Aboard the sleek, new Shalom, the pride of the Israeli fleet, a bit of dancing and merriment was still going on at 2 a.m. when a strange grinding noise forced the band to interrupt its tune. The drummer clumsily fell off his stool.

It was a frigid and foggy Thanksgiving night in 1964, and the passenger liner, with 616 men, women, and children aboard, had set off three hours earlier on a cruise from New York through bad weather. It was headed to the island of Antigua in the Caribbean. Some of the late-night partiers were reassured by the crew. Everything was OK. So they did what most cruise ship passengers do on the first drinkup of a long voyage: continued partying. A handful of them thought the ship had struck a drifting log. Others shuffled from their cabins in nightgowns and asked if everything was all right. The crew stoically maintained all was indeed fine.

The Stolt Dagali, on the other hand, was not fine. The first SOS went out at 2:23 a.m. It wasn't until 30 minutes later that Capt. Kristian Bendiksen realized his entire stern had disappeared. The 582-foot Norwegian tanker had been literally cut in half. Instantly, the crew of the Stolt Dagali, which was laden with fats and oils headed for Newark, was thrown into chaos. Ten men, along with the captain, were able to remain aboard the still-buoyant front section of the ship. The rest of the 43 crew members were either thrown directly from their bunks into the freezing sea or jostled overboard. Eight men eventually were able to get into a lifeboat. All those who ended up in the Atlantic without warning were barely clothed and covered in oil, desperately splashing around, fearing for their lives. They could last maybe 30 minutes, an hour max, in the frigid waters.

"Maintain radio silence. You are in a Russian missile impact zone!"

tweet this

In stark contrast, some people on the Shalom assumed the rough ride was over and went back to sleep. After an announcement from Capt. Avner Freudenberg that all should awaken and don life jackets, a crowd in fur coats and pajamas eventually began to form on deck, some snapping pictures of the scene. The bars reopened, and the band played. There was a single injury aboard the Shalom: A stewardess named Marge Postalico was caught between a set of watertight hydraulic doors. Though her situation was dire, no one else aboard suffered even a scratch.

"The seas were rough, the fog was heavy, the Shalom sliced through like butter," Captain Bendiksen of the Stolt Dagali told the media once he and his surviving crew members were back on shore. The stern had sunk almost immediately. In the fog, the two ships had collided, and the turbulent weather and blustery wind made visual understanding of the situation nearly impossible.

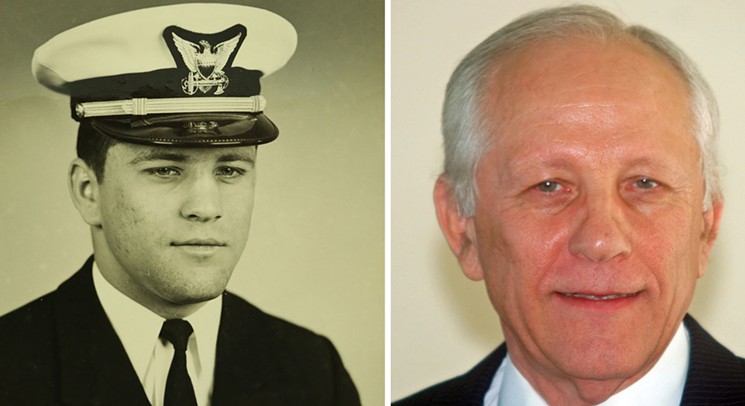

But the accident instantly put into motion one of the largest search-and-rescue operations of the time, combining 11 Coast Guard and Navy helicopters, six cutters, and even the crews of three passing Merchant Marine vessels acting as Good Samaritans. The operation was coordinated by Lt. Junior Grade Joseph DiBella, who was officer in charge at the Rescue Coordination Center in lower Manhattan. Functionally, the 24-year-old was fairly low-ranking for what was shaping up to be a massive effort. When his superior appeared and asked whether DiBella should be relieved, the message from top brass was: No, let him stay in control.

Fifty years later, sitting in his penthouse apartment overlooking Indian Creek in Miami Beach, 76-year-old Joe DiBella leans his wrestler's frame over a grayed box of archival material. Inside are the newspaper clippings and handwritten notes of the Shalom-Stolt Dagali incident. The brown, aged copies of the New York Times, New York Post, New York Herald Tribune, and other periodicals sit atop vintage photos of servicemen, his old friends, and superiors.

The box, along with those who lived through the crash, tells the story of the operation's inner workings. Though DiBella remains humble about his role, he is not shy about explaining how implausible the accident was, saying excitedly, "A ship was cut in half! You just don't see that. It's unbelievable! It's incredible!"

