On June 13, Chicago's Chance the Rapper will arrive at the American Airlines Arena on a wave of celebration and commercial success. Last year, his mixtape Coloring Book became the first streaming-only release to make the Billboard 200. The tape was also a critical smash, with its intense, bright fusion of gospel and rap earning it a 9.1 from Pitchfork. He's a commercial behemoth, appearing in endorsements for big brands such as Nike and Kit Kat. All the while, he is proudly independent and unsigned to any record label. He even donates to charitable causes such as Chicago's public schools. People have asked him to run for mayor — for president, even.

All in all, Chance has a sterling reputation built on a message of faith and sincerity, as well as a squeaky-clean image emphasizing his self-made, entrepreneurial approach to music. But beneath the surface, a different picture emerges, one of an artist more well-connected and ambitious than he cares to admit.

Chance is part of a rising wave of “positive” rappers, whose music is fun, nostalgic, and thematically unchallenging. They use cartoonish embellishments, such as the bright, simple piano chords in D.R.A.M.’s hit “Broccoli” and Kyle’s “iSpy” — not to mention the entire oeuvre of Atlanta’s Lil Yachty — over party-ready trap beats in their production. And they match raps about sex (rarely drugs) with lines about how much they love their mothers. Their songs are adult yet childlike, like using finger paint to cover the naughty bits of a Playboy. On Chance’s record Coloring Book, for instance, the major themes are God, family, success, and the uniqueness of every individual. Chance calls himself the “blueprint for a real man” who will “get my word from the sermon” and pass it on to his daughter.

While the artists who play this music possess a seemingly inexhaustible well of happiness and satisfaction, they also largely disregard the struggles of poverty and violence that defined earlier eras of hip-hop, mostly because they haven't lived them. The 19-year-old Yachty, who is the chief scapegoat for his generation, was raised middle class and networked his way into a Kanye West fashion show before even dropping a tape. He frequently sees his authenticity called into question for refusing to have an opinion on the Notorious B.I.G and other '90s rap icons.

Video reviewer Anthony Fantano has called Chance an instigator of rap’s “punk” phase and cited his rejection of cultural tradition and protocols as evidence. And Vince Staples, who raps about poverty and violence, has argued that party music is no less genuine than music from the streets. “Someone saying they wanna go to a party is real,” he told Time in 2015.

Chance is somewhere in between when it comes to this perception of "realness." He doesn't make straight party music, and he's not an intellectual. He grew up well-to-do on the South Side of Chicago with a father who works in the mayor's office. (He's also seen his share of violence.) His music has certainly proceeded in one direction since his breakout tape, Acid Rap, was released in 2013. On that record, he approaches the drug use and gun violence that plagues the South Side of Chicago with honesty and apprehension. On the melancholy "Paranoia," he rides through the city "with my blunt on my lips / With the sun in my eyes and my gun on my hip." In other words, a blunt dulls the pain, while a gun gives protection. Sounds pretty classically hip-hop.

This morally complex version of Chance has been scrubbed away on recent records. The playground sweetness of “Sunday Candy” on Surf gave way to last year’s gospel explorations on Coloring Book, one of the sunniest, most pointlessly celebratory, poorly mixed albums in memory. It practically screams at the listener on songs like “Angels,” with its fast-motion footwork beats and shrieking choir. It’s as if Chance decided catching flies with honey wasn’t enough and dumped a pound of sugar on a plate of Communion wafers instead. Bursting with joy, it tries to be both a preaching record and a party record, and fails at both. Chance heaps adoration upon the Lord on “How Great” just a few tracks after feeling up some girls with Justin Bieber in “Juke Jam."

And though critics have praised his "independent" approach, Chance clearly has lofty commercial aspirations. Besides appearing in shoe and candy ads, he’s also modeled for an H&M collaborative collection with Kenzo and signed a deal with Apple Music for exclusive streaming rights on Coloring Book in its initial period of release. Apple and H&M, meanwhile, have been criticized for abusive labor practices. Surprisingly, most of the criticism he received regarding the Apple deal surrounded his integrity as an unsigned artist. "@apple gave me half a mil and a commercial to post Coloring Book exclusively on applemusic for 2 weeks," he wrote on Twitter, calling them "good people" and remaining adamant about his independent status. (He was more concerned about ensuring his record was eligible for Grammy nominations.) This type of response is common among artists of his generation, who display an ambivalence toward the ethics of working with major corporations. To someone like Lil Yachty, taking deals from Sprite, Nautica, and Target isn't "selling out"; it's the object of the game.

