They took in their new surroundings at the Homestead Temporary Shelter for Unaccompanied Children — the tall chain-link fences, the massive white tents, the rows of bunk beds — without knowing exactly where they were or how long they'd be there. Weeks or months later, they'd settled into a routine of classes, counselor-accompanied bathroom breaks, and recreational time in the fenced fields outside the facility. They strove to follow rigid rules that limited phone calls to two a week and banned physical contact of any kind — even hugs and handshakes — fearful that breaking them might mean having to stay longer or even being deported to countries they’d fled because of murderous gangs or stifling poverty. Some had heard the American government might decide they were a "bad person."

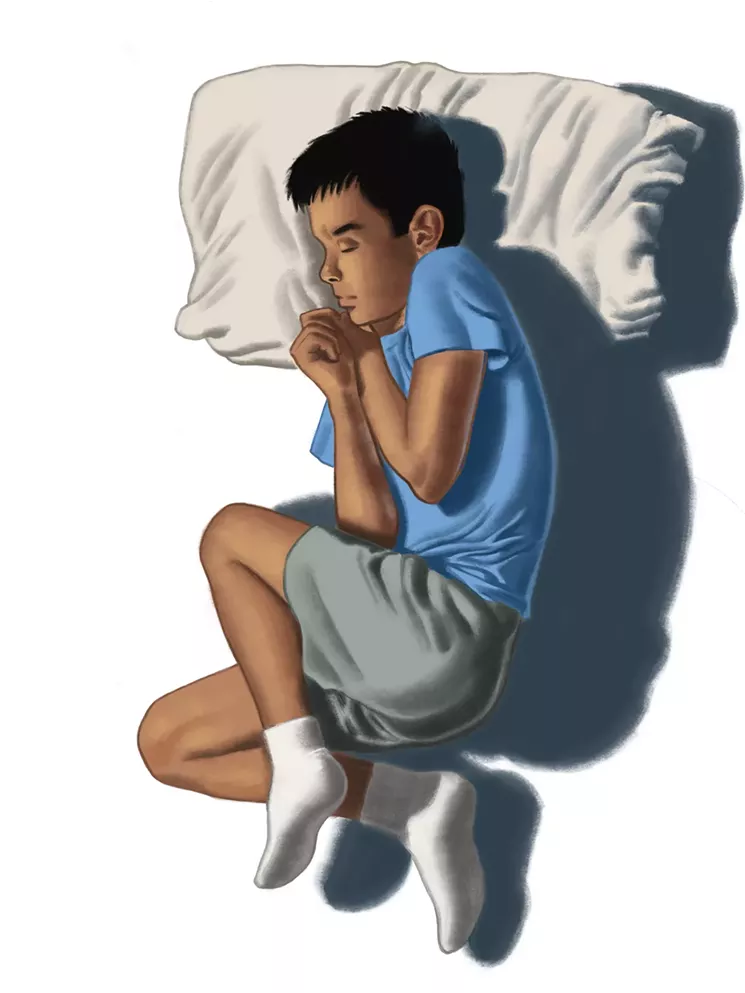

The children didn't know when they might be released even though many had family members in the United States who wanted to take them. They heard rumors of kids who tried to escape and were shipped off to worse places. They felt dismayed when guards took away the friendship bracelets they'd made to pass the time, or the snacks they'd stowed amid their belongings. They cried themselves to sleep, marked birthdays that passed without anyone singing to them, and tried to follow the advice their parents shared over the phone: Be patient and don't cause trouble.

Some feared they might never leave the facility, which one child described as "almost like being in a prison" where "all that’s missing are the cells." Another saw a boy try to run away and understood the impulse: "We’ve been held here for so long it feels like we are prisoners."

Since the Trump administration quietly reopened the Miami-area shelter almost a year and a half ago, the thousands of kids inside have been seen only in the shadows. Driven behind the gates in buses, they've disappeared into the tents and trailers that make up the facility, which is run by a private company, out of view of Florida child-welfare officials. They've only been seen running around the fields outside, their heads covered by orange caps. Why they came to the United States, what they've experienced in Homestead, and how they feel about it remained unknown — until just recently.

Hundreds of pages of documents filed in a California federal court May 31 bring the children and their stories into sharper focus. Included in a motion seeking to force the government to follow the Flores settlement — a Supreme Court agreement regulating the treatment of detained migrant children — the records offer what is so far the clearest window into life as a child held at the Homestead shelter. In written declarations, 75 kids identified only by their initials detailed their journeys to the United States, their motivations for coming, and the emotions they felt while detained.

Already some of the circumstances they described have changed. Attorneys and social workers took many of the statements last summer and fall, when the facility still held children taken from their parents under the Trump administration’s "zero-tolerance" policy. (The federal government says it stopped splitting families last summer; authorities say the kids currently detained in Homestead arrived in the States alone.) And just this month, the administration stripped away the recess time and educational services many of the interviewed children described fondly.

Still, the statements represent the first chance the public has had to hear from the children themselves. These are their stories.

