Today, legal marijuana flourishes in fields and greenhouses from Homestead to Tallahassee. Every day, new cannabis clinics hang green neon crosses in their windows, while millions of dollars pour in from global investors looking to get into the Mary Jane business. Weed has finally gone legit in Florida. So it's easy to forget the drug's long and checkered past in the Sunshine State.

Florida has always been a haven for the weird, the enterprising, and the drug-addled, so it's no shock the state has played a major role in America's tortured relationship with weed. The state's marijuana history has it all: big money, politics and propaganda, football flunkies and race car drivers, vampires and causeway cannibals, and even a near-death experience starring Jimmy Buffett and Bono.

'30s and '40s: Marijuana Madness

The cannabis plant isn't native to Florida, and even when the drug's popularity boomed during Prohibition, it took years for weed to find its way to the backwaters of the sparsely populated state. By 1931, though, the Key West Citizen reported the "use of marijuana, a drug made from a Mexican plant, is rapidly spreading in the United States. And, the pity of it is, there is little legislation to prevent this."

Aside from the less-than-subtle racism in calling a plant that originated somewhere in West Asia "Mexican," the paper was right about the laws. At the time, only a scattering of local legislation made smoking marijuana illegal. But plenty of prominent Americans wanted to see that change. One of them was Pennsylvania's Harry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Narcotics.

Anslinger whipped the nation into a fervor by portraying marijuana as a heinous threat. His weapon of choice was his "Gore Files," a series of 200 reports on violent offenses that had been carried out by supposed drug users. (Historians have since discredited 198 of the reports.)

Anslinger's best-known tale of gruesome marijuana crime came from the Sunshine State.

tweet this

Long before Florida Man became infamous on the web, Anslinger's best-known tale of gruesome marijuana crime came from the Sunshine State. In 1933, Victor Licata used an ax to kill his entire family in Tampa, where he slaughtered his parents, sister, and two brothers. Anslinger took his story national after authorities blamed the rampage on the fact that Licata smoked marijuana. Later, medical records revealed that Licata also had a history of severe mental illness and that cannabis likely had nothing to do with the bloody massacre. But Anslinger's rally cry against the "Devil weed" didn't regard facts as all that important.

Anslinger was also instrumental in drafting the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, which used the tax code to essentially make the sale of Mary Jane illegal by instituting onerous sales rules that could lead to five years in prison and fines of up to $2,000 — the equivalent of nearly $35,000 today. Just as the prohibition of alcohol was ending, dope's criminalization had begun in earnest.

By the '40s, full-on pot panic swept the nation, including its southernmost state. In February 1942, the front page of the Key West Citizen advertised screenings for the film Marijuana Madness with the description: "PARENTS!! See This Picture Now... Your Daughter May Be it's Next Victim! Youthful Marijuana Victims... A Fate Worse Than Death! True! A Puff... A Party... A Tragedy..."

'50s and '60s: Wah Gwan, Jamaica; Hola, Colombia

Despite the fever pitch of paranoia that movies such as Reefer Madness and Weed With Roots in Hell stirred in American parents, it was clear by the '50s that weed was here to stay. The beat poets and philosophers brought the drug into the mainstream, and in South Florida, that cultural shift was especially noticeable as the state's population began getting younger. Florida was no longer a scattershot of resort towns and retirement homes. In 1964, New College of Florida was founded, creating one of the most liberal universities in the nation and a haven of intelligent young people smoking weed in conservative Sarasota.

Florida was ahead of its time on marijuana culture. In 1968, a whole year before Woodstock, the Miami Pop Festival staged two huge concerts featuring the key hippie figures. During two days in May and three days in December, the festivals drew 120,000-plus people to see performers such as Jimi Hendrix, Joni Mitchell, Marvin Gaye, and Fleetwood Mac.

