"I cannot abandon Havana," muses Dr. Manolo Rodriguez over a cigarette in the opening pages of Robert Arellano's newest novel, Havana Libre. It is the summer of 1997—the height of Cuba's periodo especial, or special period of economic crisis after the fall of the Soviet Union. The second installment in Arellano's Cuba-centric series, came out earlier this month just ahead of the third anniversary of President Obama's decision to normalize diplomatic relations with Cuba after over fifty years of stalemate on December 17, 2014.

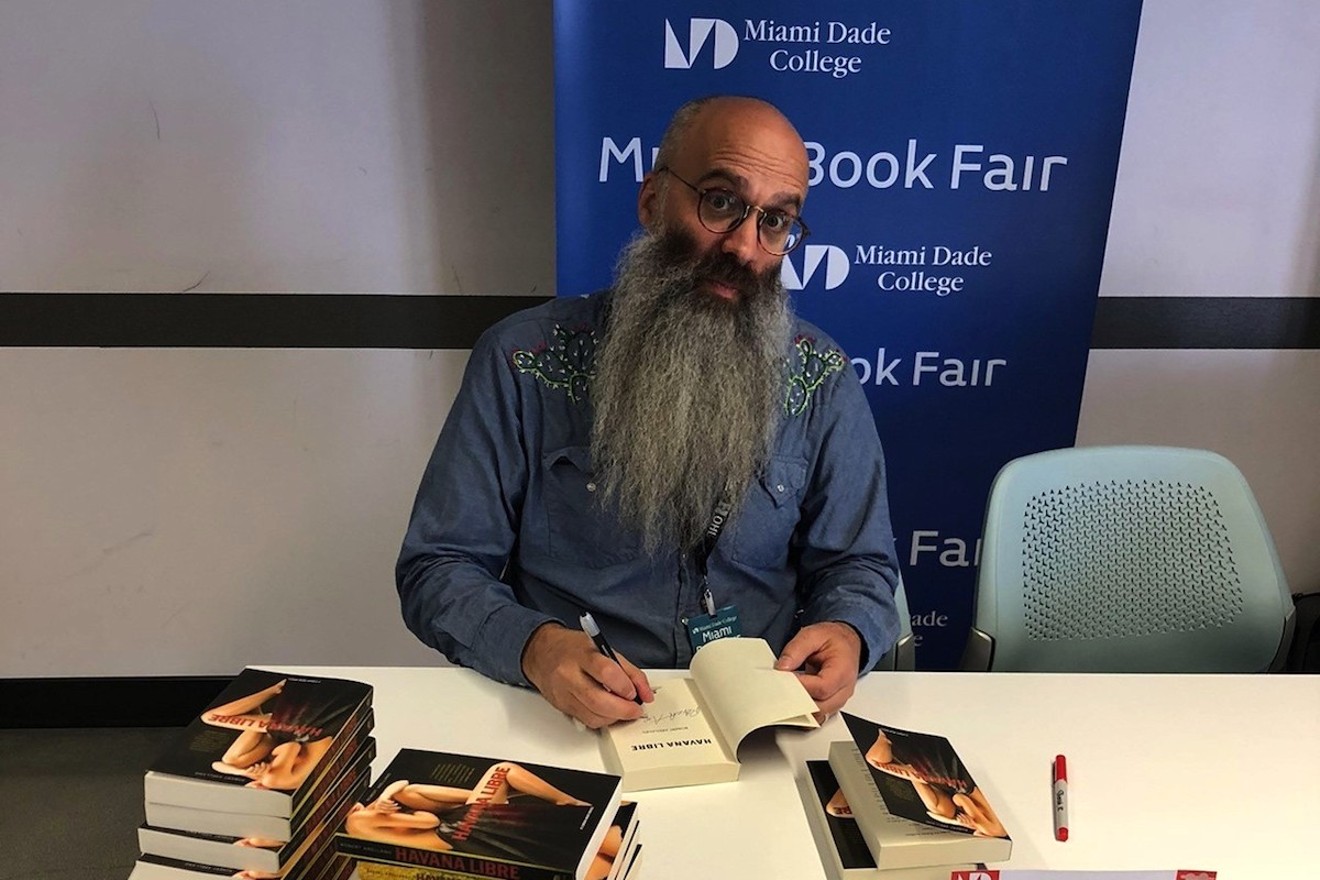

Cuban-American author Robert Arellano has built his most successful novels with Akashic Books at this painful intersection of ideology and experience that inform the lives of Cubans at home and in exile. His first novel, 2009's Havana Lunar, introduces the semi-autobiographical Mano Rodriguez as a refraction of what Arellano's life might have looked like had his family never left Cuba in the early '60s.

