The call came from California. A woman told Coral Springs Police she had recently learned something terrible: A South Florida man had molested her daughter for years. It began when the girl was just 4 years old.

An officer noted the information and called the victim, who was then a teenager. She confirmed the story in stomach-churning detail.

The man had forced her to perform oral sex, she said. He would regularly "finger and fondle her" genitals, make her touch his penis, and "dirty talk" to her. The abuse lasted until she was a teenager, she told the cop. She'd never even told her family about the crimes.

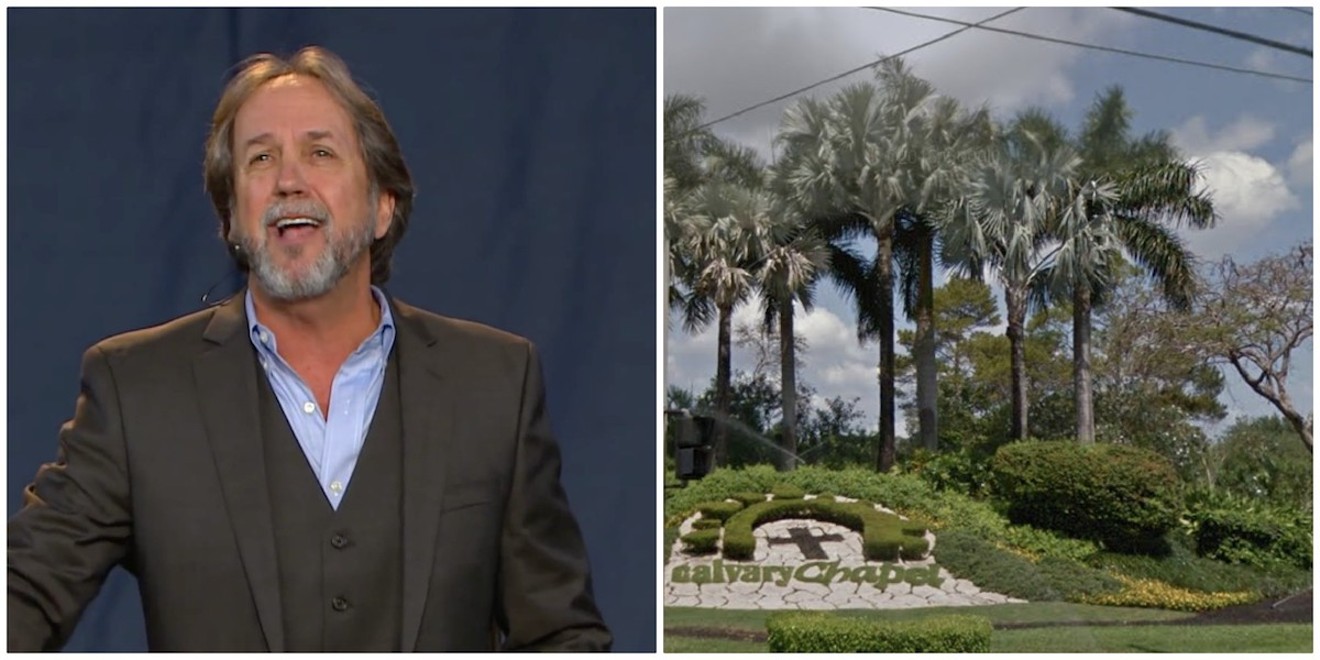

By the end of that harrowing call on August 20, 2015, police knew the accused predator was no ordinary suspect. His name was Bob Coy, and until the previous year, he'd been the most famous Evangelical pastor in Florida.

Over two decades, Coy had built a small storefront church into Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, a 25,000-member powerhouse that packed Dolphin Stadium for Easter services while Coy hosted everyone from George W. Bush to Benjamin Netanyahu. With a sitcom dad's wholesome looks, a standup comedian's snappy timing, and an unlikely redemption tale of ditching a career managing Vegas strip clubs to find Jesus, Coy had become a Christian TV and radio superstar.

But then, in April 2014, he resigned in disgrace after admitting to multiple affairs and a pornography addiction. Coy shocked his flock and made national headlines by walking away from his ministry, selling his house, and divorcing his wife.

