Holshouser's aerie is reachable only via an aluminum ladder at the far end of the curved bar that leads up to a short, low-ceilinged catwalk, across which one must scuttle stooped over. Posted next to the ladder is a foot-high red-on-white placard, one of those gimmicky takeoffs designed to resemble a "No Parking" sign. "SOUND GOD AT WORK," this one reads. "ENTER AT YOUR OWN RISK."

When Holshouser bothers to stand up, which he does occasionally, he can see the stark room in which a few hundred of Lara's closest fans, the young women in particular, sway to the music like sawgrass in a concrete swamp. But mostly his eyes flicker between the singer and the mixing console, which dictates the volume and texture of the body-throbbing din that flows through the Talkhouse's floor-mounted subwoofers and EAW speakers suspended from the ceiling high above the stage. From left to right, each identical-looking row of controls in front of him corresponds to a microphone on the stage. The one pressed up close to David Goodstein's kick-drum. The one that sprouts from bassist Phil McArthur's amplifier. The one connected to Nil Lara's ukulelelike tres. The one in front of Lara's contorted face. Et cetera. On a strip of masking tape that runs the length of the console, Holshouser has magic-markered a shorthand notation of which mike goes with which row. Similar masking-tape reminders of past performances Holshouser has sound-engineered adhere to the booth's low ceiling, their ends dangling like stalactites.

Hundreds and hundreds of them.

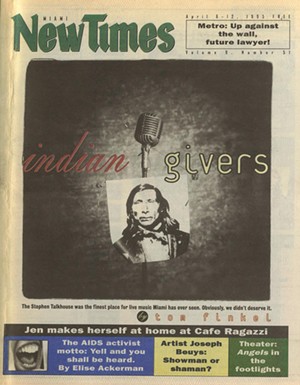

For the past two and a half years, the Talkhouse has served as one of South Florida's most abundant musical resources, supplying the area's cultural cognoscenti with a constant flow of pre-eminent acts, national and local, well-known and obscure. Guitar virtuosi Leo Kottke and Richard Thompson. The unrivaled lord of laid-back, J.J. Cale. Lucinda Williams. Koko Taylor (200 pounds of lame-encased funk). Folk hero Richie Havens. Local hero Nil Lara. Natural Causes. Taj Mahal. Warren Zevon, Greg Brown, Ani DiFranco. The Radiators. Mary Karlzen. Aquarium Rescue Unit and Bare Naked Ladies. Vassar Clements, Trout Fishing in America. Donovan. Diane Ward. Holly Near. Boukman Eksperyans. Leon Russell. Terrance Simien and the Mallet Playboys. Joan Osborne. And from his little cloister littered with cassette tapes and empty Budweiser bottles, the Sound God has presided over nearly all of them. Look up and you could, if you were a mixing-console junkie, pinpoint the knob Holshouser twiddled to raise Joe Ely's trembling honky-tonk howl a whisker, or to mute the fuzz in Jorma Kaukonen's twelve-string guitar.

Next Sunday night, April 16, the Sound God will clamber up here as usual, flip on his Soundtracs mixing console and his Rane equalizer, his two reverbs (one made by Yamaha, the other by Alesis). His two sound compressors, also by Alesis. His system compressor. His BSS crossover and his Rane crossover. Nil Lara and his band will take the stage at about eleven o'clock, as they did this night. They will probably play two long sets with a break in between. Fifteen or twenty songs — several hours' worth in Lara-time. Spent and sweating, they'll finally close the place down at about four in the morning.

After which the Stephen Talkhouse will cease to exist. And for any Miamian with the slightest ounce of passion for live music performed in a saloon setting, the loss of the Talkhouse is an unmitigated, unparalleled one, a goddamn shame.

A seven-year veteran of the trade, Peter Honerkamp finds himself looking at the music-club business from the far side of 40, though just barely. Born and raised in the borough of Queens, he has worked as a tennis pro and a journalist, putting in a three-year stint at the New York Post. In 1987, flat broke, having used up most of the decade living in Spain and writing what he describes as "a 1700-page shitty novel" — unpublished — he persuaded his relatives and in-laws to invest and bought a bar in Amagansett, New York, amid that enclave of astronomical discretionary income known as the Hamptons. The space, a converted nineteenth-century house, had been redone as a bar in the early Seventies. Honerkamp and his partners decorated Spartanly, kept the name of the establishment's earlier incarnation (the last king of the Montauk Indians, Stephen Talkhouse was a Long Island native), and began serving drinks and booking bands.

