At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, a woman named Madeline Davis called for something new: The party, she said, should include gay rights in its platform. Davis, the first out lesbian delegate at a major party convention, declared that gay people were "here to put an end to our fears."

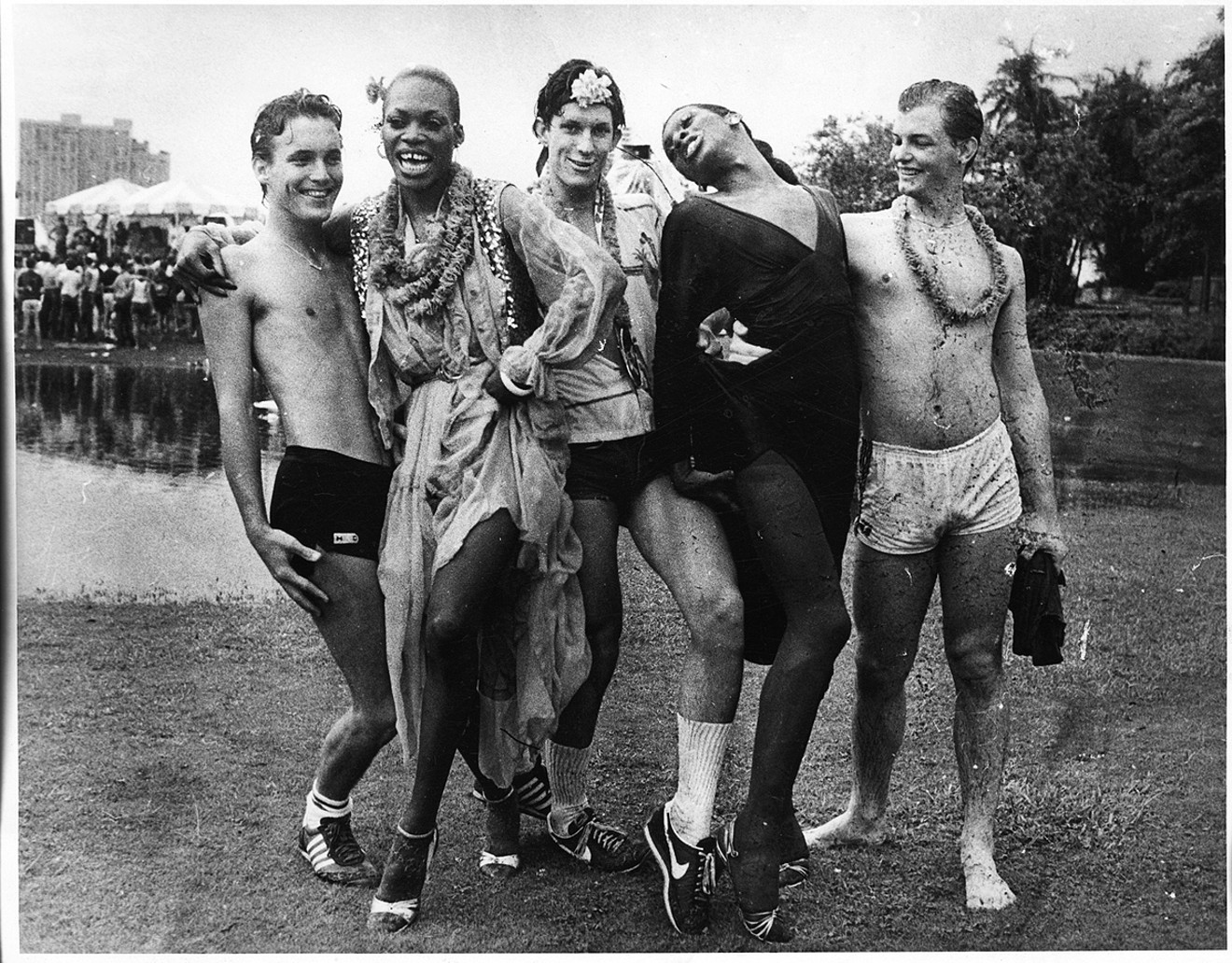

It happened here, in Miami Beach. And it was just one of the watershed moments the Miami area saw in a 12-month period. A few months before Davis' speech, the city played host to what some believe to be the first organized gay pride week, which began as a protest against the city's anti-cross-dressing law. Weeks later, a federal judge struck down that measure.