The sexual assault claims, which have never before been divulged, raise new questions about the pastor, his church, and the police who handled the case. Documents show that Coral Springs cops sat on the accusations for months before dropping the inquiry without even interviewing Coy. His attorneys, meanwhile, persuaded a judge with deep Republican ties to seal the ex-pastor's divorce file to protect Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale from scrutiny.

The revelations come at a sensitive moment for Calvary's national network of about 1,800 churches, which have been riven by legal infighting and dogged by claims that bad pastors have been allowed to run amok. In fact, at least eight pastors, staffers, and volunteers in Calvary Chapel's network around the United States have been charged with abusing children since 2010. In one case, victims claimed the church knowingly moved a pedophile to another city without warning parents.

"Religious leaders have a tremendous amount of power over their flock," says Scott Thumma, a professor of sociology of religion at Hartford Seminary who has studied the Calvary movement. "If Calvary gives these pastors this much authority and they use and abuse it with no accountability, they have to blame themselves."

Coy, who was never charged with a crime, lay low after leaving Calvary but recently turned up at Boca Raton's Funky Biscuit, where he helps manage the club. (Update: The club has now terminated its relationship with Coy and says it had no inkling of the allegations against him.) Tracked down at the bar on a recent weeknight, the well-dressed ex-pastor looks no different from the days when he preached to thousands of followers. He declined to discuss the child abuse case except to say he is innocent and passed a polygraph test to prove it.

"I can't discuss it on the record," he said, before adding cryptically: "If you're foolish enough to go through with this story... it would hurt a lot of people."

Were there other abuse claims against Coy during the nearly three decades he controlled Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale? The church won't say, though a spokesman says the chapel was "saddened to hear of the allegations." That's not good enough, critics say.

"There could be other victims out there," says Michael Newnham, an Oregon-based pastor who runs a blog critical of Calvary Chapel. "We need answers."

Coy's life story is biblical in scope and obvious in moral lessons. Long before his epic fall from grace, the pastor used his own struggles with sex and drugs to preach that anyone could find redemption in Jesus.

Born in 1955 and raised in Royal Oak, a suburb north of Detroit, he grew up in a strict Lutheran family but didn't buy into the church. "I was brought up in a very religious, traditional Midwestern home," he told Ed Stetzer, a Wheaton College professor, in a 2013 interview for a video series. "I was brought into the Lutheran church without a choice... that's where I learned what a religious environment was like, but I was missing the spiritual thing."

Instead, Coy drifted to his hometown's specialty: rock music. In his 1973 senior class portrait, his dark hair, parted neatly down the middle, hangs well past his shoulders. After graduating, he found a career in the entertainment industry. In fact, he says Capitol Records paid him to party.

"I was living a life of sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll, literally," Coy told Stetzer. "My job was to make sure that the artists on Capitol Records were happy and entertained when they were in my city. That lent itself to a very youthful, crazy, wild lifestyle. So crazy that I became addicted to cocaine."

Even in the chemically altered '70s music business, Coy's appetites were too voracious. So after some unspecified "very embarrassing behavior," Capitol fired him. Coy then moved to an even more debauched scene: Las Vegas. He found work as the entertainment director at the Jolly Trolley, a storefront casino and strip club, where he said he wasted away his early 20s in a haze of sex, coke, and alcohol.

But in 1981, his life changed forever thanks to an epic holiday hangover and his brother Jim, who'd already found religion.

"I had been invited to his house for Christmas dinner and I skipped it," Coy told Stetzer. "We had a big party at the casino — girls, cocaine, alcohol, the whole thing. I was feeling horrible."

He quit the cocaine and strippers, met his wife, and moved to South Florida to preach.

tweet this

When a blitzed, 26-year-old Coy went to see his brother the next day, Jim threw a Bible at him and told him to read it. Coy opened it to the Gospel of John, and by the time he hit 3:16 — "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life" — he said he was weeping uncontrollably.

He was ready to give his life to the church.

He quit the cocaine and strippers, began training as a preacher, met his wife Diane, and moved to South Florida. Coy rented space for his church from a funeral parlor in Oakland Park and made ends meet by selling shoes while his wife worked as a waitress.

Coy aligned his fledgling church with Calvary Chapel, a movement started in Southern California in the 1960s by Chuck Smith, a laid-back West Coaster who wore Hawaiian shirts while he preached a fire-and-brimstone, old-school religion. Smith was among the first pastors to make a startling discovery: Many of the hippies and disaffected youth who'd come for the Summer of Love had realized psychedelic drugs and the Grateful Dead weren't filling the holes in their lives. They wanted spirituality but could never go back to their parents' churches.