A year later, only a few months after Woodstock made hippie culture mainstream, came the inaugural Palm Beach International Music & Arts Festival. It would also be the last Palm Beach International Music & Arts Festival, because the show was a disaster. The weather took a turn for the worse, and when the rain started coming down and the temperature fell into the 40s, people began tearing down outhouses and using the timber for firewood. According to the Palm Beach Post, the 40,000-person event saw 130 drug overdoses and 130 drug arrests. Clearly, the counterculture had made it to the Sunshine State.

While the West Coast had plenty of marijuana supply coming in from Mexico, East Coasters began bringing back herbal souvenirs from the Caribbean — specifically from Jamaica and Colombia. One 1956 article from the Miami News described a 22-year-old from Jamaica who'd been caught trying to sell "563 grains of marijuana" (because pot was measured by the "grain" back then) and sentenced to two years in jail. When the man's lawyer pleaded for leniency, the judge rejected the request because "foreign crewmen aboard ships entering the Miami port constituted one of the chief sources of illicit drug imports into this country."

Soon the stories escalated to smugglers with hundreds of pounds of pot. The night of December 5, 1969, Inspector Francis Napier, a 31-year veteran of the Miami Police Department, was arrested while on duty for his part in a $100,000-a-week marijuana racket. That same night, one of his confederates was detained for having 400 pounds of weed in the car, and by morning, their other partner was arrested at the warehouse where they had stashed 1,000 pounds of Jamaican dope. According to the Fort Pierce News Tribune, an assistant U.S. district attorney said it was "the single greatest seizure of marijuana in Miami's history." By the end of the '60s, Florida was ready for its star turn as the nation's pot-smuggling capital.

'70s: Smugglers' Paradise

By the '70s, smugglers began hauling in marijuana not by the pound, but by the ton. Sneaking pot across the border into Florida became big business — the kind that didn't go unnoticed by the feds, especially when the biggest weed mules weren't exactly subtle.

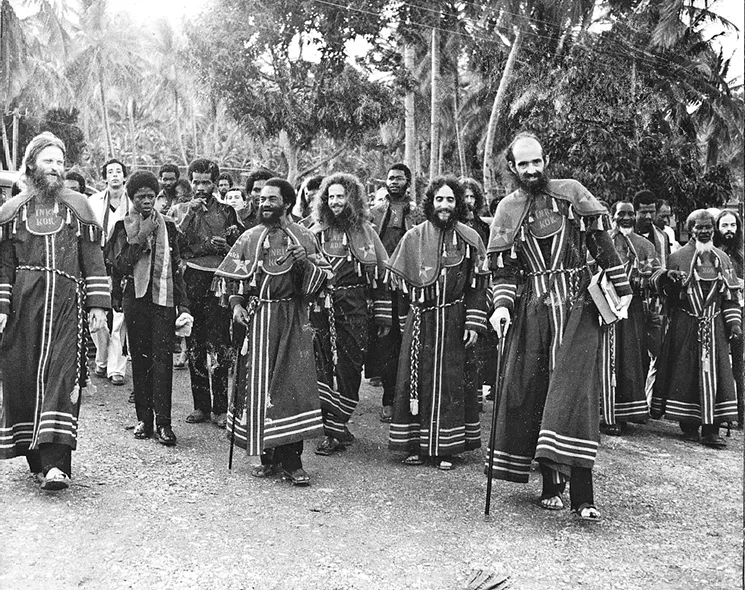

Take, for instance, the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church of Miami Beach. Founded by Thomas Reilly, who went by "Brother Louv," and his associates (a group of white guys who went to Jamaica and found God, ganja, and a snake-oil salesman/preacher named Edward Seaga), the so-called church set up shop at 43 Star Island, pissing off the wealthiest people in Miami Beach. Suddenly, their ritzy neighborhood was invaded by a bizarre commune participating in their holy sacrament of smoking weed night and day. In a 1979 CBS Evening News report, Dan Rather noted that many observers considered the Coptics to be "a fraud, a group of rich dope heads who have been allowed to laugh at the law and get away with it."