The DNC was held in July, followed a month later by the Republican National Convention, which was also hosted by Miami Beach. Once again, gay rights activists were a major presence, holding protests outside.

Miami's place in LGBTQ history is often overlooked. But from its earliest days as an untamed, fantastical playground for the rich to its emergence as an ever-changing global mecca, the city has been the setting for moments of both triumph and defeat in the slow march toward gay equality — moments that had profound implications beyond the city's borders.

These moments form the backbone of an exhibit opening Saturday, March 16, at HistoryMiami. Curated by Julio Capó Jr., a Miami native and associate professor of history at

"Miami has never, I think, been taken seriously as a city worthy of enough attention and worthy of serious scholarly study," says Capó, author of the book Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami Before 1940. "And it is such an important space that really helped shape not just its local politics, but certainly national and even international conversations."

From the city's earliest days, long before the beginning of the gay liberation movement, queer people had carved out places for themselves in Miami — much to the chagrin of the conservative ruling class. In later years, the passage of

Here are five moments Capó says best represent Miami's rich LGBTQ history, from past to present and well known to mostly forgotten.

Ku Klux Klan Raid on La Paloma Gay Bar, 1937

The night of November 15, 1937, nearly 200 men and women in white hooded robes stormed into the Miami-area nightclub

For some time before the raid, residents had been complaining about the "immorality" of the club on NW 79th Street. Located in an unincorporated part of the county, La Paloma billed itself as a Miami hot spot, boasting in Miami Herald ads: "Never a dull moment." Its stage featured women performing stripteases, as well as performers

Even amid constant protests from locals, and despite Sheriff David C. Coleman declaring the club a "menace" to the city, its doors remained open. While some residents wanted Miami to be a good, clean city of the new South, places like La Paloma were central to its reputation as a wide-open fantasyland, Capó says. Believing the city's morality was at stake, the Ku Klux Klan took matters into its own hands.

"They thought they were doing the work in the absence of police enforcement," Capó says. "If they couldn't do it in an official capacity, these terrorist groups found ways of doing what they thought was moral cleanup."

In the aftermath of the raid, the sheriff pledged to keep La Paloma closed. But owner Al Youst insisted the closure would be only temporary and only for repairs. The Herald quoted him as promising the club would reopen with "spicier entertainment than ever." Sure enough, La Paloma was back in business within weeks. A new show debuted, this one with performers dancing cheekily in white hoods.

"To me, it's subversive," Capó says. "You think you're going to strike fear in us? We're going to remove that fear, take away the power of it in ways that I find so powerful in terms of both resistance and resilience."

Marriage of Charlotte McLeod, 1959

When Charlotte McLeod donned a white satin dress and exchanged vows with Ralph Heidal during a wedding ceremony at a Miami Baptist church in October 1959, few knew she'd been assigned male at birth. It was the Herald, in a front-page story headlined "Ex-GI Changes Sex — She's Now a Miami Bride," that broke the news a month later.

"I'm going to call myself a doctor and get some tranquilizers," the Rev. Dr. A.H. Stainback, who officiated the marriage, told the newspaper. "I wonder what the deacons will say."

Born in 1925, McLeod spent the first 28 years of her life struggling to fit in as male. She would later tell reporters she had always felt and thought like a woman. After the highly publicized case of Christine Jorgensen, who in 1951 underwent gender reassignment surgery in Denmark, McLeod sought to do the same.

But when she arrived in Denmark, she learned that hype over the Jorgensen story had prompted a law limiting the procedure to Scandinavians. Desperate to correct what she considered nature's mistake, McLeod turned to an underground Danish doctor who nearly killed her while performing the procedure on his kitchen table.

"I risked all on the dangerous gamble of surgery," McLeod wrote in a tell-all for Mr. magazine. "I did so because I found life so unbearable that I

Emergency surgery corrected the botched operation, and in 1954, she returned to the States as Charlotte. She arrived

Many years before Caitlyn Jenner, marriage equality, or even the coining of the term "transgender," McLeod's marriage to Heidal sparked conversations about the meaning of gender, as well as who should be allowed to marry, Capó says.