At Smith's church, "you could come in jeans, and it didn't matter what your hair looked like or how long your beard was," says Thumma, the Hartford professor. "It was attractive on both sides, for the Christians who hadn't really gotten into the drug culture but were younger and wanted something new... and for the people who had come through '60s free love and drugs and needed some stability."

Smith even launched a music label and began fusing Evangelical faith with electric guitars and drum kits. His idea was a huge hit, one of the first in a wave that has become known as the Jesus movement. His church started with just 25 members in a Costa Mesa lot in 1965, but by the mid-2000s, it had grown to include hundreds of affiliated chapels around the nation and internationally plus a lucrative array of radio stations.

With his tale of drug addiction and strip clubs, the newly redeemed Coy was a perfect fit for Calvary's edgier message. And Coy turned out to be a charismatic preacher. He's an engaging storyteller — "somewhere between Billy Graham and Billy Crystal," the Miami Herald once suggested — with an easy laugh and a voice that excitedly rises into high nasal registers.

By 1986, his church had outgrown the funeral parlor and attracted about 1,200 regulars to an Oakland Park chapel. He had a staff of 13. Like his mentor Smith, he looked for converts in unusual places. As spring breakers poured into Fort Lauderdale to bong beers, he set up "The Recovery Room" at the Jolly Roger motel, where he offered live music, first aid, and — of course — Evangelical literature. Coy soon upgraded again, by moving to a warehouse in Pompano Beach, where thousands came every week to watch him preach.

"We loved him because of his realness. He never hid who he was," says Tina Rivera-John, who began attending Calvary in the mid-'90s when she was 12 years old. "He was just transparent, and he could be very funny as well."

Like Smith, though, Coy used his relaxed persona to sell a deeply conservative brand of Christianity. He ran gay-conversion groups and preached that all nonbelievers would go to Hell. As his star rose and his congregation grew into the tens of thousands, the Sun Sentinel solicited weekly faith columns written by Coy. In a piece about the Iraq War, he called Saddam Hussein a "rabid dog" and wrote that "we cannot simply sit idly by and let evil happen." In another, he called adultery "the ultimate betrayal of trust in human relationship" and cautioned that "repentance is not just being sorry that you were caught."

In 1996, the church paid $21 million for a 75-acre campus just east of Florida's Turnpike off Cyprus Creek Road, where Coy often dipped into politics to guide his massive flock. His church fought in 2002 to remove LGBT people from protection under Broward's Human Rights Ordinance, and Coy loudly defended George W. Bush's disastrous Iraq War: "I believe in war because it's biblical, scriptural, and religious," he told his followers in one sermon. In 2004, he even campaigned with Dubya around South Florida.

Coy sued Fort Lauderdale in 2003 after the city tried to block Calvary from placing a sign with a Christian message at a Christmas light show. Coy's church won the suit — plus $81,000 in damages and fees — and the city, which organized the event, stopped offering sponsorships out of concern that hate groups might take advantage of the ruling.

Coy became a key endorsement for local Republicans, including conspiracy theorist U.S. Rep. Allen West, whom Calvary hosted as a keynote speaker at a conference to train more than 100 local conservatives to run for office more effectively.

Calvary was among the first churches in the nation to air podcasts, stream services online, and simulcast sermons at satellite campuses (the church had opened campuses in Plantation and Boca). His popularity soared. He toured the nation on Evangelical radio and TV shows, hung around with Billy Graham, and published books and CDs.

In 2005, Coy's church rented out Dolphin Stadium on Easter Sunday and drew more than 20,000 people. The next year, he raised an insane $103 million in donations — the most by a single megachurch to date. He sat on a U.S. presidential advisory board and received weekly updates straight from GOP mastermind Karl Rove. In 2006, gubernatorial candidates Charlie Crist and Tom Gallagher personally pleaded for Coy's endorsement, though he declined.

Coy had forsaken rock 'n' roll for Jesus but then became a rock star anyway. Huge crowds hung on his every word. Young women begged for photos. And somewhere along the line, Coy slipped right back into his old life.

