Even before Nicholas Griffin moved to Miami, he knew he wanted to write about it. Born in London and a New Yorker since the late 1980s, the novelist and nonfiction author decided to relocate to Miami in 2013 with his wife and two children.

“I just sort of looked around and realized that there was nowhere else like this in America,” Griffin tells New Times. “In other American cities, the normal immigrant populations get absorbed and everyone becomes more or less the same kind of American. But down here, that hasn’t happened. We’re still a majority foreign-speaking population down here.”

Griffin, the author of more than a half-dozen books that range from historical fiction (Dizzy City, about the First World War) to sports-themed nonfiction (Ping-Pong Diplomacy, about the role of table tennis in international affairs), initially considered addressing Miami through a wide lens.

“The original book that I pitched was actually a much broader book,” he says. “I was looking at the period from 1980 to 1985, and how some of the stories that started in Miami then began to spread out across the country.”

Publishers were not immediately enthusiastic.

“It was a good idea, but a diffuse one,” he says, “and no one would touch it with a bargepole.”

Still, Griffin moved forward. “If you’ve got a good idea, you’ve got to follow it,” he says. “So I started doing my research anyway.”

Beginning at the beginning of the decade, he quickly ran into the growing cocaine trade, the Mariel Boatlift, and the riots that followed the acquittal of four white officers who beat a black motorist, Arthur McDuffie, to death.

“What I found was I just couldn’t get out of 1980. I was like, Oh, my God, I could actually tell this whole story without ever leaving one year.”

The result is The Year of Dangerous Days: Riots, Refugees, and Cocaine in Miami 1980 (Simon & Schuster), a portrait of Miami that captures the tumult, the tension, and the strange exhilaration of that year through a detailed recounting of those three watershed events.

Just as it tells the story of the city through three main subplots, the book focuses on a few key figures, some of whom will be known to longtime Miami residents (then-State Attorney Janet Reno, the veteran Miami Herald crime reporter Edna Buchanan), some of whom may not be (an almost nonchalant Colombian hitman named Anibal Jaramillo, a homicide investigator named Marshall Frank).

Griffin began his research in old newspapers.

“I thought I’d just take a few weeks going through periodicals online,” he says. “But of course the Herald hasn’t digitized anything past 1982, so it actually took me over a year inside libraries, going through microfiche like it was 1955. And I didn’t just read the Herald. I read every newspaper published, to really try and get this 3-D picture. The fascinating thing about Miami is you’ve got newspapers that represent different races in Miami. So you can read what the black newspaper is saying, and it’s like you’re reading about a different city, and then you move across into the Spanish-language papers, and again, you’ve changed cities, and yet, in theory, we’re still in Miami.”

From there he moved outward to books (“I read about everything from Cuban history to Miami history”) and then went in search of the real people who helped build the city. “I got to maybe 60 or 70 of them,” he says.

In the welter of interviews, Griffin had one favorite.

“The guy who sort of saw it all from 10,000 feet was Maurice Ferré, the old mayor,” he says. “He won office six times. He knew his stuff.”