Adds Capt. James Durfee, then the U.S. Coast Guard's chief of search and rescue, who is now 94: "This was a big incident. No doubt about it. "

Joe DiBella was born in Rome, New York, a fact he'll happily tell most people once they've listened to his stories long enough. On the Ides of March in 1940, DiBella came into the world in that small, proud, bustling town. The oldest of nine siblings, he was born to an Italian father and Polish mother. His grandfather, Agatino DiBella, was a grocer and self-made man who came to America as an immigrant. DiBella's father, Cosimo, eventually took over a nightclub from his father-in-law, Stanley Dabrowski, a hotelier and Polish immigrant. Young Joe excelled at wrestling, which became his passion. He claims to be in three halls of fame for his prowess (Coast Guard Academy; Rome, New York; and New England) and almost made the U.S. Olympic team but was stymied by an injury to his ribs.

"It was the ticket," he says of wrestling. "It was the ticket that got me into the service academy."

But he had to decide where he would land in the military. "It was either killing people or saving people," he explains. Being a child of World War II and coming of age during the years of the Vietnam War, he didn't question whether to enter the service. So Joe DiBella left Rome when he was 18 to attend the United States Coast Guard Academy. He did his four years there and then spent four more in the Coast Guard.

"He and I stood a lot of watches together," says his Coast Guard brother and quartermaster, Bill Dickerson. "I've always called him 'Mr. DiBella,'?" a now-75-year-old Dickerson explains. He says DiBella was a "good-looking guy, looked great in a uniform, and he was just an all-American person besides being an all-American wrestler. "

DiBella would eventually prove to be a hero during his time in the Coast Guard. But it was not without some bumps along the way. As a young man in the service, he was not always on the right side of his higherups, or even other nation-states.

The first time DiBella was accused of spying was aboard the USCGC Blackhaw in May 1963. DiBella was operations officer of a small ship threading through the majestic atolls of the Pacific 1,700 miles southwest of Honolulu. They were leaving Howland Island, a deserted spot of coral that was home to Earhart Light, a day beacon named for the doomed aviatrix. The Blackhaw had been sent to repair the unlighted navigational landmark that had been damaged by the Japanese in World War II.

One evening, on the journey back from Howland to Honolulu, DiBella noticed a strange flash above him. "During the night when I was on watch, I saw something going through the sky like shooting stars, but they weren't white; they were yellow." As officer of the deck, he told the captain, but didn't think much of the incident. During his watch the next morning, three blips mysteriously appeared on the radar. Before they knew it, a trio of vessels was approaching but wouldn't communicate. Two smaller vessels broke off from formation, and a third came right at them. Over an air horn, a voice boomingly demanded, "Maintain radio silence. You are in a Russian missile impact zone!"

"There was a notice to mariners that we did not receive," DiBella explains about how they had strayed into the area.

Sure enough, right after the incident, a commander of a Soviet ship that had been in the impact area made a statement in the Honolulu Advertiser. He declared the men of the Blackhaw had "remained in the area on a spying mission." It was then that the American lieutenant realized the strange lights he had seen in the sky were missiles.

Of the espionage accusation, DiBella says, "It was absurd. It was laughable, because the Navy itself was monitoring the entire exercise, and the Russians knew it."

The second time DiBella was accused of espionage, it nearly cost him his life. Two years after the missile-test morass, he rode the famous Orient Express from Istanbul through Eastern Europe with Lt. Junior Grade Larry Dallaire, who had been quarterback of the Coast Guard football team under the tutelage of famed coach Otto Graham. Dallaire was DiBella's best friend in 1965 when the two took a month of shore leave for a trip around the world.

They flew from Delaware to France on an Air Force plane and then hopped onto other U.S. service planes to Tripoli, Athens, and Thessaloniki. After landing in Constantinople, they bought tickets for the Orient Express and traveled by train, eventually ending up on the Direct Line, which for a while during the Cold War went through Germany. Once in West Berlin, DiBella recalls, Dallaire suggested they go see the Wall. So in full uniform, they traveled by subway to East Berlin.

They didn't pass through the famous Checkpoint Charlie, an unassuming wooden shack surrounded by barricades and serious men with rifles that was one of the most heavily guarded access points for decades after World War II. It was also the only place Allied diplomats, military personnel, and foreign tourists were supposed to pass through to reach East Berlin.

"Everybody in the Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force knew that the only way you could go into Berlin was through Checkpoint Charlie," DiBella says. "But we were Coast Guard."