The concept — bringing in national acts to play for capacity crowds of about 100 — was well-received, and during the summers, when the well-to-do took their pleasure in the Hamptons, it was more than acceptably lucrative. During the off-season the bar battened down with mostly local musicians, tailing off significantly in attendance but managing to retain a respectable coterie of loyal year-rounders.

The club's success was gratifying, but it was seasonal. "I started thinking, why not do something in a warmer climate?" says Honerkamp, whose first thought was to open a wintertime branch in Key West. "I'd been down in Key West in the early Seventies, but it seemed like it would be really hard to get an act to travel all the way down there, and besides, the place wasn't the same as I'd remembered it. But I passed through South Beach in 1989 and really liked it."

In March 1992, Honerkamp and 32 fellow investors paid $485,000 for a two-story building on Collins Avenue, just north of the alley that passes for Sixth Street, in a not especially sparkling stretch of South Beach. They spent hundreds of thousands of additional dollars to transform the structure into a bar that was starkly decorated — a long, wood-topped bar, a glass-fronted cooler stocked with beer, a few dozen scarred wooden tables, and, flanking the stage, a mural of couples dancing — but acoustically enviable. "The place was a crackhouse when we bought it," recalls partner Loren Gallo, a friend of Honerkamp since kindergarten. A compact man with a rectangular face and piercing hazel eyes, Gallo was an engineering consultant before switching careers to club-ownership. He owns a piece of the Amagansett Talkhouse and was one of about a half-dozen of the group of 33 who sank sizable amounts into the subtropical offshoot, which he took charge of renovating for music. He had spent time in Miami during the Eighties while working on the Metrorail project, and moved to Miami Beach to head the new Talkhouse staff. (Honerkamp's plan, which he stuck to for the first two years, was to maintain his house on Long Island and relocate to Miami Beach with his family for the season here; during the winter of '94-'95, he made only occasional forays south.) "We were considered pioneers on lower Collins," Gallo says.

The Talkhouse opened in July 1992 to scanty summertime crowds, and then to Hurricane Andrew, which closed down the club for a short while. The owners subsequently added a patio bar in back, semi-open to the outdoors. Storm damage aside, however, the enterprise struggled from the very start.

"We were always undercapitalized," Peter Honerkamp says. "Our initial thing was that if we brought a lot of our friends in, a lot of the people who'd played at the club in Amagansett who nobody else was bringing down here, we'd be able to establish ourselves."

For the owners, importing the Talkhouse modus operandi involved a lot of money, above and beyond fixing up the club. A key component was the logistical phenomenon known in the music business as "routing," a nightmare with which Loren Gallo says he quickly became all too intimately acquainted. "Sometimes it was more expensive to get a band here than to get them to play in New York," Gallo explains, owing to Miami's geographical isolation. "From Atlanta, it's much easier to go to New Orleans or Austin." Balanced against the bigger investment required to induce bands to travel to South Florida was the Miami Beach Talkhouse's capacity, more than twice that of the Amagansett club. A bigger room meant tickets could be sold at lower prices — shows in Amagansett sell out at $40 or more per head; the asking price here tended to be in the $20 range — but it also meant the proprietors had to count on more people to fill the seats and pay the bills.

The bands came, all right. The audiences didn't.

When they failed to sell out, the owners gave away tickets, reasoning that a full house was better than a vacant one, no matter how it was accomplished. "The people who are doing culture here — Miami Light, Tigertail, Cultura del Lobo — we presented with all of them," says Gallo. "Those people do a lot of shows, but they're nonprofit organizations. If the Talkhouse was a nonprofit and got NEA support, it would be great."

Adds Honerkamp: "You start running out to your dentist, to the club where you work out. I'd give out hundreds of tickets. One of the illusions about a music bar, you could be losing three grand on a given night and the place is packed. Anyone who looks in would say, 'The guy's raking it in,' and you're losing your shirt.

"Leo Kottke? Leo Kottke lost money," Honerkamp goes on, reciting a catechism of futility. "Holly Near? We lost a fortune on Holly Near. We got killed on the Mavericks over New Year's in '93-94. Buster Poindexter. Jorma Kaukonen. Jefferson Starship. We got killed on Warren Zevon at first. We lost on G.E. Smith. Lucinda Williams and Joe Ely? We lost money on that."

"Nothing has any enduring power in South Florida. If you get a couple of years out of a business, you sell it," says Tom Bellucci, a man who knows a little about the vagaries of this area: After getting a couple of years out of his own business here, he sold it.