On a Sunday evening in April 2014, thousands packed into Calvary Chapel's sanctuary, a cavernous space that looks more like a midsize city's convention center than a church. As they sank into plush, arena-style seats and flipped open well-thumbed copies of the Bible, Coy's followers quickly noticed something was very wrong. The rock band that usually played raucous hymns to start services was missing. And a grim-looking assistant pastor, gripping a letter, was walking across the stage.

Pastor Bob had suddenly resigned, the assistant pastor told the stunned crowd. He had admitted to a grave "moral failing." Ushers passed tissue boxes down the rows as his followers wept.

"People were really, really hurt," says Colleen Healy, a Broward resident who began following Coy in 1995. "I was really hurt. I'll never forget that meeting."

Coy's preaching career ended with shocking speed, but his sex scandal was far from the first for Calvary Chapel. In fact, the church had been battling accusations nationwide for years that it empowered predatory pastors while demanding little accountability.

The root of Calvary's problems, critics say, lies in its unique structure. Unlike many Protestant churches, which set up powerful boards of elders to oversee ministers, Calvary used a management style Smith called the "Moses method."

"Moses was the leader appointed by God," Smith told Christianity Today in 2007. "We are not led by a board of elders."

Instead, the pastors Smith installed in his hundreds of megachurches, which are similar to Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, had nearly unlimited power over budgets, personnel, and message. And even if complaints arose, Smith's answer was often to give wayward preachers second and third chances.

In 2007, Christianity Today spoke to numerous Calvary pastors across the country. Some complained anonymously that Smith was "dangerously lax in maintaining standards for sexual morality" among his preachers. "Those men cannot call sin sin," one 20-year veteran of the church complained to the publication.

Coy's preaching career ended, but his sex scandal was far from the first for Calvary.

tweet this

There were ample cases to make that point. In 2003, John Flores, a pastor at Smith's flagship in Costa Mesa, was arrested for having sex with the 15-year-old daughter of another pastor. According to Christianity Today, he'd been fired twice before for sexual misconduct, including once after getting caught having sex on church grounds, but kept getting his job back. (Flores was eventually convicted of sex with the minor.)

Two years later, a Calvary Chapel in Laguna Beach fired its pastor for adultery and embezzlement — but Smith quickly rehired him to preach at the nearby Costa Mesa church.

That same year, the church found itself in a bizarre scandal centered on a lucrative, 400-station radio network and its head, Idaho-based Pastor Mike Kestler. He had been in hot water in the '90s when multiple women in his church claimed he'd sexually harassed them, but Smith gave him another chance.

In a lawsuit, a woman named Lori Pollitt said after she had moved from Texas to Idaho to work for Kestler, he repeatedly demanded she divorce her husband, give up her children to adoption, and marry him. When she rebuffed him, she said he stalked her and put a "hangman's noose" in front of her house.

This time, Smith and his son Jeff actually turned on their pastor, pushing him out. They ended up locked in dueling lawsuits, with the pastor accusing Calvary's leaders of skimming profits and the Smiths charging that he used his influence running the radio stations to pressure women into sex. (The cases were settled out of court.)

The next year, Santa Ana police investigated the Costa Mesa chapel after a 12-year-old told a staffer that a pastor had been touching her inappropriately. Police said they couldn't find enough evidence to press charges, but the staffer claimed the church forced him to resign for alerting the authorities.

In 2006, Coy's church in Fort Lauderdale landed in court over claims of lax oversight. A Calvary Chapel member named Rodger Thomas was arrested that year and charged with repeatedly molesting a 15-year-old girl at a high school run by the church. Two years later, her family sued Calvary, alleging leaders should have done more to stop Thomas. A jury awarded the family $360,000 but ruled Calvary wasn't culpable.

The most serious claim against Calvary's national church came in 2011, when four men in Idaho filed a federal suit alleging a youth minister named Anthony Iglesias had molested them between 2000 and 2003. Even worse, they said church officials knew full well he was a pedophile: He'd been kicked out of another Calvary youth ministry in California after being charged with sex crimes there.

That case was settled out of court, but the attorney who brought the case says that, in general terms, Smith's habit of forgiving and rehiring pastors who have committed sexual offenses is a recipe for disaster.

"Typically, how it goes in these cases is you have a violator in the church, but the leaders will have this notion that if he repents, he's forgiven, and then we don't have to talk about it any more," says Leander James, who specializes in church child abuse cases. "That whole approach always ends up hiding pedophiles."