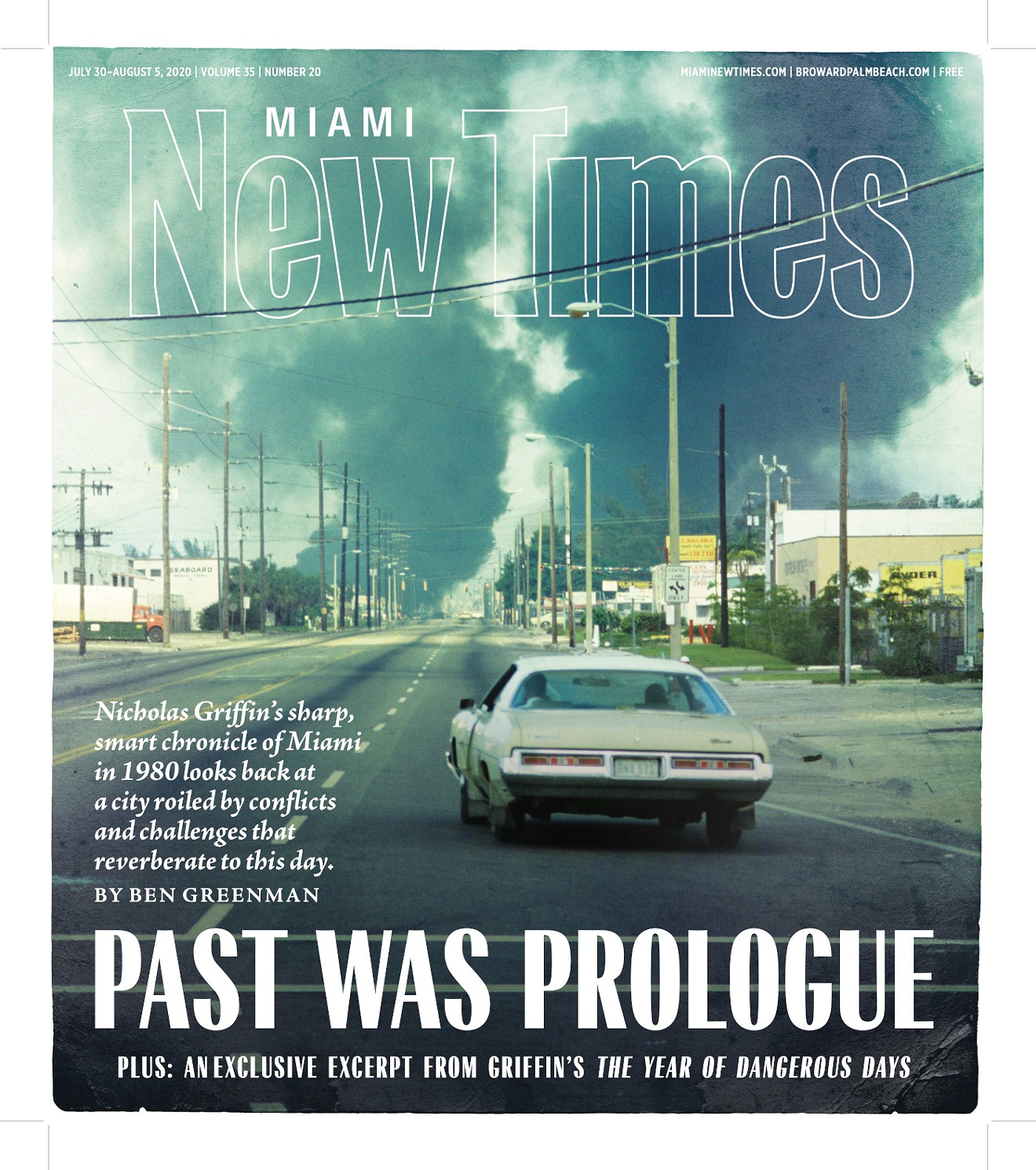

Street scene of burning building with police and firefighter responders during the McDuffie Riots, 1980. Liberty City.

Photo courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum/Miami News Collection

“It was great to walk through the decades with him because he and his family had been involved here for so long. If you pick one figure who really had this huge influence on where Miami should be looking to grow, it was Maurice Ferré. We could have just been another smallish city tacked on to the far edge of America, trying to become sort of some sort of shadow of Atlanta or New Orleans.”

But Ferré had a different perspective. “He was one of those guys who said, ‘No — look at a different map. Don’t look at the American map, look at an international map.’ Then you can see that Miami actually looks like it’s in the middle of everything. If you look at America, together with South America and Central America and the Caribbean, Miami becomes central. I think that was a huge gift that he gave and then drove forward for Miami.”

"Miami Was the Biopsy"

Ferré’s insight helped Griffin to understand one of Miami’s central characteristics: its apparent indifference to its image.“I think the key for Miami is that we’ve never been that concerned with what the rest of America thinks of us,” he says. “We know that the New Yorks and the Atlantas kind of look down on us, and that’s okay with us. Because Miami’s secret strength is that we’re seen as this great important city outside of America but not necessarily inside. If you’re you’re born in Central America or South America, and there’s unsteadiness or something revolutionary happening in your institutions, where do you move your money to? You move it to Miami. Where do move your family to? You move it to Miami. So even when this has been a very shaky city from a domestic vantage point, it’s still had that great international capital.”

Griffin says he worked hard to ensconce himself in the past while he was writing. “I really try hard to let the facts speak for themselves. Even the language I’m using, I wanted it to reflect 1980,” he says. “I didn’t want to be persuaded by my own political opinions in 2020.”

But as he writes in his book, “If 1980 was a diagnostic test for America, Miami was the biopsy.” And many of the issues of the time have since metastasized, especially during the Trump era. The boatlift (and discomfort around immigrants) has evolved into the wall. The drug trade remains, both in the form of Mexican cartels and the more recent plague of opiates. And questions of police brutality and institutional racism have defined much of 2020.

At times, past was prologue in the most explicit ways.

“In the wake of the McDuffie case,” Griffin says, “there was a real sense in Miami’s African-American community that they had been passed over by justice. And that was under Janet Reno, who we came to think of as this really liberal figure. But that’s not who she is in 1980, when she is accused outright of racism by the black community.”

The issue has resurfaced pointedly in recent months, as Katherine Fernandez Rundle — who took over when Reno went to Washington in 1993 — vies for an eighth term as Miami-Dade County’s state attorney. A career of tough-on-crime hawkishness coupled with a reluctance to bring charges against police officers in on-duty shootings has generated significant opposition leading up to the upcoming August 18 contest. Rundle’s opponent in the Democrat-only race is Melba Pearson, an assistant under Rundle for 16 years who left the agency to serve as deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida. (Rundle herself served as an assistant under Reno for 15 years.)

Current events, of course, are unfurling in the fog of a pandemic. (Griffin himself contracted COVID-19 back in March — “I think I was one of the first hundred or so in Dade County with it,” he says.)

But the author of The Year of Dangerous Days is guardedly optimistic that Miami can avoid reactionary thinking moving forward.

“Whether you’re looking at Black Lives Matter or anything else in Florida in 2020, we haven’t had huge outbreaks of violence,” he says. “If Trump can convince you that law and order is absolutely central to you keeping hold of your life and your property, then you’ll probably swing his way. But I think Miami — we haven’t had that sort of immediate threat down here. So I don’t think anyone’s going to be tricked or blinded by that.

“And my guess is Miami will swing towards some change.”

Read an excerpt from Miami author Nicholas Griffin's new book, The Year of Dangerous Days, here.