In 1988 Bellucci opened the Island Club at the corner of Washington Avenue and Seventh Street, hoping to satisfy what he perceived to be a demand for a neighborhood bar that was both upscale and no-frills. By the time he sold the place four years later, he had tried everything from food service to DJs to local bands: Nil Lara played the Island Club, as did the pre-major label Mavericks; Natural Causes was the bar's house band. "It's a strange market, a much, much more treacherous market than I've ever seen," says Bellucci, a widely traveled New Yorker whose acquaintance with Peter Honerkamp goes back to Queens. "In New York, you do it right and you'll succeed. Quality doesn't work down here. I can't tell you the look of amazement on [Honerkamp's and Gallo's] faces when something didn't work out or people didn't show up. I could only tell them, 'That's Miami.' The people here are extremely fickle, they don't make plans till the last minute. Maybe we could say this about society A they refuse to commit to anything. It's the only place I've ever been where you can throw a party and people won't show up just because there's something else to do."

Practical recognition of that volatile element came late to Patrick Gleber. Not coincidentally, it was the Stephen Talkhouse that spurred a change in the way Gleber did business. Along with partner Kevin Rusk, Gleber owns the only truly legendary live-music bar in Dade, Tobacco Road. Although Tobacco Road is several miles removed from the Talkhouse geographically, and also somewhat distant in terms of the sorts of acts that play the club (the Road is known almost exclusively as a blues bar), certain bands overlapped. And with both a bigger budget and a bigger room, the Talkhouse could lure just about any artist who previously would have been counted on to play the Road. That didn't faze the owners of the smaller bar.

"It made us think more about the business," Gleber says. "Entertainment focus used to make up 75 percent of our thinking, because for us the weekend was that big. Now it's maybe 25 percent — still a significant part, but we don't make money on the entertainment."

When Tobacco Road books a band to play its tiny upstairs stage, the bar charges six dollars for admission. ("It used to be five bucks," Gleber notes. "When we raised it a dollar, people were flipping.") Even when coupled with the money taken in for drinks during the show, that revenue falls short of a profit, when the costs of booking artists — the band's fee, accommodations, advertising for the performance — have been deducted.

"But we've gotta do it," Gleber says. "It's what the Road is known for, and the shows are great. And I can keep it going because my business during the day and on the evenings during the week has significantly improved. When the Talkhouse opened, I realized my business was gonna go down more than it already had. So I said, 'Let's start looking at Tobacco Road another way.' Our house band, Iko-Iko, had always performed downstairs. We moved them up to the top floor. The music is now all upstairs, we're doing much more food business on Fridays and Saturdays, and we're focusing on happy hour and late-night dinner specials."

Though he readily acknowledges that the Talkhouse beat him out for some bands, Gleber says he's sorry to see the club close. "They put on amazing shows. Whenever I'd go there, I'd look around and say, 'They can't survive doing this.' But it's Miami's loss."

Former Island Club owner Tom Bellucci shares one significant thing in common with the owners of the Talkhouse. They bought their buildings before going into business. For Bellucci the boom in South Beach real estate allowed him to sell at a slight profit. For himself and his partners, says Loren Gallo, the Talkhouse's pending sale will result in a loss. He won't comment about it further except to say, "If we hadn't bought the building, we'd have bailed two years ago."

Bellucci believes Miami Beach government should bear some of the blame for its spectacular legacy of fortune and failure, one that dates all the way back to Carl Fisher and John Collins, for whom an island and an avenue, respectively, are named. "I don't think the city realizes that bringing in more and more stuff isn't so good," Bellucci says. "I would never start a business here again, it's not worth it when you've got to devote such a large percentage of your energy to fight the city on nitpicky shit. If an inspector is overseeing a job and he gives you the go-ahead, and another inspector comes in later and says, 'No, you've got to do it this way,' you have no choice but to change it. And there's a very low dollar ceiling above which you have to get a permit. It's just a maze of regulations where they can come down on you if they want to. They're not user-friendly. And it's not like that in other parts of the country — there can be a different mentality about helping people foster business."

As it stands, the Beach comprises very little of the sort of institutional knowledge that makes success possible in the long term. "When people come here to do business and it doesn't work out, they leave," Bellucci comments. "The city needs to reach some sort of consensus that there's going to be a community here. With all the new construction, they should set up some sort of board where small businesses could come and give feedback, where you don't just have a summons that comes down on you like a time bomb. Some people are wrong, sure, but a lot of people have legitimate beefs. As it is, new people will come in, they'll trip over the same things, and no one's there to help to change it, no one with stories of the problems they had. They go back over the causeway with their pockets empty, and they never come back. It's a bad dream."