Chance wants to present as a religious family man making a jubilant work of heavenly devotion but simultaneously be a sex symbol and the life of the party. He wants to be the cool youth minister but instead comes off as the overly friendly guy who slyly tries to slip Jesus into every conversation. And he wants to take corporate money while absolving himself of what he represents by doing so. Does his gospel have its limits?

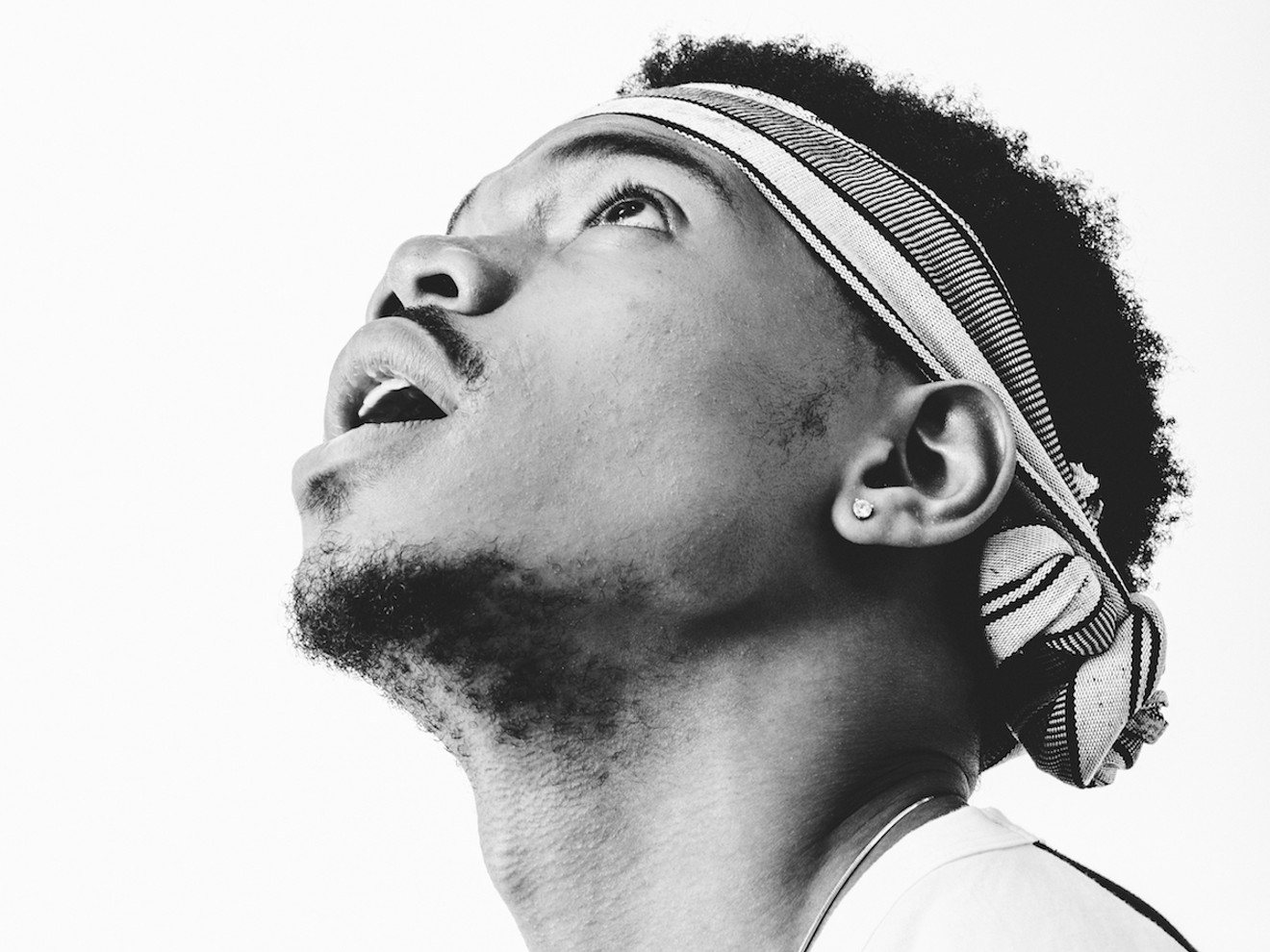

Chance the Rapper

8 p.m. Tuesday, June 13, at American Airlines Arena, 601 Biscayne Blvd., Miami; aaarena.com; 786-777-1000. Tickets cost $45.50 via Ticketmaster.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]