1. Amertec Building, 1967-2017

This quasi-freeform building, an anomaly of architecture in hodgepodge Hialeah, was the brainchild of Chayo Frank, who designed the office building for his father’s woodworking and store-fixture-manufacturing business. Inspired by his “love of the exotic beauty of tropical nature,” he used sprayed concrete and curved rebars to create a bizarrely unconventional structure in "La Ciudad Que Progresa." Progress didn’t keep up with the sculptural design of the building the architect describes as an “organic entity,” which it certainly resembled until it was demolished earlier this year. It had been surrounded by drab, industrial warehouse-style businesses on a busy street without a single tree. Learn more about the architect at chayofrank.com.

2. Tobacco Road, 1912-2014

Perhaps Miami’s most famous modern demolition, recent and boozy enough for millennials and baby boomers alike to regret, is Tobacco Road, proud holder of the city’s first issued liquor license. The structure, originally a modest-looking bakery before it became a watering hole, never really changed. The dark two-story dive just south of the Miami River, however, wasn’t so humble in reputation. Over the years, the Road welcomed famous folks and blues musicians, as well as thousands of patrons looking to quench their thirst. Even though it survived the great wars of the 20th Century and Prohibition, it couldn’t compete with corporate giants that bought out Brickell for megadevelopments. Miami’s beloved joint was demolished October 26, 2014, just days after its 102nd anniversary, a date that could go down as the city’s own “the day the music died.”

Courtesy of Alex Feldstein

Anyone old enough to have watched Miami Vice when it first aired in the mid-1980s will certainly remember Coconut Grove’s landmark Grand Bay Hotel, a bastion of '80s glamour. The Mobil five-star-rated hotel was developed by the late Sherwood “Woody” Weiser, one of the city’s leading philanthropists. With its pyramid design and large red sculpture (Windward, by Alexander Liberman), the hotel was a visual knockout in the '80s. It hosted a who’s who of celebrities, including Michael Jackson during his Orange Bowl concert. The Grand Bay, which housed then “it” nightclub Regine’s, gradually lost its luxury ranking to South Beach properties and was razed to make way for BIG, the Bjarke Ingels “twisting towers” development. The sculpture remains as a reminder of the hotel’s former glory.

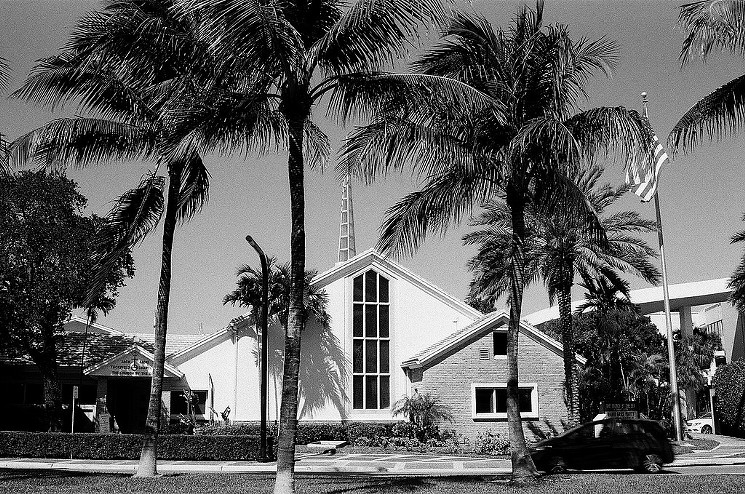

4. Church by the Sea, 1947-2011

Church by the Sea’s humble beginnings go back to post-World War II, when Army families gathered informally for worship in the neighborhoods just north of Miami Beach. Over time, the structure that housed the congregational church would reflec the design work of illustrious Miami architects Russell Pancoast and Alfred Browning Parker. When Bal Harbour Shops offered to buy the property to expand its retail enterprise, faithful members protested, but the church never made the cut with the Miami-Dade Historic Preservation Board. In a not-so-grand stroke of irony, the demolition team showed up just days before Christmas. The church persevered in true Christian form (and with a good hand in business smarts) by collaborating with stakeholders in the area, including Bal Harbour’s Whitman Family Development. The St. Regis resort currently hosts worship on Sundays, and the church will eventually move to a site it recently purchased in adjacent Bay Harbor. Visit churchbythesea.org.