In attempting to outline why the Stephen Talkhouse failed in Miami Beach, Peter Honerkamp's musings orbit insistently around two points: One, he honestly does not know exactly what went wrong. Two, no matter how dim a view he takes of South Beach — and that view is mighty dim — he is not bitter about his experience here and doesn't take the outcome personally.

"If I had it to do all over again, I would have made the front room warmer, made it feel more like a bar and less like a vacant room. I think one of the problems we had was that we weren't able to just have a bar that has music. We never made it as a bar," Honerkamp says, acknowledging that even when the Talkhouse filled for a concert, showgoers tended to bolt for the doors as soon as the band left the stage. "I'd have tried sooner to take that back space and make it accessible from the alley. At the Talkhouse in New York, you don't have to pay to come into the bar A it's a separate room. But [here] the alley was a disaster, and the City of Miami Beach didn't pay any attention to us. We could never get them to move the bums. They'd break in and steal liquor, urinate on the walls." Repeated calls to police netted the Talkhouse a hefty log of complaints, but little else. "I'm no expert, but it did seem to me there was some favoritism there, that if we were prominent celebrities that wouldn't have happened," Honerkamp theorizes.

In booking bands, the club made a special effort to be inclusive. For the so-called Woodstock generation, there was Richie Havens, Joan Baez. New-music devotees were offered acts such as Bare Naked Ladies, John Wesley Harding, Joan Osborne. The Haitian combo Boukman Eksperyans played the Talkhouse. Mario Bauza did, too. And Cachao. And Holly Near, a proven draw in the gay community. "But we should have done more legwork on what was happening locally," Honerkamp says. "We should have focused more on local people. It wasn't through New York City arrogance, though. We thought we could establish ourselves first with national acts."

While Honerkamp and Gallo are reluctant to attach blame, both cite the Miami Herald's refusal to tout their shows as a factor in the Talkhouse's inability to reach its intended audience. ("I don't think there's anything to be gained about criticizing the lack of coverage — it's our responsibility to get the word out," is the way Gallo puts it.) And anyone who wonders why the club never invested in radio advertising probably hasn't lived here long enough to know the reason: Local radio stinks. To put it another way, no single radio station in town appealed to the Talkhouse's market — intelligent people of legal drinking age. Gallo did, in fact, underwrite programming on WLRN-FM and WDNA-FM, but that hardly qualifies as a radio blitz.

One of the most common avenues for criticism leveled at any club that opens in Miami Beach has to do with the owners' place of origin, particularly if that place happens to be New York. Arthur Barron knows this well, being both a club owner and a New Yorker. His Washington Avenue bar Rose's, which he runs with his wife Charlotte, bears a spiritual resemblance to Tom Bellucci's defunct Island Club. "I never felt as though Gallo and Honerkamp were really cut out to do business in Miami Beach," Barron remarks. "They brought their Long Island attitude toward the music business to Miami Beach and never really adapted to the environment. They had a certain attitude, they were not going to be flexible, and I think they never really recovered from that."

That Barron has adapted to the environment here is a testament to his tenacity, if not to Oscar Wilde's observation that "Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes." A half-dozen years before opening Rose's in 1993, he presided over an Ocean Drive jazz supper club called Tropics International, whose plummet into bankruptcy after Barron's 1989 departure embodied all that could go wrong in South Beach's ascendance to resort-heaven status. (The club's ill fortunes were chronicled in these pages in the June 1992 cover story "The Cancer of Tropics.")

This time, Barron vows, he has made certain he'll be on for the long haul. "Our primary interest in opening up a music venue was to go into something as a longevity factor. We weren't interested in making a killing, we were interested in staying in business." He doesn't charge a cover for the local bands he books, he points out.

Local bands, however, don't seem to be any guarantee of success in themselves. "Nil Lara played Thursdays at the Island Club for a whole summer," notes Tom Bellucci. "And nobody showed up. People hadn't been programmed to appreciate them yet. If they had good taste, they'd rather subordinate it to go where the herd goes."

Barron is equally blunt in assessing the area's taste for live performance in general. Mentioning the recent ill-attended Lincoln Theatre appearance of Jerry Gonzalez and the Fort Apache Band — a Grammy-nominated Latin combo that sold out the Lincoln Center in New York — Barron adds, "Why won't people come out and support live music? I think a lot of the populace here doesn't want to sit still for an hour and a half and pay attention to the cultural aspect of a Richie Havens, a Taj Mahal. People can't appreciate how good a thing is until it's gone. We seem to have an apathetic community here."