After snapping a few photos in East Berlin, which DiBella still has, they decided to return to the West. But they were quickly detained by authorities.

In East Berlin, the experience was relatively tame. DiBella and Dallaire convinced the guards they were Coast Guard and were sent on their way.

The Allied forces were not as friendly. "We have no log of you going in," an intimidating uniformed soldier said. Instantly, the two were placed under armed guard and in separate cars. It was the second time that day they were detained, and this one was much more intimidating.

In the dark and plain cellar beneath Checkpoint Charlie, DiBella was put in a chair in a sparse room. An interrogator asked him a series of questions meant to catch him in a lie about his alleged American citizenship.

"Who plays first base for the Yankees?" the man asked.

"Joe Pepitone."

"Where are you from?"

"Rome, New York," DiBella replied.

The interrogators then shuffled in a lumbering American serviceman, claiming he was from the same scrappy city of 50,000, 20 miles from Utica.

"He didn't know where Dandee Donuts was," DiBella says today through a smile. "He wasn't from Rome, New York."

Eventually, DiBella and Dallaire were placed on a four-hour sealed train to Bremerhaven. They were told they needed to leave the country immediately.

Was DiBella a spy? "Honest to God, no. If Larry and I didn't have on our Coast Guard uniforms, we would have never gotten back to the States."

Above the massive Corinthian columns of the Alexander Hamilton Custom House — an early-20th-century neoclassical building on the southern tip of Manhattan — was a quiet, business-like room filled with floor-to-ceiling nautical charts and the various implements of maritime tracking and communication. The rows of telephones were quiet because most of the Coast Guard staff was out for Thanksgiving. Lt. Junior Grade Joe DiBella was the officer on duty at the Rescue Coordination Center that evening in 1964. He, assistant controller/quartermaster Bill Dickerson, and a radio engineer were calmly standing by when the first frantic emergency signal came in.

"All of a sudden, the bells and whistles literally went off," Dickerson recalls, "and we just went into action."

The first call was an SOS from the Stolt Dagali at 2:23 a.m. DiBella ran through a series of questions. He needed to confirm distress, position, and the people onboard.

Two minutes later, the Shalom came in on another frequency. DiBella put the entire search-and-rescue apparatus in motion, rousing the pilots from their bunks and sending them to survey the scene.

But then DiBella realized something wasn't quite right with the positioning that came in with the SOS signals. After mapping the coordinates of their initial radio calls, DiBella figured out they were 15 miles apart, a detail that caused much initial confusion at the Rescue Center.

"I knew there was something out there serious," he recalls. Eventually, he got word from the first on-scene helicopter pilot. "Send everything, everything you got," he said.

DiBella called Navy backup in Lakehurst, almost 40 miles from the crash site, as well as the Coast Guard office at Floyd Bennett Field in Rockaway, on the southern tip of Long Island. Helicopters, along with a C-130 Hercules transport, were deployed.

"It was very exciting," Dickerson recalls. "I was like, 'Oh my God, ya know something is really going on.'?" The rescue operation went on for hours.

"My whole stern has disappeared," Captain Bendiksen radioed at 2:52 a.m. It took a turbulent half-hour to realize his ship had been cut in half and 140 feet of it had sunk.

At 3:50 a.m., the Shalom radioed for help. Marge Postalico, the stewardess who had been caught between hydraulic doors, was suffering internal bleeding. DiBella was faced with a conundrum: How to balance the people already in a dire situation in the water and a possibly less serious case? He called for another helicopter from Floyd Bennett. That call saved Postalico's life.

Soon, Coast Guard Rear Admiral Irvin Stephens arrived. A decorated war hero from both WWII and Korea, Stephens had just moved north from his command of the Coast Guard Seventh District in Miami, where he had received high praise for his handling of USCG operations during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Chief of the search-and-rescue branch and DiBella's superior, Captain Durfee, asked the admiral whether he — as senior officer — wanted to take over the operation. The admiral's reply: "Nope." Leaving a lieutenant junior grade in charge of such a large operation was a risk, but it showed faith. "That made me feel good," DiBella says.

"He got word from the first on-scene helicopter pilot: "Send everything, everything you got."

tweet this

Durfee thinks he was probably asleep at the time of the late-night collision. "DiBella was definitely the point man. He was onsite; he was right there at the desk... And he was the first one to take action on it. He called in the necessary people; he alerted the radio stations; he alerted the operational commands, the ships, and aircraft stations."

Visibility was quite limited for the 11 helicopters that hovered over the surreal sight of half a ship in the Atlantic Ocean.