5. Fontainebleau Hotel Mural, 1985-2002

In 1985, Stephen Muss, owner of the Fontainebleau (then a Hilton resort) in Miami Beach, chose famous muralist Richard Haas to give the property’s Sorrento building a face-lift with a grand visual statement. A six-story trompe l'oeil on Collins Avenue tricked viewers into thinking they could see the property’s iconic Château building through an enormous arch in a wall flanked by columns. By 2002, more modern tastes prevailed: a direct view to the crescent-shaped building that Morris Lapidus designed in the 1950s. The Sorrento went down with the mural and made room for the Fontainebleau II condo/hotel project.

Courtesy of HistoryMiami

Back in the day when an afternoon at the ballgame cost less than bottled water at today’s Marlins Park, Miami’s baseball fans enjoyed their favorite sport at the stadium located in Allapattah. Built in 1949 for spring training, the park held 13,500 people and hosted the Brooklyn Dodgers, Los Angeles Dodgers, and Baltimore Orioles. The Miami Marlins' minor-league team also played there in the late '50s. In 1987, the stadium's name was changed to Bobby Maduro, after a Cuban baseball entrepreneur, but the sport would soon become a thing of the past at the venue. When the Florida Marlins first stepped up to the plate in 1993, the team chose Joe Robbie Stadium as its first home. Bobby Maduro Stadium succumbed to neglect and was razed to make room for an affordable-housing project in the early 2000s.

Courtesy of HistoryMiami

Miami has seen its share of failed malls, and South Miami’s mammoth Bakery Center is one of them. Developer Martin Margulies (also a major Miami philanthropist and art collector) had big dreams for the property built on the corner of high-profile South Dixie Highway and Red Road, where a Holsum bakery once stood. The enclosed mall, nicknamed “the pink elephant,” marred the cityscape and never attracted major merchants like its counterpart Dadeland just down the road, but it survived for a few years thanks to the AMC multiplex that's still there. Today the land is home to the open-air Shops at Sunset Place and is surrounded by small retail shops.

State Archives of Florida/Johnson

Long before Miamians saw invasive species of pythons in their backyards, scientist Bill Haast was handling the slithering reptiles at Miami Serpentarium on South Dixie Highway at SW 128th Street in what is now the Village of Pinecrest. Haast was a showman who grabbed snakes barehanded, and although a little worse for wear from bites, he became a leader in venom and antivenom research. The concrete-and-stucco cobra statue stood 35 feet high and was donated to South Miami Senior High (home of the Cobras) in 1984 when Haast closed shop. The statue suffered damage during the move but was repaired and displayed atop the school’s building until Hurricane Andrew took it down in 1992.

State Archives of Florida/Willard

A giant capital letter "D" atop a concrete tower still soars over this 1960s mall built when Kendall was truly the boondocks, inching out to the west past a new Palmetto Expressway and a two-lane Kendall Drive. But that beacon for shoppers at the mall then nicknamed “Deadland” hardly overshadowed a fountain statue of a seahorse at the center of the mall that was moved outdoors sometime after a renovation in the '80s. The seahorse wasn’t the only statue: A frog, turtle, and llama completed the menagerie. The seahorse’s whereabouts today remain a mystery. One rumor places it (or pieces of it) at the bottom of Snapper Creek Canal.

10. Prins Valdemar, 1892-1952

Built in 1892, the 241-foot, four-masted Danish barkentine Prins Valdemar sailed the seas in various roles. During World War I, the ship was a gunrunner for the Germans. It later transported lumber, which is what brought the ship to Miami during the 1920s building boom. In 1926, Prins Valdemar capsized in Miami Harbor’s turning basin, and by 1928, a salvaged version of the ship became a floating aquarium docked at Bayfront Park. The massive vessel transformed into a landlocked attraction in 1937 and then serves as a clubhouse for officers during World War II, an aquarium once more, and a civic center until it became an unsafe, dated eyesore by the early 1950s. Not all of ship became scrap metal: Its wheel is on display at HistoryMiami, and its anchor decorates the entrance to the Miami Yacht Club.