"I cried every day because I didn’t want to be there."

Alone in a room filled with bunk beds, M.G. could only wonder what he'd done. The youth counselors who stood watch outside his door wouldn't say. They simply stared as he ate his meals in silence. Occasionally, one of them would talk to him. Otherwise, the Mexican teenager sat in total isolation, barred from going to school or recreational activities with the other kids."I cried every day because I didn’t want to be there," he said. "I felt so alone that I was even losing my appetite. I didn't leave the bed. I didn’t have anything to do. At one point, they brought me Monopoly, but I couldn’t play alone."

Eight days passed. Finally, a woman told M.G. he could come out if he behaved. But he didn’t know what he’d done wrong. He’d never been reported for misbehavior at the Homestead shelter.

It had been weeks since he arrived, shipped to South Florida after being caught by immigration officials when he crossed into the United States and fell to the ground. A Border Patrol agent had put his foot on M.G. and asked, "Do you want to run?"

He thought being at the Homestead shelter was almost like being in prison. Guards searched the dorm rooms while the kids were gone and took the cookies M.G. had saved from lunch. He spent his 16th birthday crying. Early last July, he asked to go home. That was when he was sent to the roomful of bunks and left there by himself for more than a week. He never found out why — not even when his mom called the detention center to ask.

"I was never told why I was put in there," he said. "When I got out and first felt the sun, it felt amazing."

"They would yell at me telling me to remain quiet."

For two long days, N.J. waited to see her father. She had been flown from the Homestead shelter to Texas July 25 and told that her family was being reunited on the government's orders. Hours passed, and N.J. was taken somewhere to sleep. The next day, she waited until falling asleep again. At 3 in the morning, immigration officials woke her and told her to gather her things. She was going back to Homestead."I asked what had happened to my father, and they told me they could not reunite us yet because there had been some complications with my father's flight," she said. "To this day, I still haven’t spoken to anyone to find out what is going to happen to me and when I will be reunited with my father."

The two had come to the States together, accompanied by N.J.’s stepmother and 3-month-old sister. They left Guatemala because they were being extorted by gang members with no recourse: Local police did nothing when her father was stabbed and her family was threatened with kidnapping.

They crossed the border in Texas and asked for asylum. Immigration officials took them to a facility where they were separated. Again and again, N.J. asked the guards where her father was and if the two could be together.

"But they would yell at me telling me to remain quiet and saying that I didn’t belong because the United States government didn’t want Guatemalans, Hondurans, or Salvadorans in the United States," she said.

Eventually, she wound up in Homestead, where she learned her father was in a detention center in Texas. Over the phone, he told her he was seeking asylum for the whole family. After the failed reunion in Texas, though, N.J. wasn't sure what had happened to him. No one seemed to know. She worried his life would be at stake if he was forced to return to Guatemala.

"I hope I can remain in the United States," she said, "and start a new life with my family."

"I did not know when it was day or night."

A devout Christian, D.J. wouldn’t repeat the insults and obscenities the guards spewed at him and the other children at la perrera. He was hungry and cold at the Texas detention facility, where migrants slept on the floor and used flimsy foil blankets for warmth. The lights were on at all hours, and D.J. "did not know when it was day or night." He felt terrible, but if he and the other children tried to talk to one another, the guards became incensed."The guards insulted us using the worst and ugliest words imaginable," he said. "They insulted our mothers too."

The 16-year-old had left Honduras and traveled alone to the United States, reaching Texas this past March. Border agents stopped him after he crossed a river. After four days inside la perrera, D.J. landed at the Homestead shelter. A few weeks into his stay, he was finding it difficult to adjust. Back home, he was used to being hugged and told good night by his family.

"I don’t have anyone to do that for me here," he said. "I cry in my room some nights. I try to distract myself by reading the Bible, listening to music, or talking with other kids. But it is most hard and sad to think about my family because I miss them a lot."

He knew that other kids — the ones who had no one in the United States to take them in — had it worse. D.J. had an aunt in Maryland who was trying to set up a fingerprinting appointment so the government could verify the two were related and he could be released to her. Some of the other children weren’t so lucky. They didn’t know whether they’d ever be allowed to leave.

"These children are suffering the most," D.J. said. "They do not have energy, they do not have hope, they do not want to talk with anyone, and they are not motivated to play. One of my friends has no one to receive him in the United States. When he is in his room, he just cries and cries."

"I felt alone in a place with strangers."

There was no milk, so M.R. gave the babies juice. Newly torn from her father, she found herself caring for a 1-year-old and a 2-year-old at a facility somewhere near the southern border. The guards were mean and the shelter was freezing cold, but M.R. was there to change and feed the babies when they woke up screaming."It was really bad because the babies would cry at night missing their parents," she said.

At home in Honduras, M.R. was one of 12 siblings. There wasn’t enough food or clothing for everyone. She and her father had hoped the United States would offer the family a better future. They came here together in May of last year and presented themselves to Border Protection officers, who soon separated them. They weren't allowed to say goodbye.