"There is this moment where they say, 'Well, there's nothing in our laws that

Nevertheless, he says, McLeod was "so important in challenging a lot of the preconceptions about gender and about sex."

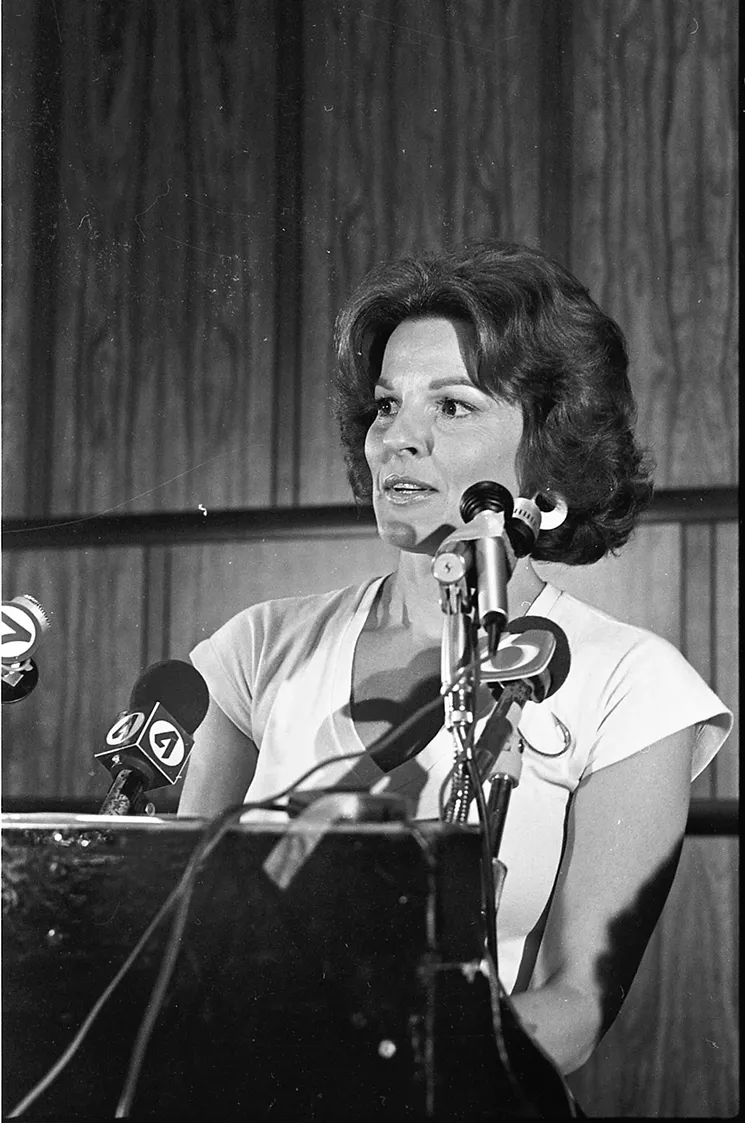

Anita Bryant's "Save Our Children" Campaign, 1977

As a newly elected Metro-Dade commissioner in 1976, Ruth Shack thought adding "affectional or sexual preference" to the county's existing

"I mean, any Catholic, any Jew, any Irish person — any of these people who had felt discrimination in their past would certainly understand what it was like to be discriminated against because of who you were and how you were born," says Shack, a veteran of the civil rights and women's liberation movements.

She couldn't have anticipated that an Oklahoma-born, Miami-based celebrity named Anita Bryant would come out in fierce objection to the amendment — or that her involvement would turn the local ordinance into a national political cause.

Bryant — a 36-year-old former Miss America

It was one of the first major campaigns against the gay rights movement sparked by Manhattan's Stonewall Riots, which followed a police raid of a club that welcomed gays in 1969. At the same time, Bryant's crusade — which branded gay people as perverts and linked homosexuality to pedophilia — united and activated the gay community in a way that had never been seen before.

"The Anita Bryant campaign, to me, is one of the most, if not the most, pivotal or seminal moments in politicizing gay people in the United States," Capó says.