Pathetic might be a better word. More than anything else, Peter Honerkamp has come to believe, South Beach's nightclub scene, which revolves around a glorification of the superficial, was all wrong for the kind of bar he wanted to run. "I don't want to come across as a bitter New Yorker; we came down to be part of Florida, part of Miami Beach." Having said that, he adds, "I think South Beach is the most emotionally retarded stretch of real estate — I've never seen such massive stupidity. This is the only town where I've ever been refused entry into a bar — and it happened twice in one night."

On that same topic, Honerkamp adds that while he prefers not to mention specific names, the area's reliance on promoters — people who move from club to club generating of-the-moment publicity that has nothing to do with substance A makes him sick: "The posturing, the pure posturing that goes on is enormous. In any sophisticated city, it would be laughed at. I just thank God that in my worst desperation financially, I never reached as low as to hire one of these people who say, 'Pay me and I can make [your club] hip.' In that way, in my personal opinion, this place is just a sewer."

Arthur Barron believes that the Talkhouse's high overhead, and its proprietors' status as outsiders, resulted in an unfriendly tension that was tangible inside the walls of the club. "A nightclub is like a living, breathing organism, a home for its own subculture," he says. "The owners set the vibe. There was a reason people wouldn't hang out there after a show."

Perhaps not surprisingly, Barron is just as adamant in his empathy for the Talkhouse's owners: "They got beat up a lot of times. This is just a horror to a club owner. Not just the fact of losing money. You spent so much time in trying to do the right thing A all the days you spent constructing that place, the sleepless nights. You finish and you feel like you've got it made, and then no one shows up. You feel like fucking dying. It really takes the guts out of you."

"This isn't all that great a turnout for Nil Lara. That people just can't seem to get together and have a good time listening to music — I take it as a sign there's something really wrong in this country."

Like many fine conversations that take place in bars, this one moves rapidly from the specific to the general, and stays there. And like many such conversations, it begins in the vicinity of the men's room. Finally, this being the end of the evening, the speaker is nearly as well-lit as the neon on Ocean Drive.

On stage Nil Lara is wrapping things up, having played one more encore than he'd intended. Through the haze of stale air and smoke that has been rising since the show began, the Sound God in his distant booth looks like an apparition, his head crowned by a shaggy nimbus of thinning hair.

"There just doesn't seem to be that basic contract between human beings any more — the agreement that 'I won't hurt you,'" the man says. A regular Talkhouse fixture who favors bright Hawaiian shirts and a beat-up Panama hat, he is Michael Genth, one of the club's investors. Honerkamp and Gallo met him in Ibiza. He's in his sixties, with delicate features and the tolerant, reflective demeanor Americans tend to develop when they spend long periods of time out of the country.

In a more sober, though equally sobering, moment of reflection, Honerkamp says South Beach's lack of community might be at the root of his own disaffection. "People can grow up in good households even if the family breaks up, but people who come from stable families do better. In the same way, I think, transient towns suffer, whether they be Houston or Miami or L.A. I think you need a certain percentage of people who grew up together, who went to the same community centers, churches, whatever, and then to the same bars. Here, everyone is constantly coming and going, and I think it makes people more superficial and more on the scam."

Honerkamp doesn't want to go into details about the sale of the bar — "Something could always go wrong at the last minute," he says — and refers questions to Neisen Kasdin, the attorney for the prospective buyer (and a Miami Beach city commissioner). Citing his client's right to privacy, Kasdin declines to comment about the sale price or the buyer's plans.

Most Talkhouse staffers have been offered jobs for the season at the Long Island club. Some, such as bartender-investor Paul Coyne, will make the trip north for the summer and then return to Miami Beach. Drew Holshouser, a Coconut Grove native, will stay in South Florida. After a vacation, he'll likely look for freelance work.

Loren Gallo will stay here, too. He's hoping to promote shows on a part-time basis. "I look at this like we succeeded in doing something. When you see a lot of music, and there's so many memorable shows that come to mind, that's something to be proud of. It's just not permanent, unfortunately," he says.

"This was a great place to work," says Mia Johnson, the club's manager, over a 4:00 a.m. beer at the patio bar. After pausing to renew her acquaintance with a smoldering Marlboro Light, she says that she'll accept Honerkamp's offer for summer employment up north, then look for similar work in New York City after business dies down in September. "Bars like the Talkhouse are like a family," Johnson explains. "This kind of life — it gets in your blood." She picks up a shot glass filled to the brim with Cuervo Gold, and with one smooth swallow makes the figurative literal.