence of Metro-Dade school board officer José 'Pepe' Gonzalez," the debriefing reads. Also present was another River Cops defendant, Arturo de la Vega. "At the conclusion of the party, de la Vega, José Gonzalez, Coello, and Martinez decided that they were going to kill Dick Fiallo that evening. The group agreed to meet at a shopping center.

"De la Vega was in his red [Nissan] 200SX along with José Gonzalez, who was armed with a shotgun, which he loaded with birdshot and was in the back seat of de la Vega's vehicle.... Osvaldo Coello and Pablo Martinez were in Arias' [Nissan] 280ZX."

They drove by Fiallo's house and saw that nobody was home. "At which time they met up with de la Vega and Gonzalez, who were surveilling the location approximately one block away.... They told de la Vega and Gonzalez to stay there.... They were going to check the discotheques to see if they [could] find Fiallo."

Arias, Coello, and Martinez drove to Casanova's in Hialeah, then to another disco at the old Bakery Centre in South Miami (now the site of the Shops at Sunset), but saw no sign of Fiallo. As they returned to their quarry's house, another car approached with high beams on; Coello and Martinez panicked, thinking it was cops investigating the home invasions, so they fled "at a high rate of speed," drove around trying to lose the car, then went to a friend's house and switched the 280ZX for a pickup truck. De la Vega then beeped Arias; it turned out he had been driving the car with the high beams.

The five then returned to Fiallo's house with a new plan: "Coello and Martinez were in the flatbed of the pickup truck, armed with Mac 10 machine guns, and the plan was to wait for Fiallo to arrive and that they would drive by his residence; as they exited the vehicle, Coello and Martinez would stand up in the bed of the truck and shoot him down with the Mach [sic] 10 machine guns."

After an hour and a half passed, they revised the scheme: "Coello and Martinez ... decided that they would hide in the bushes of Fiallo's residence and wait for him to arrive and shoot him as he [came] out of the car.... At approximately 5:00 a.m., Martinez and Coello returned to the truck and stated they got tired of waiting around the area and that a dog started barking at them from Fiallo's house.... They met with de la Vega and advised [him] they were finished for the night, at which time de la Vega took Gonzalez home."

Gonzalez's attorney Glenn Kritzer says this entire story is hogwash -- except for the party. "There was a time when José had a Christmas party and he invited Coello," Kritzer says, noting that Arias had described the party as having been some months after the holiday season. "At that same party, Coello apparently invited Arias. The rest [of Arias's story] is fiction. De la Vega and Martinez weren't there; [Gonzalez] never left the house; he didn't even own a shotgun."

Where are they now? Osvaldo Coello was sentenced to 35 years in the River Cops case in February 1988 and is still in federal prison. Pablo "Tatico" Martinez was arrested in 1989 on federal drug trafficking charges not directly related to the River Cops case. He was convicted shortly thereafter and currently is serving a 24-year prison sentence. Dick Fiallo did indeed testify in the home-invasion case; he is now a free man. Arturo de la Vega got 30 years but has been paroled. Arias served three and a half years in prison, then spent some time in the witness-protection program before returning to Miami in the mid-Nineties. Since then he has worked as a chef at several Cuban restaurants. New Times was unable to locate Arias for comment on this story. The lead River Cops investigator, Alex Alvarez, now a private attorney, declined to comment.

And José Gonzalez? The only blemishes on his eighteen-plus-year record as a school board cop: His department's internal-affairs unit has twice investigated him for alleged misconduct and twice cleared him of serious violations, though he did receive administrative rebukes for minor breaches of department policies in each of those instances. He became an assistant chief in January 1997. He is one of two officers of that rank who report to the chief of police.

The 37-year-old Gonzalez has never been charged in connection with the alleged attempt on Dick Fiallo's life. "We're looking into it now," says Assistant State Attorney Trudy Novicki, who prosecuted the original River Cops case. "I don't have a good answer for why it took us thirteen years to investigate this, but the honest answer is that the information was part of large investigation that eventually went over to the U.S. Attorney's Office." Another prosecutor who handled the River Cops case, Russell Killinger, did not return several phone calls from New Times seeking comment. Novicki says her office revived the inquiry about a year ago, when "someone brought it to our attention."

Glenn Kritzer says his client believes Commander Vivian H. Monroe, the former chief of school police and Gonzalez's greatest political enemy within the department, made the call. (One possible piece of evidence for Kritzer's allegation: During the reporting of a recent New Times cover story, "Cop Out," [March 9], which detailed questionable conduct by Monroe, an anonymous letter circulated among school officials and the media. It accused several high-ranking cops of malfeasance and included the fact that an assistant chief was under investigation for his connection to the Miami River Cops case.) Monroe was out of town and could not be reached for comment.

Novicki would not say when the probe might conclude. Even after all these years, there isn't any particular hurry. "[Arias] described an attempted first-degree murder with a firearm," she says. "It's my understanding that there's no statute of limitations on that."

Kritzer finds the whole affair disheartening. "It's very scary that, thirteen years after an alleged incident that never even happened, José is put in a position where his job, his reputation, and, indeed, his freedom, are in danger."