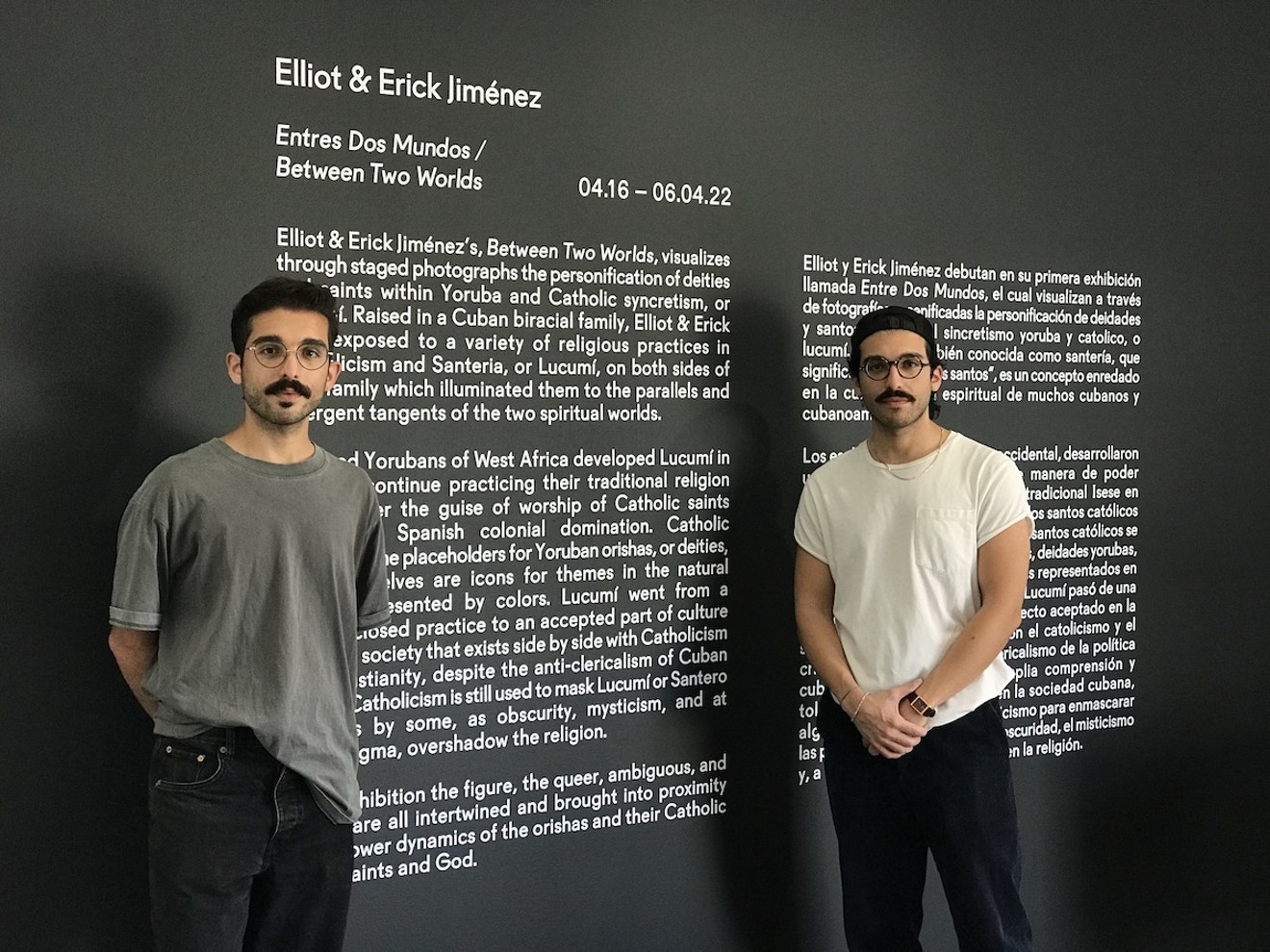

"Entre Dos Mundos" — which opened April 16 and runs through June 30 — walks you through the twin brothers' take on the religion’s mix of Roman Catholicism and the culture of the Yoruba, one of the largest Nigerian ethnic groups in West Africa.

“When the Spanish colonized Cuba, they enslaved Yoruban people and forced them to convert from their original faith of Isese to Catholicism,” Erick explains to New Times. “In order for them to continue their practice, they concealed their gods, the deities based on Catholic saints with similar ideals, which is sort of what the show visualizes.”