Neither Calvary Chapel Costa Mesa, the movement's flagship, nor the Calvary Chapel Association returned messages from New Times seeking comment for this story.

It's still not clear how Coy's sexual indiscretions came to light in 2014. But two weeks after his surprise resignation, Assistant Pastor Chet Lowe filled Coy's followers in on what had happened.

"Our former pastor was caught in sin," Lowe said April 16, according to the Sun Sentinel. "Our pastor, he committed adultery with more than one woman. Our pastor, he committed sexual immorality, habitually, through pornography. Rest assured, God will not be mocked."

Coy's flock, which had followed him for decades as the church became Florida's largest, was devastated. Hundreds left or found other churches while Calvary scrambled to find a new leader, eventually settling on Pastor Doug Sauder, a less flashy but respected veteran of the organization.

"When Pastor Bob left, people definitely left too because they wanted to follow him or because they were just hurt," says Healy, the longtime church member.

Coy's faithful didn't know it, but just over a year after the pastor's resignation for adultery, Coral Springs Police launched their investigation into a far worse allegation. It's unclear how seriously they took the claim of the teenager — whom New Times is not naming in accordance with our policy on reporting on victims of sexual abuse — who said Coy had forced her to have sex even when she was only 4 years old. But the case soon stalled.

The department assigned the case to Det. Jeff Payne, a veteran investigator in the usually sleepy, affluent suburb of 120,000. Payne had experience with sensitive cases involving sex crimes; earlier that year, he'd investigated a high-ranking cop for allegedly assaulting a 13-year-old girl. Payne had taken his case against Fort Lauderdale Police Maj. Eric Brogna to the Broward County State Attorney's Office, but prosecutors declined to press charges.

In the Coy case, though, Payne never made that kind of headway. Shortly after resigning, the disgraced pastor moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Calvary Chapel has another affiliate church. (It's unclear if he worked there.) Coy says he was never approached by the police about the allegations.

Indeed, police records show no progress on the case until eight months later, on April 4, 2016, when Coy's young accuser showed up at Coral Springs Police headquarters. She told Payne she was "moving tomorrow [overseas] on a mission trip with the church, and asked if it was possible to destroy any record of [her] abuse," the detective wrote in a closeout memo. The woman told him "she had an experience with God and has found forgiveness" for Coy over his abuse.

The detective told her that he couldn't destroy the files, but he closed the case that day. Coy wouldn't be charged over her allegations. Broward State Attorney Mike Satz says he was never notified about the investigation.

"The law enforcement agency makes [its] decision on whether to bring the case to us," says Ron Ishoy, a spokesman for Satz. "They do what they feel is right based on the evidence they have."

It's October 2017, and Bob Coy hunches over a laptop in a far corner of the Funky Biscuit, a dimly lit club in Mizner Park in Boca Raton. The New Jersey-based folk-rock band Driftwood is still a few hours from taking the stage, and a handful of early arrivals sip beer and laugh over the canned blues soundtrack.

Although he's spent years away from the altar, Coy still looks straight out of central casting for a hip Evangelical preacher. His gray goatee is neatly trimmed, and he wears a light-blue plaid shirt and expensive jeans. But since returning to South Florida, he's spent most nights here, helping run the Funky Biscuit — a late return to his music industry roots.

Coy is friendly and voluble, but his lively green eyes suddenly brim with tears when he's asked about the sexual assault claims.

"If we go off the record, I could tell you a lot," he says. "I took a polygraph." But he declines to share the results of the test, which he says was not done for the police. He claims his record as pastor at Calvary Chapel was unblemished by sexual harassment or molestation claims.

"There were no other allegations," he says. "Never."

Coy has never been criminally charged, and if there were other cases of sexual harassment or abuse in the decades he ran Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale, neither the church nor cops have revealed them. The church didn't respond to a detailed set of questions from New Times, instead sending a general statement about the former pastor.

"We learned of this report after it was disclosed and reported to the appropriate authorities," says Michael Miller, a church spokesman. "We take every allegation of abuse seriously, and our prayers are with the Coy family as they pursue redemption and healing."