"It was a shock," Navy copilot Leif Elstad, now 77, says of seeing the Stolt Dagali sliced in two. Elstad spent around an hour and a half in the air in deep fog and 25 mph winds. He and his crew flew to the site in a Kaman UH-2A aircraft that airmen of the day had nicknamed "Hookie Tookie" for its previous call letters (HU2K-1). The craft was ideal for harsh conditions.

Elstad recalls his crew lowered a cable with a horse-collar rescue strop, a U-shaped device on a winch used to raise survivors to the helicopter. "We picked up one fellow and lowered the hoist to pick up another one, and while that was transpiring, I looked over my shoulder and was very surprised to see that the person we had picked up was not a fellow; it was a female," Elstad says. That was the only woman on the Stolt Dagali, a stewardess named Berglijot Haukvig, whose husband was also aboard. (He was never found.) Then Elstad and his crew snagged their rescue cable on a mast and antennae rigged on the Stolt Dagali. They couldn't free it, so they cut loose and returned to the Navy yard at Lakehurst.

Thirty-three men were flushed off the Stolt Dagali and into the water from the sinking stern, while ten remained on the mangled bow, which stayed afloat. The Shalom put a boat in the water that rescued five men from the waves. One more made it to a merchant ship that had arrived to help, and eight reached a lifeboat. All of the survivors were picked up by the assisting helicopters and airlifted to the Naval base at Lakehurst. Twelve bodies were recovered, and seven crewmen of the Stolt Dagali never came out of the Atlantic.

"The sky was busy," Elstad says. "There were a lot of helicopters involved." In the end, 24 people were pulled from the water or the floating bow of the Stolt Dagali. Some were near death. One victim, Aadvar Olsen, was tugged from the water into a rescue boat and then up to a helicopter in a rescue basket. He was still in his underwear when they brought him aboard the aircraft; his hand clung to the basket so tightly that it took multiple men to pry it loose. All of the survivors were hospitalized.

The search for remaining survivors was called off at 11:57 a.m. It had been almost ten hours, and any chance of the remaining sailors being found alive was gone.

Bjørn Arne Kleppe was another helicopter pilot on the mission. He was a Norwegian citizen who enlisted in the United States Navy for a few years through a NATO program. Today, Kleppe recalls visiting his countrymen in the infirmary at Lakehurst. None of them knew what Thanksgiving was, but he says they were grateful for the turkey they ate in solemn silence. "I spent many hours in the sick bay talking to the survivors, trying to comfort those in shock," he explains. "I think many of the survivors needed someone who would listen and talk in their native language."

Many were in deep shock. Even after being on shore and in a hospital, some thought they were still in the water fighting for their lives.

"At the time," Dickerson says, "that was probably the largest and to me the most dramatic coordination we had... The adrenaline really builds up. I mean, it really does."

DiBella, for his part, was all business: "There's no time in the Rescue Center to start, 'Uh, well what are we gonna do? How should we do this?' Boom. I enjoyed it."

Dickerson remembers the relief of it all being over. "An hour or so, maybe two hours later... the units were on scene doing their things, the rescues and the vessels were en route, and I remember just looking at Joe and he looked at me. And I said, 'Geez, I mean, you know, I mean, wow, that's it, what else can we do?' We had done everything. And I remember really feeling good about that, and I know he did too."

After the accident, when the Shalom was dragged into port, Capt. Jack Goldthorpe remembers seeing a 40-foot gash in its side. It was "at the bow, at the waterline... You gotta realize the Stolt Dagali was a loaded tanker, so it's going to be kind of low in the water. When the Shalom hit it and sliced it in two, it was maybe 30 to 40 feet." Goldthorpe was the Coast Guard's public relations officer at the time, so most of his energy went into answering phone calls from concerned relatives and newspaper reporters. Once the press got hold of the story, all hell broke loose. "The phones were ringing off the hook," Goldthorpe remembers.

The lead story in the New York Herald Tribune on November 27, 1964, was headlined "Disaster and Courage at Sea." It showed two large photos: one of the gruesome laceration in the Shalom's hull and another of the dismembered bow of the Stolt Dagali.

The collision was front-page news across the United States. The newspapermen held nothing back in the detailed accounts of the tragedy and rescue operation.

Eventually, the Shalom was rebuilt and put back to sea. Even the bow of the Stolt Dagali was rebuilt in combination with another wrecked ship and rechristened the Stolt Lady. The legal battle among Zim, owner of the Shalom; A/S Ocean, owner of the Stolt Dagali; and Pacific Oil Corp., whose cargo of oils and fats spilled into the Atlantic, continued for years. In December 1964, A/S Ocean seized the Nahariya, another Zim ship, in Sweden. The Israeli company sued for $2.3 million. In the end, the matter was settled out of court.