What they were getting away with was importing millions of dollars' worth of Mary Jane from Jamaica. They owned thousands of acres of fields on the island and even had their own shipping company and freighters to move the drugs, which they argued were a constitutionally protected part of their religion. In 1979, the same year Rather's program televised images of half-naked children in the group playing on the floors of smoke-filled rooms, the top-ranking members of the Zion Coptic Church were indicted for smuggling more than 100 tons of marijuana. Brother Louv eventually landed 15 years in federal prison and served a dozen before getting out in 1994.

Many considered the Coptics to be "a fraud, a group of rich dope heads."

tweet this

The church was just the weirdest face of a booming gray market of pot smuggling in South Florida. In 1978, Robert Platshorn and Robert Meinster were indicted for running what prosecutors called "the biggest and slickest" smuggling operations in history. The press dubbed them "the Black Tuna Gang" after their radio code word for their illegal product.

According to the DEA, the group attempted to transport around 500 tons of Santa Marta Gold from Colombia to South Florida throughout the '70s, at times even operating out of the presidential suite of the Fontainebleau Miami Beach. They were nabbed in the first joint venture by the FBI and the DEA, which the agencies touted as one of the greatest victories in America's War on Drugs. Platshorn was hit with 64 years in prison. He was released in 2008 after serving 28 years, making him one of the longest-serving prisoners on marijuana charges.

By the end of the '70s, Florida was not only importing mass quantities of ganja, but also becoming notorious for its homegrown weed. "Gainesville Green" came to be considered one of the best cannabis strains in the nation. In 1979, the Pensacola News reported that "it has a reputation as a very potent marijuana and tends to bring the same price as good Colombian pot." During his 1979 performance at University of Florida's annual Gator Growl, Bob Hope even joked about the local delicacy: "Honestly, I just found out what Gainesville Green is. I didn't know you smoked it. I was going to putt on it. Now I know what they mean by higher education."

'80s: Scorched Earth

After Ronald Reagan's election in 1981, the War on Drugs ramped up to new levels of insanity. And the Sunshine State went full-on Rambo in attacking Mary Jane.

In 1982, the Florida's First District Court of Appeals ruled that the smell of marijuana amounted to probable cause for police to search cars. By the next year, Florida became the first state to decide to spray marijuana fields with the chemical paraquat. The United States had persuaded Mexico to try the extremely toxic herbicide to kill the weed that growers provided for a huge part of the American market. The problem was that the growers didn't give a shit whether their cannabis was covered in poison and continued to harvest and ship tainted pot to the States. Once health officials warned that Americans were bound to get sick from smoking the now-toxic weed, the U.S. realized its plan might have been slightly flawed.

But that didn't stop Florida from giving it a shot in Red Bay, a little Panhandle town between Panama City and the Alabama border. Neither did the two lawsuits the state had to fend off from marijuana activists. In fact, Chevron Chemical Corporation, the company that produced paraquat, came out in support of one of the lawsuits because it didn't want to be held responsible for poisoning American pot smokers.

As a Miami Herald article in 1983 reported, by the time Florida quietly abandoned the use of the herbicide, "environmental concerns, the fear of more lawsuits, and — ironically — logistical inconvenience [had] rendered paraquat basically more trouble than it [was] worth."

The sleepy fishing village was now one of the most corrupt cities on Earth.