"She had an experience with God and has found forgiveness" for Coy over his abuse.

tweet this

The church Coy helped build has moved on without him, but the national Calvary organization has struggled. In late 2013, Chuck Smith died at the age of 86 after battling lung cancer. His daughter, Janette Manderson, and his widow, Kay, sued the organization, alleging its leaders conspired to take over Smith's empire and even denied him emergency medical care on his deathbed. Their lawsuit was dismissed this past July. (Attorneys for both sides declined to comment on the terms.)

Amid that legal battle, the movement essentially split in half shortly after Smith's death. The founder's son-in-law, Brian Brodersen, left the network of Calvary churches and started his own organization with many of the chapels, including Coy's old church in Fort Lauderdale. Others stayed in Smith's original system.

"When Chuck Smith died, there was nothing left to hold back all the competing factions," church critic Michael Newnham says. "They have been at war ever since."

This year, Calvary has been hit by even more sexual abuse claims. In May, Matt Tague, an assistant pastor at North Coast Calvary Chapel in San Diego, was arrested on 16 counts of lewd and lascivious acts on a minor under 14 years old. Police say the victim wasn't a church member, and Calvary Chapel says it immediately fired Tague upon learning about the claims.

Then, on July 18, police arrested 41-year-old Roshad Thomas, who had spent 13 years as a volunteer youth pastor at Calvary Chapel Tallahassee. He's accused of molesting at least ten children aged 13 to 16 over several years, victimizing members of the youth group he led after taking them back to his apartment.

Police say Thomas has admitted to the abuse (though his criminal trial is pending). The chapel's founder, Kent Nottingham, told a local TV station that there'd been no suspicion of abuse and that he was "shocked."

Coy has also been dragged through legal battlefields since his resignation from the church. In January 2016, he and Diane filed for divorce in Broward County. They'd already sold their Coral Springs house about six months after he resigned; the settlement divided their substantial remaining assets — including a $330,000 Hillsboro Beach condo he still owns — and defined custody of their two children. The divorce file includes nearly 30 pages of documents related to their finances and settlements.

But on February 22 of that year, the case went to Judge Tim Bailey, a member of a powerful conservative family; his father, Patrick, founded the Pompano Beach Republican Club, and both father and son had chaired Broward's Judicial Nominating Commission. That body recommends candidates for higher legal office to the governor. In Coy's case, Bailey made a relatively unusual ruling: All financial documents would be kept secret. Why? To "avoid substantial injury" to Coy's former employer — Calvary Chapel — according to the court file.

To critics such as Newnham, there's only one reason to fight for a ruling like that: to hide from churchgoers the amount of cash the church gave Coy to go away. The case reeks of political favoritism. "These guys have been covering for Coy for a long time," Newnham says, "and they're still covering for him now." (Judge Bailey didn't respond to messages from New Times to comment on this story.)

If Coy's resignation stunned his followers, it hasn't hurt Calvary Chapel Fort Lauderdale much in the long run. The church still claims about 20,000 members, and on a recent Wednesday night, thousands of them poured in for a service led by Pastor Sauder, Coy's replacement.

The chapel's grounds are more expansive than those of many colleges and brim with high-end features: an Astroturf soccer field, a huge playroom stuffed with kid-size toy airplanes and plush animals, even a fine-dining restaurant where sermons and musical performances are live-streamed as guests feast on cooked-to-order steaks.

In the huge sanctuary, a ten-piece band — including four guitarists, a drummer surrounded by glass sound walls, and two keyboardists — rocked out in front of a laser display that wouldn't be out of place on a Justin Bieber tour. As churchgoers held their hands up in ecstasy, Sauder read from Matthew and promised that Jesus was ready to heal.

"If you're broken, Jesus will be gentle with you in your anger and disillusionment," Sauder said. "If you're angry or you're disillusioned or you're fearful, if you embarrass yourself or you disappoint yourself... he can take all the mess and turn it into something beautiful."

Coy certainly paid a heavy price for his infidelity: His family has broken to pieces, and his chapels packed with thousands of adoring fans have been replaced with a half-full nightclub in Boca.

But Newnham says the pastor still has more to answer for — especially because his sources say Coy has been trying to mobilize investors to start a new church.

"He's contacted many former associates to try to get funding. There's no question he wants back in the game," Newnham says. "We need to stop him. In my opinion, if he did this [to one victim], it's just a question of how many others are out there. He can't be put in a position of power ever again."