In June 1979, during a break in Ted Bundy’s murder trial, Judge Edward Cowart walked into a room tangled with wires, screens, and TV lights five floors above his courtroom in the Miami Metropolitan Justice Building. “It was really something,” he said. “I thought I was in a space center.”

The building had been filled to the brim with media outlets from across the nation, all circling in to broadcast the trial of America’s most notorious serial killer. From the courtroom, cables carried pictures and sound up five floors to a room equipped with an expansive array of videotape-editing gear and more than 100 reporters, tape editors, producers, sound men, and camera operators. There were cameras in the courtroom and a film set in the courthouse.

The perpetual presence of TV cameras and news outlets presiding over the internal happenings of trials and proceedings is far from unusual today, 40 years after Bundy’s Miami trial for the murder of two Florida State University sorority members. But the presence of cameras in courtrooms did not begin to become legal until the late '70s. Bundy’s murder trial in Miami, one of the first nationally televised court cases in U.S. history, proved to be a watershed moment for the American justice system and the role the public would play in it. This trial, though frequently overlooked, stands as a precursor to other nationally broadcasted trials such as O.J. Simpson's in 1995.

It was May 1, 1979, when the Florida Supreme Court reached a unanimous decision authorizing the use of cameras and recording equipment in courtrooms across the state. The doctrine had been enacted after a year of public debate pertaining to the merits and potential disruptions that such a policy might create. The timing couldn’t have been better for the national media, which had already whipped itself into a frenzy over the Bundy trial, scheduled to take place in Miami just one month after the enactment of the law. America’s TV viewers had witnessed the murder of Lee Harvey Oswald, watched the blood and gore of the Vietnam War, and were now turning their eyes to another kind of real proto-reality TV: murder trials.

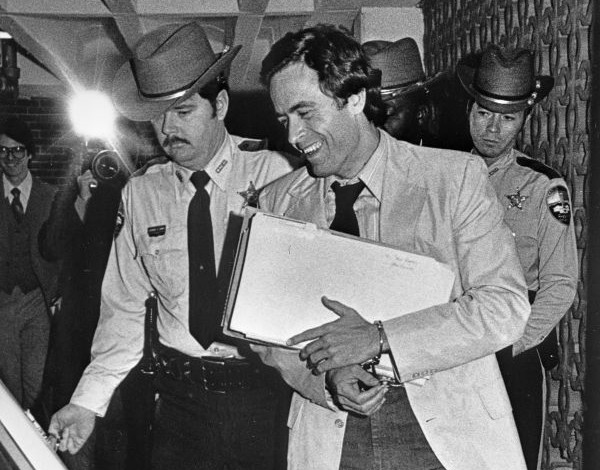

Bundy, a former law student who was suspected of brutally murdering dozens of young women, was not in favor of broadcasting the inner workings of his trial for public judgment. During the pretrial hearings, Bundy made a movement to restrict camera use in the courtroom and expressed his concerns of being tried “before the big eye.” The request was denied, and one of the United States’ first nationally televised court cases began in Miami June 11, 1979.