tweet this

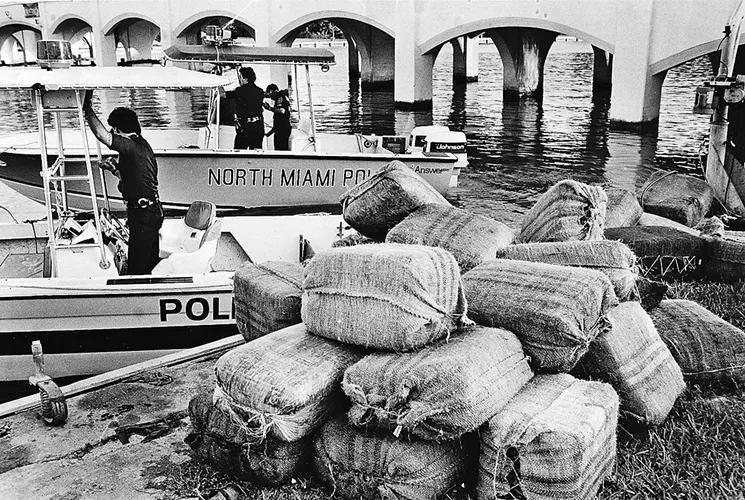

Few places in America were hit as hard in Reagan's War on Drugs as Everglades City, a small town 85 miles west of Miami on the southern tip of the peninsula. The most important piece of Everglades City's economy dried up when the feds banned commercial fishing in Everglades National Park in 1985. So the town found another niche: With its little airstrip, isolation, and plenty of fishermen who knew how to navigate the labyrinth of swampy waterways, Everglades City became a major drop site for smugglers looking for a place to leave the loads they flew in from Colombia. Rather than pulling up crab traps or reeling in bowfins and catfish, the local fishermen began hauling bales of weed, which they called "square grouper."

At the operation's peak, they fished upward of 75 tons of marijuana a week out of the River of Grass, keeping many townsfolk gainfully — if not legally — employed. So when the FBI and DEA carried out "Operation Everglades," the climax of a two-year investigation into the town's shadow economy, the effects were devastating. In 1983, the feds arrested 28 people in a community of only 600. Over the next several years, the agencies would make more than 300 arrests in the rural area and confiscate hundreds of fishing boats that had long been the backbone of the community's economy.

What had once been a sleepy, out-of-the-way fishing village was suddenly notorious for being one of the most corrupt cities on Earth. But Everglades City was far from the only town in Florida living large in the drug game. In 1988, the Miami Herald revealed cannabis was the second-biggest crop in the state after citrus fruit and raked in upward of $400 million per year.

'90s: Vampires, Jimmy Buffett, and the End of Prohibition

In the '90s, Florida finally began to follow a national trend toward a more progressive, tolerant perspective on pot. But this is Florida, so there was also a very dark side of marijuana mayhem.

One of the oddest, most brutal tales came in 1996, when John Crutchley — who was known as the Vampire Rapist because he was suspected of not only raping and murdering 30 women, but also of draining their blood — was inexplicably released from prison in Brevard County. In 1986, he'd been convicted of kidnapping and raping a teenage hitchhiker but received only 25 years and was paroled after just ten.

The very next day after Crutchley's release, he tested positive for marijuana, violating not only his parole but also Florida's three-strikes law. The result was life in prison without the possibility of parole. Let that sink in for a moment: Crutchley served only a decade behind bars for imprisoning a teenager, raping her, murdering her, and draining her blood — and then got life for smoking some weed. Florida justice is fickle.

That year, Florida's homegrown bard of the bud nearly died over a case of mistaken drug-smuggling identity. On January 16, Jimmy Buffett flew his personal seaplane, the Hemisphere Dancer, to Negril, Jamaica, with Bono, as well as Bono's wife and their two young children. The plane was taxiing along the water just off the coast when Jamaican authorities mistook it for a drug-running crew and decided to shoot first and investigate later. The plane was hit, but somehow nobody was hurt. Buffett went on to write the song "Jamaica Mistaica" about the incident, explaining in the lyrics: "We had only come for chicken/We were not the ganja plane." Bono and his family were so terrified they fled Jamaica as quickly as possible. If Bono and Buffett hanging out hadn't been uncomfortable before nearly dying on a plane, it's probably safe to assume the friendship was uncomfortable afterward.

