Judy Chicago, on the other hand, laughs easily. She wears dangling blue earrings and affectionately introduces her husband. She’s the literal prototype for the feminist artist, having founded the first feminist art program in the United States in 1971. And though she has continued to work and develop as an artist and teacher over the past 40-plus years, many things have remained disturbingly similar to the landscape in which she began creating.

“We’ve been here before,” Chicago reflects after showing an image from her Instagram page — a Bustle magazine montage of Lindsey Graham, Brett Kavanaugh, and Chuck Grassley juxtaposed with Three Faces of Man from her series Power Play, painted in the mid-'80s. “I see that and think how sad it is that my paintings from 30 years ago are so relevant.”

Chicago finished her most famous work, The Dinner Party, in 1979. It gained international acclaim for its ambition to display a female-centered history of Western civilization. Mockups and test sculptures from that installation will be part of the exhibition “Judy Chicago: A Reckoning” at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. Everything on display — work spanning three decades — touches on some aspect of gender even when it doesn’t mean to. Associate curator Stephanie Seidel explains that the goal of the survey is to show the range within Chicago’s career. But even in discussions of her early minimalism, allegedly made before her work "became feminist," gender seems to seep into the conversation.

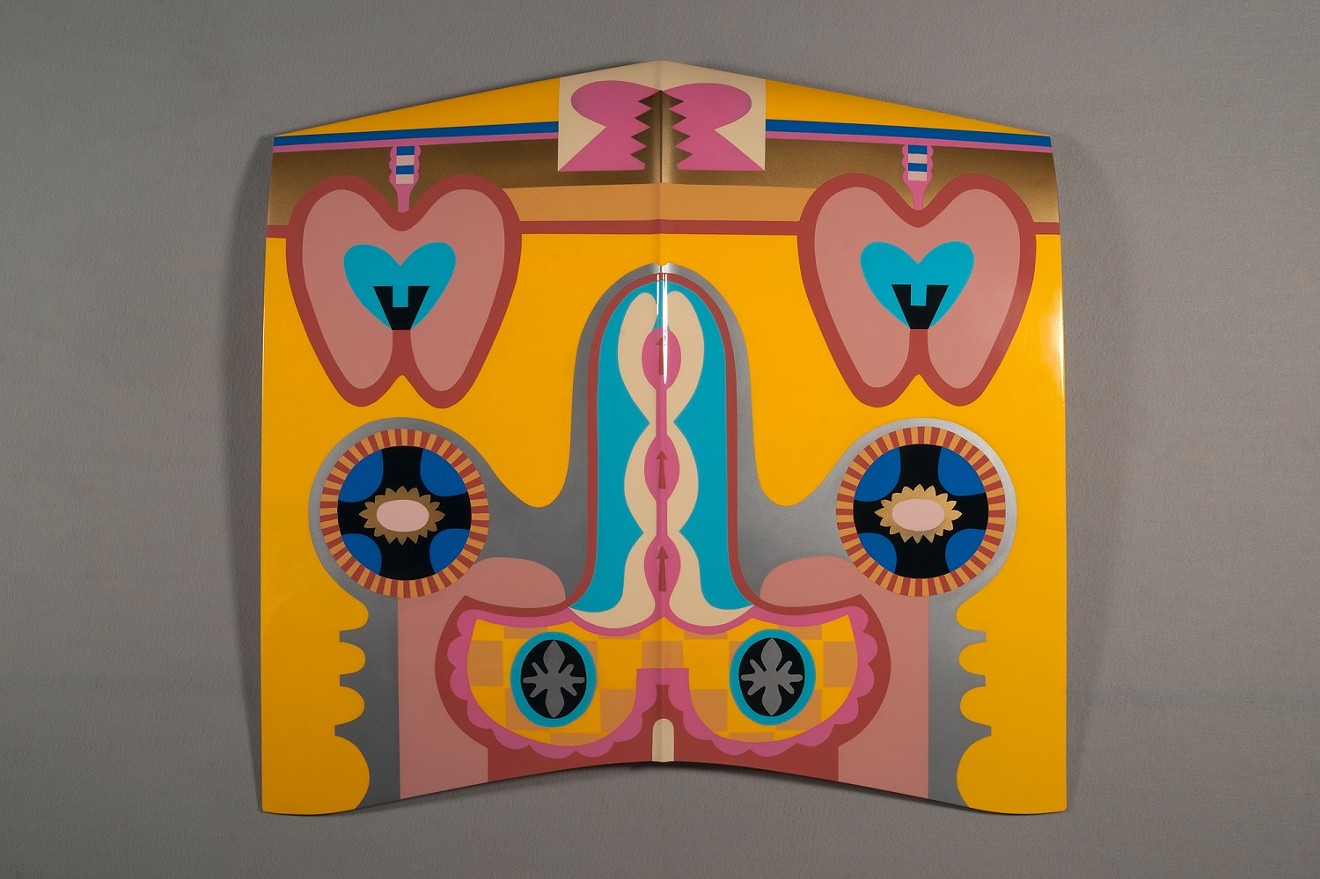

“She picks colors on a spectrum that are not part of a typical art palette,” Seidel says. “Also, the shapes Judy creates with these techniques are very different and distinct. That’s not specifically feminine,” she explains — but it’s difficult not to see the dreamy colors of Sunset Squares or the luscious curves of Bigamy Hood as representing a kind of resistance.

Judy Chicago, Sunset Squares, 1965, 2018.

Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, New York. Photo Fredrik Nilsen Studio

Many women can recognize “A Reckoning” as a survey of not only a woman’s work but also the process of navigating worlds that were never meant for you. Aside from day-to-day misogyny, minimalist art was almost exclusively a boys' club in the mid-'60s. And though we might have visions of Audrey Hepburn and Twiggy, women in the United States were still largely relegated to housewifery until the late '70s.

“Judy went to pyrotechnic school as one of the only women. She went to auto body school as one of the only women,” Seidel says. “She did not just want to contribute to an art system the way it was running, but... create new images, create new production techniques, create new means of collaboration with volunteers, create new systems of distribution.”