What caused the crash? Fog was a factor, but both ships' crews also made mistakes that caused the collision that took 19 lives. The Shalom was going too fast and should have slowed down in the poor visibility; its secondary radar system was inoperable, which might have caused the initial 15-mile misread between the two ships, as well as the crash itself.

"If anybody wants to know something about history, I'm the first person they contact."

tweet this

The crew of the Stolt Dagali had seen the other ship on radar with enough time to avert the collision but didn't make the necessary maneuvers, waiting erroneously for the other ship to perform evasive action and pass astern.

Today the only remnant of the accident lies 130 feet at the bottom of the Atlantic. The stern of the Stolt Dagali sits 23 nautical miles offshore and is one of the most popular attractions for scuba divers off the New Jersey coast. It's covered in algae, mussels, and other sea life.

"It's one of the more spectacular shipwrecks that happened off our coast," says David Swope, researcher for the New Jersey Maritime Museum. "I've been on it several times. It's very picturesque." Swope's museum displays the second anchor of the Stolt Dagali on its front lawn, as well as some life preservers and a fully interpreted display about the wreck.

However, perhaps the most interesting memory is that of Joe DiBella, who remains modest about his role in the rescue and the lives saved. "My life wasn't in danger," he says. "I wasn't flying a helicopter in the dark and hoping there was enough illumination coming from the C-130."

But of all the people involved in the operation, DiBella was the only one personally recognized for his involvement. In April 1965, he received a letter of commendation from the commandant of the Coast Guard. He still has a faded black-and-white photo that shows a rakishly handsome young officer receiving the certificate from the bald and distinguished admiral. A picture of the severed bow of the Stolt Dagali hangs between them.

"I accepted it, but I didn't accept being some kind of hero," DiBella says. "I hate that. I accepted it; I had to... What I did was routine. Anybody could have done it."

When speaking of the search-and-rescue staff, DiBella laughs. "These pilots, they're funny. They said, 'There's Joe up there drinking hot coffee, and we're out there risking our lives, and he's the one who gets the medal.'?" And he really does see it that way — that he didn't deserve the praise. He gave a signed photocopy of his commendation to his good friend Dickerson, who remembers the inscription fondly: "To my cohort Bill Dickerson, I couldn't have done it without you. Best, Joe."

Despite DiBella's modesty, the commendation letter remains the official truth: "[By his] meritorious service, [he] upheld the highest traditions of the United States Coast Guard."

DiBella left the Coast Guard in 1966 to attend Columbia Business School and run his own business, as his father and grandfather had done before him. Also, he says, "I believe quite a bit in family." At Columbia, he met and married his wife, Françoise, a French citizen. They moved to Miami after he took a job with Eastern Airlines because of his fascination with aviation. They have two daughters, Alexandra and Melissa, whom he has photographed (or demands a photo be sent) every month of their lives since birth. His love of family is apparent when he speaks of his four grandchildren and their regular visits. He is now the patriarch; both of his daughters and his eight siblings look to him for guidance.

After his brief stint in aviation, DiBella went on to work for decades in the insurance industry as the president of the General Insurance Company. He left that post in the mid-'90s and has consulted ever since. He swims in the Atlantic, across the street from his home, every Sunday. Family now is everything. Tears well up in his eyes when he thinks of his grandchildren.

He describes his Coast Guard adventures at a massive dinner table in a large, mostly white penthouse. Floor-to-ceiling file boxes, remnants of his life's work, once filled the apartment. But DiBella has scanned most of them. The box that holds the Shalom-Stolt Dagali incident materials is one of the last left.

"I'm known as the archivist in our class," DiBella laughs at his reputation among his Coast Guard mates. "If anybody wants to know something about history, I'm the first person they contact."

DiBella proudly holds a book containing a published letter from his wife's grandfather. He clutches the book lovingly and speaks with great reverence. The letter in the tome was found on her grandfather's body, written the night before he was killed in action by the Germans in Vermelles in 1914. In it, he recognizes his fate, says a loving and fateful goodbye, and mentions a baby, who was Françoise's father. Though generally talkative, DiBella remains oddly silent when holding this book. Family, service, and looming mortality.

DiBella says he left the military and never looked back. He had saved lives in the Shalom-Stolt Dagali incident that Thanksgiving Day in 1964 and served his country. Today, reviewing the newspapers and artifacts of the operation, DiBella says quite honestly of his years in the Coast Guard: "I didn't kill anybody." And, thankfully, he says, "I sleep."