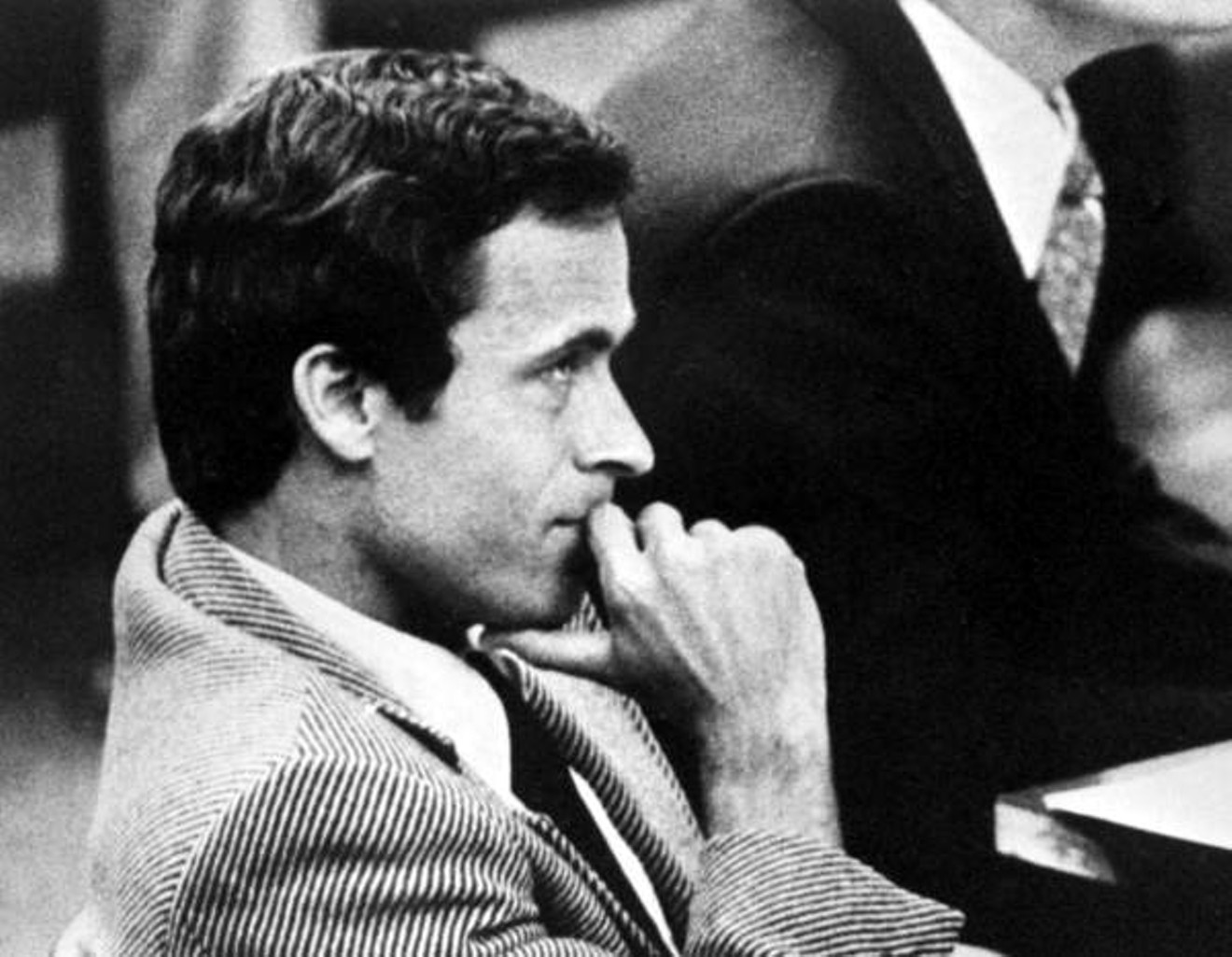

He found himself playing the lead actor in this nationally broadcast double-murder trial and adjusted to the spotlight with ease. Bundy, who in previous court appearances had looked rather wan and rumpled, was now dressing in nicely fitted suits with pressed shirts and matching ties. Bundy’s transformation was noticed by the judge, who commented, “I might say you look nice today, Mr. Bundy. I’m glad to see you in proper uniform.” When one of the public defenders was asked how the presence of cameras affected Bundy, he said, “He was very conscious of the camera. Every time something would happen where it would be logical to get a shot of him with the camera, he would look over at the camera and do his thing.”

Stage presence aside, the trial would result in Bundy being convicted of two murders, three counts of attempted first-degree murder, and two counts of burglary. He was given two death sentences, one for each of the Tallahassee murders. It was almost as if the convictions acted as a season finale for the American viewers who took the time to tune in. Ted Bundy's Miami trial would prove to be one of the catalysts in the birth of a new genre of both justice and television.

Today the true-crime genre lights up the imaginations of fans around the world. But before the podcasts and Netflix series, and before blockbuster movies cast unnecessarily attractive actors to play demented serial killers, there was a camera in a Miami courtroom.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]