M.R. spent two days in the shelter with the babies before immigration officials told her she was going to "a better place." They put her on a bus and drove her to the airport. They didn’t say where the plane was going.

"I was afraid and sad and crying because I did not know where my dad was," she said. "I felt alone in a place with strangers."

After arriving in Homestead, M.R. still felt overwhelmed by sadness even though she liked her teacher and didn’t feel mistreated. She talked to her mom twice a week but wanted to talk to her dad too. A whole month passed before she found out he’d been deported.

"I would like to talk to my mom in Honduras more often," she said. "I tell her how I am doing here. She gives me advice to be good and do not get in trouble. I think I need more time to talk to her. I do not talk to my father often because now that he is deported to Honduras, he is always working."

"I have been here so long."

He didn’t want his mother to worry, so A.A. never told her about his nose. A boy in his classroom, Bravo 11, had punched him without provocation, making blood gush from his nose. The youth counselors didn’t notice. A.A. asked to go to the medical unit, but no one took him. In his twice-weekly phone calls with his mom, he never mentioned any of it."Already it is very hard," the 14-year-old said. "We both cry on the phone."

A.A. had left Honduras with his maternal aunt in late 2018. Border agents separated them, and he spent a day and a half at la hielera before being taken to Homestead December 3. There, he took classes with about 35 other boys, although it was difficult to learn because the lessons started over every time new kids arrived. They studied every day — weekends were supposed to be for movies, religion, and rest, until the director decided it was "better for us to study English."

The rules were strict at Homestead, and A.A. knew it was important to follow them. His social worker had told him that each report of bad behavior would delay his release by 15 days. He'd also heard that a judge would see any reports in his file and hold it against him when making decisions about his case. But it didn’t seem to go that way with the boy who had punched him.

"The one who broke my nose was released after three weeks, while I am still here," A.A. said. "It is not fair, but the social worker tells me every case is different."

By the end of March, he had been at the shelter almost four months. He talked to his social worker on the computer once a week for updates about his case, and he felt frustrated when internet problems cut their conversations short. He was eager to leave Homestead and live with his paternal aunt in Virginia.

"I have not seen my mom or any family for so long," he said. "I have been here so long."

"The first time I talked to my mom, I cried so much."

When a gangbanger began lurking outside her high school each day to tell her he wanted to be her boyfriend, Z.P. knew she had to leave El Salvador. She used to know a girl who dated a boy in a gang. Gang members killed her, cut off her arms and legs, and used her WhatsApp account to send her mother a photo."My cousin, who is a gang member and knows the guy who was bothering me, came to warn me," Z.P. said. "He told me he heard them talking about doing terrible things to me and that if I could flee, I should."

She began the trek to the United States in March. On the way up through Mexico, an armed man attacked the car she was riding in. Some of the migrants inside were hurt. Terrified, Z.P. sprinted from the car and into the woods to hide.

"My legs were shaking so hard I could barely run," she said. "I was so scared. In that moment, I regretted trying to flee because I didn’t want to die on the trip. I wanted to stay with my mom, but I also could never make my mom go through me being killed in El Salvador by the gangs, so I had to leave."

She entered the States near McAllen, Texas. Border patrol officers took her to la perrera. There, the bathrooms were so dirty that Z.P. tried not to drink any water. Her head ached, but she didn’t say anything, believing no one would care. The crinkling of the foil blankets put her on edge and added to her unease. "I never want to see aluminum again after using those blankets," she said.

After four days in that "awful" place, Z.P. was send to the Homestead shelter. Even after just a week there, she longed to be released to her grandpa, a legal resident who lives in Maryland. No one was hurting her at Homestead, she said, but it wasn't like being with family.

"The first time I talked to my mom, I cried so much that I think I worried her," she said. "So I tried not to cry after that."

Asked about the experiences detailed in the children's declarations, a spokesperson with the Department of Health and Human Services responded with the following statement:

As a matter of policy, HHS does not comment on matters related to pending or ongoing litigation.U.S. Customs and Border Protection did not respond to a request for comment. New Times also contacted Caliburn International, the for-profit company that operates the Homestead shelter. In February 2018, the firm's subsidiary Comprehensive Health Services Inc. was awarded a $31 million contract to oversee the shelter. In April 2019, Caliburn won a $341 million, no-bid contract to expand the facility. A company spokesperson did not respond to New Times’ request for comment.

The safety and care of unaccompanied alien children (UAC) is our top priority.

HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) has worked aggressively to meet its responsibility, by law, to provide shelter for unaccompanied children referred to its care by the Department of Homeland Security while we work to find a suitable sponsor in the U.S. Since opening in March 2018, over 13,053 UAC have been placed at the site and more than 10,668 have been discharged to a suitable sponsor (usually a parent or close family relative).

By activating temporary shelters — and having potential shelters on reserve status — ORR has the capacity to respond to ever-changing levels of referrals and in this case an emergency situation at the border.