Quoting Chicago from a 1974 interview, she adds, “‘You do not get brownie points for telling men to fuck off.’”

Today we can take for granted that there are empowering spaces carved out exclusively for women. We take for granted that someone as mainstream as Beyoncé can stand onstage with the word "feminist" emblazoned behind her, and maybe we take for granted that that spectacle feels a bit passé now. We’ve reached a strange dissonance in our society where so many people appear to cherish and value women’s humanity while at the same time devaluing their work and experiences.

This is why Chicago’s work remains so relevant — she isn’t just looking at gender constructs; she’s working them. Her labor involves the appropriation and transformation of presumably masculine tools — car hoods, fire, and smoke — but she also takes devalued so-called feminine labor and honors it.

We live in a world that still dismisses certain jobs because they're associated with women — simply ask a domestic worker, nurse, garment worker, or mother. For her book The Birth Project, Chicago couples so-called women’s work, specifically embroidery, with visceral imagery of childbirth. The result creates a double juxtaposition: On the one hand, the often-romanticized process of giving birth is brought down to its physical reality, while the labor of needlework, dismissed as the pastime of grandmothers, is elevated to the highest recognition of fine art.

Or take, for instance, The Dinner Party, referencing not only the feminized labor of home cooking but also flower and table arrangement and the maintenance of domestic spaces. Dinner parties are literally the backdrop or afterthought of real, important work and are seen as frivolous at best, irritatingly irrelevant at worst. Yet Chicago sets The Dinner Party as the stage for the incredible burden of "that cycle of repetition and erasure": women’s history.

Of course, all you have to do to understand the weight of women’s labor is to be in the kitchen on Thanksgiving or be a teenage girl having her first period with a single dad. Most daughters already understand it.

"The problem is that a lot of women of my generation and subsequent generations were more willing and determined to raise strong daughters than to help their sons find new ways to be as men," Chicago says. “And so young women are stranded... because men have not changed. Men have to change too. And how to accomplish that? That’s a big question right now.”

Maybe it seems frivolous, but perhaps the change begins by teaching men to appreciate work like Judy Chicago’s.

"Judy Chicago: A Reckoning." Tuesday, December 4, through April 21, 2019, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, 61 NE 41st St., Miami; 305-901-5272; icamiami.org. Admission is free.