When Save Our Children collected enough signatures to place the ordinance on the ballot, it drew a record number of voters and was defeated by a wide margin. "I was heartbroken," Shack says today. "I think that's the only word I can use." Bryant's group, meanwhile, was invigorated by its victory and set about defeating similar laws in cities across the nation. Out of that movement came the Moral Majority, the religious right, and the culture wars that would shape America for decades to come.

But so, too, came the gay community's galvanizing to fight back.

"There are enormous ramifications that start here," Capó says.

The Mariel Boatlift, 1980

Manuel Rodriguez and Casimiro Gonzalez met around noon at a Havana movie theater in 1967. They didn't stop talking until 11 p.m., and soon enough, the two young men became inseparable. But in Cuba, they ran the risk of being thrown into a forced labor camp if their relationship was discovered by the dictatorship, which considered homosexuality to be antirevolutionary.

"Everything was in secret," Rodriguez says in Spanish.

When Fidel Castro opened the port of Mariel, Gonzalez was quick to leave the communist regime. "I couldn't keep living that way," he says. Rodriguez arrived in the United States soon after, and the two Marielitos settled into life in America.

The impact of the Mariel Boatlift on Miami is well documented. But perhaps less understood is its influence on LGBTQ politics. Beyond swelling the city's gay population with queer exiles such as Rodriguez and Gonzalez, who were eager to escape oppression in Cuba, the mass emigration forced a kind of reckoning over

At the time of Cuban refugees' arrival on U.S. shores, Capó says, the country barred homosexual foreigners from entry. That law was passed in 1952 and would remain until 1990. But the Mariel Boatlift put the States in a difficult position as it welcomed anticommunist exiles amid Cold War tensions. Among the nearly 125,000 people fleeing Cuba were thousands of self-identified homosexuals the Castro regime had deemed undesirable.

"What is the United States going to do, send them back and say Castro is right? It would be way more embarrassing," Capó says. "In this way, the United States' long-standing anticommunist rhetoric trumped its long-standing anti-gay immigration policy."

So the U.S. accepted the Marielitos, with the Justice Department instituting what Capó calls a "proto 'don't ask, don't tell' policy." Rather than screening for homosexuality, immigration workers would deny gay people only if they disclosed their sexual orientation unsolicited — a policy change that ultimately would lead to immigrants being granted asylum on the basis of their sexuality.

Meanwhile, America became a permanent home to somewhere around a thousand gay Marielitos, including Rodriguez and Gonzalez, who, after more than 50 years together, are married and living in Miami.

"As soon as I planted my feet in this country, I was sure of what I was doing," Gonzalez says. "I said, 'This is going to be our country.'"

First Legal Same-Sex Marriage in Florida, 2015

The morning of January 5, 2015, Catherina Pareto and Karla Arguello could barely eat breakfast. The longtime couple was anxious to find out whether Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Sarah Zabel would lift a stay on her ruling that the state's gay marriage ban was unconstitutional. Doing so would pave the way for them to marry 15 years after they began wearing wedding rings.

Hours later, the two stood in white dresses in Zabel's courtroom and became the first same-sex couple to be wed legally in Florida. As cameras flashed, the judge told the two that their vows were "public confirmation of [their] trust and love for each other." Reporters packed the courtroom for the historic moment.

"It has been a very emotional day," Pareto told New Times after the ceremony. "Karla and I are beyond ecstatic that we are the first."

Over the next week, gay couples said "I do" across the Sunshine State, the 36th to legalize same-sex marriage before it became the law of the land later that year. With marriage equality came legal and medical benefits previously available only to heterosexual couples. But beyond those rights was the symbolic significance, Capó says: "What it means for people's children, their families, to say, 'We are on equal footing in the eyes of the law,' is massive."

That the first same-sex marriage took place in Miami-Dade County — where Anita Bryant began her national crusade against gay rights and where so many other pivotal moments played out — was fitting.

"To see it happen here first," Capó says, "is meaningful and powerful."

"Queer Miami: A History of LGBTQ Communities." March 16 through September 1 at HistoryMiami Museum, 101 W. Flagler St., Miami; 305-375-1492; historymiami.org. Tickets cost $10 at the door.

Assistant culture editor Celia Almeida contributed to this piece.