Miami New Times, celebrating its 30th anniversary, has employed scores of writers since it began publishing in 1987. It has evolved from a small, scrappy weekly into a web-focused news and culture phenomenon that equals and often bests all other local media (even you, Mother Herald!) in reporting, writing, and telling the story of America's weirdest big city.

In honor of New Times' birthday and the Miami Book Fair, which opens this week, we assembled a list of 30 writers who have gone on to author volumes about everything from terrorism to baseball to Prince to Gander, Newfoundland. They have won Pulitzer Prizes, become foreign correspondents, and written tomes that will endure through the ages.

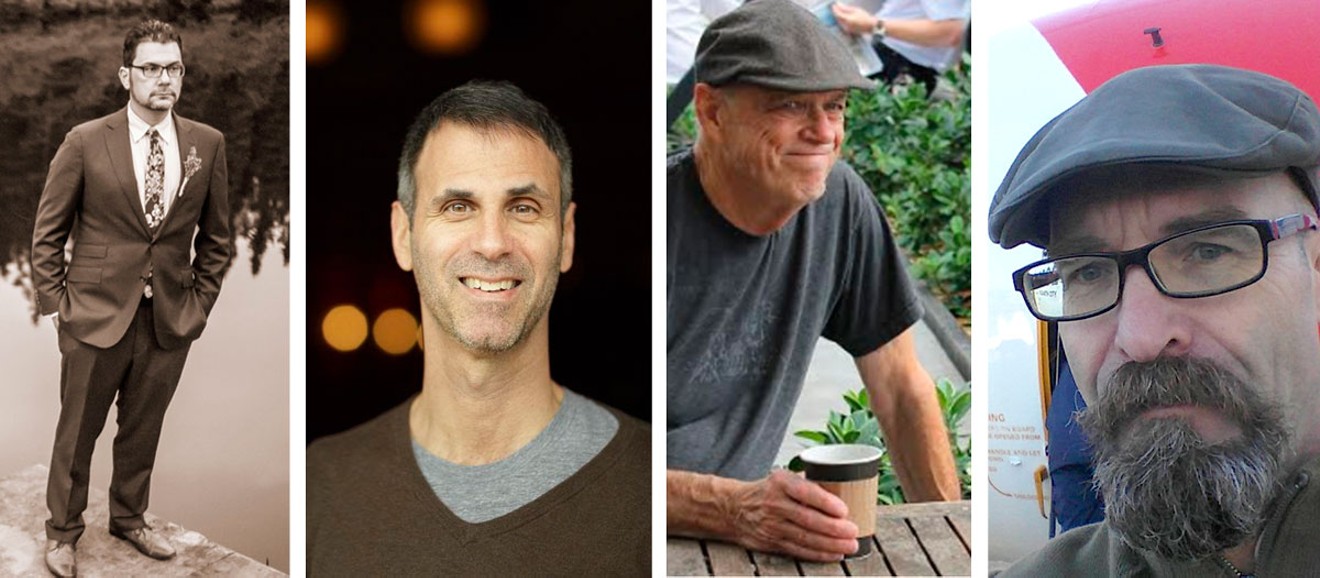

We asked each of them to write a short piece, and most answered the call. Together, they tell the story of New Times and of a writing style that has, in some ways, come to define Miami. Some of them, including Ben Greenman, Luther Campbell, and Jim DeFede, will tell their tales at the book fair Sunday, November 19, at 4 p.m. on Miami Dade College's Wolfson Campus (300 NE Second Ave., Miami; Building 7, First Floor, Room 7106).

Ben Greenman, 1990–98

We tried to put an innovative spin on the news, to invent new kinds of pieces. We were a weekly newspaper filled with journalists who were also comedians or authors or performance artists.

Once, when tourists were being killed or carjacked because thieves could spot their rental cars, we made (and pretended to sell) a Rental Car Conversion Kit to protect visitors.

We faked a new Bruce Springsteen album — we wrote lyrics, imagined songs, and reviewed it. (That piece got picked up nationally.)

My favorite: The Miami Beach Police Department once sent out a crime-scene team to document candy bars and other trash in the police parking garage. Big waste of public money. We did a piece, "Unsolved Mysteries, Dateline Miami Beach," that was fun to write, funny to read, and effective advocacy journalism: It made MBPD aware it was being watched, and angry to boot.

(Greenman is now an author and editor; bgreenman.com.)

Steve Almond, 1991–95

The stupidest thing I ever did as a reporter — it's a long list — was to almost get four little kids killed. I was working on a long piece about the James E. Scott Homes in Liberty City, the moms and kids who lived there.

As part of my reporting, I got in the habit of taking a bunch of kids out for excursions. One day I drove them down to the zoo, and on the way back, I ran out of gas right on I-95. I maneuvered get my shitbox pale-green Tercel onto the shoulder of the road. Then a torrential downpour began. Every time a truck roared by, sheets of water blasted the windows.

The kids were terrified. I was terrified. This was before the age of cell phones, so the only thing to do was climb down the embankment and wander around Overtown trying to find help. Two guys eventually agreed to buy me a gallon of gas and drive me back to my car (I paid them $40). It took me a half-hour to locate my car because this was an especially chaotic stretch of I-95 and it was nearly invisible in the monsoon.

When we finally found my Tercel, two of the kids were in tears. The guys who had delivered me were horrified.

"You could have gotten them boys killed," one said soberly.

He was right. If a police car had spotted my vehicle and pulled over to check it out, I might have faced a criminal charge of child endangerment or even kidnapping. But I got lucky.

It was a lucky age for New Times in general. The talent in the newsroom was mind-boggling: Sean Rowe, Kirk Semple, Kathy Griffin, Jim DeFede, Ben Greenman, Greg Baker. I miss them all!