"I feel like a Miami Cuban, even though I was born in New Jersey," Arellano tells New Times. Born twenty minutes away from Union City, the second-largest Cuban enclave in the States, Arellano spent summers and winters in Miami with his parents, who eventually retired to Key Biscayne. "Every year, twice a year, my family would pile in the stationwagon, drive down I-95, and spend two, three, or more weeks with the family in Miami."

Like many Cubans of the exile generation, Arellano's parents vowed never to return to the island until the island's Communist government fell. In 1992, they were not pleased that Robert was planning to go to Cuba through a Brown student exchange trip, but eventually made their peace with the idea. "Brown made it possible for me to go back to Cuba," says Arellano, expressing a sentiment common to second-generation Cuban-America, who grew up hearing about the fabled island of their origin. "I say back because even though I was born in the States, it really felt like home for me on that first trip 25 years ago."

Five novels, a tenured faculty position at Southern Oregon University, and dozens of trips to Cuba later, Arellano remembers the fear and the exhilaration he felt as a 21-year-old getting to know Cuba for the first time. It is a wall that many second-generation millennial Cuban-Americans have broken for their families since Obama introduced the "people-to-people exchange."

Dr. Mano Rodriguez experiences this travel in reverse. Amidst the 1997 hotel bombings in Havana orchestrated by far-right Cuban exiles including the infamous Luis Posada Carriles, the young doctor is sent by the Cuban government to Miami to gather information about the men behind the bombings. His informant: Mano's estranged father.

Amidst the action, the quiet star of Havana Lunar and Havana Libre is Arellano's rich landscapes of daily life in Cuba during the special period, including blackouts, food shortages, the intricacies of conversation under an authoritarian government, and the craftiness of locals who offer guided tours to tourists for money — all details from over a decade of Arellano's journals from his trips in the '90s. And while the embargo and the Revolution have hardly budged since, Arellano reflects on the ways the island has evolved since, especially since President Obama's historic declaration three years ago.

"It has changed a lot," says Arellano. At places like the Fábrica de Arte nightclub, “it’s Cubans dancing with tourists," he says. "There’s not that sense of what I remember Cubans calling a ‘dollar apartheid’ in the ‘90s, where if you had dollars—and of course, now they have CUCs—you could get into places just for tourists, foreigners, and diplomats." He remembers visiting Cuba in the summer of 1997 with a moderate fear that his hotel or restaurant plan might be the target of a bombing.

"Now, it’s kind of shocking to me that Cuba has maintained some aspects of socialism while introducing opportunities for commercialism," he continues. "So there’s a sense of the apertura that, I think, Cubans really hoped would be stronger...is happening anyway, even though it’s been slowed and dragged down by the Trump administration," he says.

While he remains hopeful about the apertura, he criticizes Trump's Cuba policy — and especially his restriction of travel for people-to-people exchanges — as a regression not just to before Obama's announcement, but to thirty or forty years ago. “That’s democracy," Arellano says flatly. "People-to-people exchange is how it happens. If you’re a citizen of the democratic republic of the United States, and believe in the idea of people voting for their leaders, it’s actually at odds to maintain the embargo, because it’s not creating the conditions for democracy to occur."

Since his youth, Arellano has been acutely aware of the way many Cuban-Americans, especially in Miami, might perceive him or his work as traitorous to the exile community, having planned an event like 2000's Rock the Blockade concert in Havana. He admits romanticizing the ideals of the Revolution in his youth, and his friend, fellow Cuban-American author Achy Obejas, "holding a mirror up to him" seven years ago to remind him of the "kneejerk justice" of state-sponsored corruption and murder.

While Arellano remains ardently against the embargo, fatherhood has also put his parents' exile into sobering perspective. "Now that I’m a dad, I have every day since my kids were born been more aware of the sacrifices my father and mother made for us, and also, of what they lost," he says. "I’ve learned that their exile is as much a tragedy of the Cold War as it is of the Revolution.”

"Río para no llorar," he laughs. I laugh to keep from crying.

Arellano might still be seen as radical by the Cuban-American community, but hopes the apertura can provide an opening in Miami, too — for discussion and understanding. He hopes his work reaches the many Cuban-Americans that find themselves "somewhere in between" — that believe the embargo is no longer a viable option, but remain critical of Cuba's treatment of dissidents and lack of economic mobility. For second- and third-generation Cubans-Americans, he adds, "this is your patria, too."

Despite the conflict and violence between the two governments and its agents over the decades, the Cuban people of the island have continued to create livelihoods, resolviendo among themselves for solutions to everyday problems and finding joy all the while. Arellano remembers the words of a taxi driver on his first trip to the island back in 1992.

"Mira," the driver told Robert. "I have a message for you to take with you. Tell the Americans that this thing between the governments is something else. That is between the governments. The Cuban people love Americans very much; we love your music, we love your culture," Robert remembers the driver saying, the old fears dissipating.

"One day, when this fiasco between the governments is done, we are going to have a tremenda pachanga.”

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]