When Marco Rubio stood inside Miami's Freedom Tower in April 2015 to announce he was running for president, it seemed a little too on-the-nose that he immediately walked offstage and into the embrace of José "Pepe" Fanjul Sr., the billionaire sugar baron who has bankrolled much of Rubio's political career. The Fanjuls are arguably the most politically powerful family in Florida. Pepe Fanjul Sr. and his brother Alfonso "Alfy" Fanjul Jr. — estimated to be worth a combined $8 billion thanks to their ownership of Florida Crystals, the parent company of Domino Sugar — regularly rain political donations on Republicans and Democrats alike.

Now there appears to be yet another connection between Rubio and the Fanjul family, albeit one the politician doesn't want to discuss. A photo posted on Twitter by a Rubio staffer late last week reveals that the senator's latest crop of interns includes someone by the name of Pepe Fanjul. Though it's unclear which Pepe Fanjul that could refer to, Pepe Fanjul Sr. has an 18-year-old grandson named Jose Pepe "Peps" Fanjul III, who appears to be finishing his senior year at Deerfield Academy, a prestigious prep school in western Massachusetts.

Multiple staffers in Rubio's office did not respond to calls, text messages, and emails from New Times. Nor did Gaston Cantens, a longtime spokesman for Florida Crystals and the Fanjul family. Peps Fanjul himself did not respond to an email sent to his school email address.

But the photo raises a very simple question: Did Rubio hire the scion of one of his largest political donors — a family already accused of gaming politics to benefit itself — to work in his office? Rubio's camp had multiple days to provide an answer but chose not to respond.

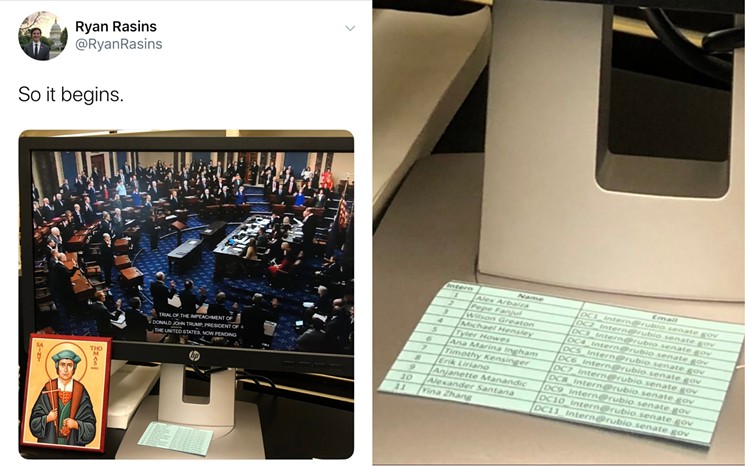

The photo was posted on Twitter by a young Rubio staffer named Ryan Rasins. He says online he worked as an intern in Rubio's D.C. office last summer before joining the team full-time in September. On LinkedIn, Rasins lists himself as a "legislative correspondent" in Rubio's office.

Last week, Rasins posted a photo of his computer monitor as he watched President Donald Trump's impeachment trial begin in the U.S. Senate chambers. But the photo also captured something else on Rasin's desk: a printout listing Rubio's interns. Of the 11 names, the second was Pepe Fanjul. Other interns on the list state online they work for Rubio's office. New Times messaged the email belonging to Pepe Fanjul — which has an "@rubio.senate.gov" address — but received no response. (The U.S. Senate Disbursement Office told New Times it does not keep records on unpaid interns working with lawmakers.)

Though no Rubio staffers responded to messages from New Times, Rasins made his public Twitter account private only minutes after New Times sent its initial email to Rubio's office. He also removed references to working for Rubio from his Twitter and Facebook bios.

The Fanjuls are among the most controversial businesspeople in the state. Alfy Jr. and Pepe Sr. come from a family of wealthy, sugar-mill-owning Spanish immigrants in Cuba but fled after Fidel Castro's 1959 revolution threatened family fortunes. They settled in Florida and built up their own sugar empire in the cane fields near Lake Okeechobee. The company now owns 155,000 acres in Palm Beach County alone and, in total, more acreage than all of Washington, D.C.

Environmentalists and government watchdogs have been critical of the family and the sugar industry at large. Excessive runoff of fertilizers and pesticides from sugar farming have been blamed for likely irreversible pollution in the Everglades, and two of the Fanjuls' major sugar giants — U.S. Sugar and the Sugar Cane Growers Cooperative of Florida — have fought attempts to force them to pay to clean up the Glades. Environmentalists also partly blame fertilizer runoff from sugar farming for foul-smelling toxic algae blooms that have flooded Florida beaches in recent years and endangered the state's largest industry, tourism.

As the New York Times' "1619 Project" noted last year, sugarcane farming has historically been one of the most exploitative and grueling types of farm work in the nation's history; much of the work used to be done by slaves. Since the Fanjuls rose to prominence in the '60s and '70s, the vast majority of cane farming has been carried out by easily exploited populations of immigrants. Lawsuits and critics have repeatedly accused the Fanjul Corporation of operating unsafe farms and deporting workers who complain — charges the company denies.

And the family could not have amassed such a vast fortune without help, subsidies, and outright corporate socialism from the federal government. A gigantic network of laws and subsidies — more than $2 billion per year — boosts the price of American sugar while tariffs keep cheaper sugar away from the U.S. market.

Even the conservative National Review in 2015 took a massive whack at Rubio for supporting the sugar subsidies because the Fanjuls have donated heavily to his campaigns. Those criticisms seem not to bother Rubio, who in a 2012 memoir stated he was proud to have had the Fanjuls host a Hamptons fundraiser for him over Labor Day weekend in 2010. In 2015, Pepe Fanjul Jr. and his wife Lourdes also hosted a fundraiser for Rubio at their home in West Palm Beach. Rubio has long said he's grateful for the family's support over the course of his career.

"The Fanjuls believed in me early on, when few others did, and I'm grateful for that," Rubio told the Treasure Coast Newspapers in 2016.

In fact, much of Rubio's rise traces to a spat between the Fanjuls and former Florida Gov. Charlie Crist. In 2008, Crist announced he wanted the state to buy back tens of thousands of acres of sugar farmland and turn the area into wetlands to help beat back pollution in the Everglades. Big Sugar companies, and the Fanjuls in particular, were pissed — and when Crist ran for U.S. Senate in 2010, the Fanjuls lavished money on Rubio's Senate campaign.

Since then, Rubio's policy platform has always aligned with that of the Fanjuls. Though he has consistently said the Fanjuls — and political donations in general — don't dictate his opinions, Rubio opposed a 2016 proposal to use federal and state money to buy back 60,000 acres of wetlands south of Lake Okeechobee, a plan that Big Sugar companies also opposed. Rubio's agenda has remained in line with that of sugar lobbyists even as other prominent Republicans, including anti-tax hawk Grover Norquist, have criticized his stance on sugar.

Now Rubio ought to answer if he has done the Fanjul family yet another favor.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]