(Almond is now an author and father. His latest book, Bad Stories, will be out in spring 2018; badstories.org.)

Mike Clary, 1991–2003

Over the years, I wrote many stories for Miami New Times, and most of them involved no danger or derring-do whatsoever. The list includes reports on the psychiatric ward at the Miami-Dade County Jail, a bloody gang war in North Miami, and a fast drive across Cuba from Havana to Bayamo with a family returning home with the body of a relative who had died on a visit to South Florida. But the closest I ever came to dying for New Times occurred in 1997 when reporting a story on the endangered American crocodile, "Chomp in the Swamp."

It was not the crocs that posed the danger, however; it was the weather. After a fast-forming thunderstorm caught two University of Florida scientists, a photographer, and me in the middle of Florida Bay, we sat like doomed ducks in a 15-foot open boat, waiting for our skulls to be split in two by one of the crackling lightning bolts raining down as if from an angry Zeus above.

Spoiler alert: We all lived. But the experience was very close to terrifying. Afterward, when the sun reappeared, I was annoyed that the scientist had put us into that situation. "We could have been killed," I cried. But he had been calm throughout the celestial terror attack, and he was calm afterward as he brushed aside my pathetic whining. "We're safe now," he said. "But the crocodile is still endangered."

(Clary is now a general assignment reporter for the Sun Sentinel.)

Robert Andrew Powell, 1994–2001

Not long after I joined the staff at New Times, as I worked on one of my first stories, I called the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta. It was just a fact-check, some very small thing. I left my name and number and what I was calling about.

Not two minutes later, I was called back by the head of the CDC, the top guy in charge. "We are aware of problems in this area," he told me. Um, problems? What? I thought, before proceeding to ask only my little question. When I thanked him and moved to hang up, he sounded confused and worried.

At my desk, while I was typing up my notes, it took me a few minutes before I realized the obvious. He must have thought I was with the New York Times. And there must have been something scandalously wrong up there. And there might continue to be a scandal to this day, for all I know. That anybody returned my call at all was the tip-off. We were granted very little respect at New Times. There was no institutional pull. No cachet. People tended to dismiss our stories, if they didn't like them, by pointing out that our "tabloid" largely consisted of strip club ads. The Miami Herald pretended we didn't exist.

That status made it harder to report, certainly. But it was also a lucky way to start out in journalism. Our stories had to be bulletproof. Our investigations needed to truly get the goods in a way that could not be refuted. Our features had to be written better than anyone could have expected. Many of the stories we wrote back then still hold up to this day. And a shockingly large number of writers from the paper have gone on to do respectable things in quite respectable places.

I guess one of us should probably look into the CDC. There seem to be some problems up there.

(Powell is now an author who lives in Miami Beach.)

Jake Bernstein, 1997–99

Joining Miami New Times in 1997 felt to me like being a rookie stepping onto a field of all-stars. Editor Jim Mullin had assembled an extraordinary crew of gifted journalists who were having a grand time tormenting the powerful, plumbing the depths of Miami's quirkiness, and entertaining the hell out of readers. Their pleasure flowed through their writing. It was irresistible.

One of the standouts in this group was Sean Rowe. Seductive. Arch. Handsome. He had a devil-may-care attitude, a perpetual wink that suggested he kept a fascinating world in his back pocket that he'd be happy to show you. He once drove his car down Biscayne Boulevard while tossing his business cards at the sidewalk like a fisherman casting his net into the sea.

He served up quotes like beautifully marbled steaks. Sean had a wonderful eye for nuance even though his characters tended to be billboard-tall personalities. Like his patter, his prose sucked you in and would not let go.

By 1999, the dream team began to scatter. Sean's departure led to an epic anecdote. A final debauch at a Fort Lauderdale tavern ended in the early-morning hours with Sean and a few colleagues stumbling elsewhere for more. At a railroad crossing, the group spied a fast-approaching southbound train. Sean got the bright idea to put a nickel on the track.

Over the roar of the engine, nobody noticed the northbounder coming the opposite way. The train clipped Sean, sending him flying 30 yards down the track, breaking his ribs, collapsing his lung, and fracturing his skull — but leaving him alive.

Who gets hit by a train and survives to tell the tale? I envisioned Sean drinking out on this accomplishment to a ripe old age. Alas, it was not to be. In 2010, his life was tragically cut short.

(Bernstein is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Secrecy World: Inside the Panama Papers, out this month; jakebernstein.net.)

Tristram Korten, 1998–2005

It's 2004 and I'm sitting down to eat dinner and watch The Wire in my Miami Beach apartment when the landline rings. "Korten? We know where you live. We know where your mother lives. You better knock off what you're doing."

I pause a beat. "What am I doing?" I ask.

"You know."

"Really, I don't." Then: "If this is about a story, tell me so I know which one to stop working on."

In reality, I knew which one because I was working on only one. And I had no plans of knocking it off. I just wanted the goon on the phone to confirm it.

"You know," he said again. "You wouldn't want anything to happen to Patricia in Rhode Island. You should go outside and check your car."

My 77-year-old mother indeed lived in Rhode Island — alone. The goon hung up. I spent the next minutes calling Miami Beach Police, the cops in the town where my mother lived, and finally my mother. Then the phone rang again. It was my buddy. "Did you go outside?"

"Been a little busy," I said.

At his urging, I stepped out. My silver Infiniti G20, the first nice car I had ever owned, had been splattered with eggs. At least one rock had dented the trunk. What is this, high school? I thought.

Anyway, the story ran. The goon's boss, whom I was writing about, left town. My editor gave me some money to fix the dent. And my mother: "That was the most excitement I've had in a long time," she said, laughing.

(Korten is now an author living in Miami Beach and is working on a book to be published in 2018.)