The series ventures outside of the twins’ 14-year career in fashion photography. (They've worked for Vogue, Allure, Hermés, and Highsnobiety, to name a few.) Though their career took off in New York City, the Miami natives brought "Entre Dos Mundos" home.

Each editorial-style photograph honors Lucumí saints through elegant, grandiose garments worn by ambiguous generations of Caribbean, Latin American, and African models, including one person with a surprisingly close tie to Yoruba.

“It was really interesting to work with one of these guys because essentially he’s from Nigeria, where the Yoruban people came from, but he had no idea or understanding of their religion,” Elliot explains. “Of course, you think about the whole image, but especially the people who we’re photographing, for spiritual reasons.”

However, this knowledge gap between Yoruba natives and Lucumí beliefs is not uncommon. Elliot emphasizes the impact colonization had on those now living in America.

“Here in Miami, there’s such a dense population of Cubans, so most people have some idea of this religion, even if they’re not directly connected to it,” Elliot says. “I know people come in with so many assumptions or ideas of the religion already.”

The figure wears a chained head garb as armor to personify Saint Barbara, the goddess of war.

Photo courtesy of Spinello Projects

“Every saint is connected to a color. Like mine is Oshun, who is represented by yellow, so you could give them offerings like yellow flowers,” Elliot says. “It’s believed that each orisha chooses someone when you’re born to become sort of your guardian throughout life.”

But as you enter each room, you’ll notice dark, eerie tones within the photographs, which personify the mystery behind Lucumí.

“They have temperaments, personalities, flaws,” says Erick. “If you know the orisha, and you understand who they were when they were human, they have certain traits representative of who you are.”

Erick drew inspiration from his own orisha, which is often represented by abundance and water — both flowing and constant.

“For my orisha, Yemaya, you can go to the ocean to pray or embrace her,” Erick explains. “Some others are connected to palm trees so you could meditate under the trees.”"People come in with so many assumptions or ideas of the religion already.”

tweet this

These rituals of meditation and prayer are often practiced in private since Spanish conquistadors initially forbade them. But Elliot and Erick hope their show can dispel suspicions and mistrust of the religion, which has surrounded the faith with a negative stigma.

“The Spanish found it comical that Yorubans were worshiping the saints so much more passionately than they were to God, like in Catholicism,” Elliot says. “They think something bad will happen to you like they’ll do voodoo or black magic on you, but I think we’re trying to show that Lucumí can honestly be a positive thing.”

By third grade, the brothers knew their involvement in both fashion and Santería would set them apart, but not always in a good way.

Bright yellow features pop against contrasting figures, resembling the Yoruban orisha, Oshun.

Photo courtesy of Spinello Projects

“We would go to third grade with an astrology book like weirdos, and people were like, ‘What are these people doing?’ Like we used to do the math to find people’s rising signs and sort of have a feel for who they are. It’s really based on the time, latitude, and longitude of where and when you were born,” Elliot says. “That determines where the planets were aligned or positioned, and then it’s spread into the chart.”

Growing up, their mom encouraged similar astrology rituals. Still, they credit much of their spiritual upbringing to their Afro-Cuban abuela, Norma Salgado, now 83, who practiced Lucumí and looked after the twins when their mom left.

“We didn’t have the easiest childhood, so when you’re in a situation like that, you kind of turn to faith to have something to believe in,” Elliot says. “Our mom considered herself atheist, but we would have to go out on certain full moons to collect energy and even go out when there were certain comets flying by.”

This powerful energy shines bright, quite literally, through each model’s glossy eyes. Using a manual photographic technique inspired by Cuban artist Belki Ayón, Elliot and Erick shot and layered multiple images to create deep contrasts in exposure.

One of the exhibit’s 14 pieces, titled Ibejí (meaning "divine twins" in Yoruba), embraces this technique as the brothers wear matching powerful black bodysuits with dainty white collar guards. This gender-ambiguous attire highlights a spectrum of energies and strengths unique to Lucumí saints throughout the show.

“Stories and practices will vary depending on the person practicing it,” Erick says. “So the techniques and emotion put into this are our visual interpretation of the religion, but of course, we invite everyone to come and understand it in their own way, and maybe even want to learn more."

“Entre Dos Mundos.” On view through Thursday, June 30, at Spinello Projects, 2930 NW Seventh Ave., Miami; spinelloprojects.com. Admission is free.