Buffett's lyrics explained the incident: "We had only come for chicken/We were not the ganja plane."

tweet this

A landmark shift in the public perception of marijuana came in 1990, when Kenneth and Barbara Jenks in Panama City Beach were found guilty of growing and possessing weed, which they used to cope with the symptoms of AIDS. At that point, only five people in the whole country had been granted medical permission to use marijuana by the Food and Drug Administration. The Jenkses appealed their conviction and were eventually acquitted in June 1991.

The same year, a man in Tampa who was paralyzed by a gunshot became the first person the FDA allowed to use marijuana to treat paralysis. But the very next year, the Bush administration outlawed medical testing or application of marijuana. Only 15 people had been given permission by the FDA nationwide by then.

Two years later, when the Clinton administration announced it would reconsider the ban, only eight of those medical marijuana patients were still alive. And in 1999, the Florida Supreme Court ruled that defendants in certain pot cases could argue the drug is a "medical necessity" — an important precedent in a decade that saw numerous medical journals and health institutions call for serious studies into the medicinal benefits of marijuana.

'00s: Zombies, Medical Marijuana, and Beyond

If there's one man who personally lived the shifting tides of marijuana policy in Florida this past decade, it's Ricky Williams.

The star running back signed with the Miami Dolphins in 2002 but only two years later abruptly retired after a second failed drug test. Williams wasn't doing steroids, though — he was smoking weed to help alleviate years of football-induced pain. In 2005, he returned to the Dolphins, only to get slapped with another one-year suspension for — wait for it — smoking weed. In 2007, the year he would eventually be reinstated with the Dolphins, Williams failed his fifth drug test. The media slammed him: The Miami Herald published an article simply titled "Flunked Out." Greg Stoda of the Palm Beach Post was particularly blunt, writing, "The Dolphins don't need to comment officially now that Williams yet again has failed them and himself by failing another drug test."

Fast-forward ten years, though, and Williams was a respected keynote speaker at the 2017 Southeast Cannabis Conference & Expo in Fort Lauderdale before hosting his own "cannabis-friendly" Super Bowl party. And no one batted an eye this time.

Williams' story illustrates how dramatically things changed in a decade, when Florida finally legalized medical marijuana and many of its big cities decriminalized small amounts of recreational weed. But once again, Florida being Florida means there have also been some seriously dark pot-linked chapters.

Just when myths of cannabis-crazed maniacs seemed to have become distant memories, Rudy Eugene made headlines. On May 26, 2012, Eugene, who would come to be known as the "Causeway Cannibal" and the "Miami Zombie," abandoned his broken-down car and walked west across the MacArthur Causeway while stripping off his clothes. He was naked by the time he came across a 65-year-old homeless man, Ronald Poppo. Eugene began beating him, tearing his clothes off and literally eating his face. When the police arrived, Eugene growled at an officer and went back to chewing on Poppo. The attack ended only when cops shot Eugene five times. Poppo survived but lost much of his face, including his nose and eyes.

The savagery of the attack led to speculation that Eugene must have been under synthetic drugs such as bath salts or flakka, but when his toxicology report came back weeks later, the tests showed only marijuana in his system.

In the end, Eugene's story showed that times really had changed. Very few tried to turn the gruesome assault into a new war on marijuana.

In fact, just over a year after the attack, Miami Beach became the first city in Florida to call for decriminalization. In a straw poll, more than 60 percent of Beach voters came out in support of decriminalization and medical marijuana.

Florida has awarded only 13 licenses to grow medical weed. Many are being held hostage.

tweet this

In 2014, the state Legislature passed the Charlotte's Web Medical Hemp Act, nicknamed for the strain of low-THC marijuana that the bill legalized for the treatment of terminal illnesses and severe seizures. That year, a constitutional amendment to legalize medical marijuana came up just short of the 60 percent it needed to pass, thanks to Las Vegas business magnate Sheldon Adelson pouring millions into a scare campaign. But in 2016, the amendment again made the ballot and this time passed with more than 70 percent of the vote. Medical pot was officially legalized in 2017.

But the law has been far from perfect. Florida was painfully underprepared for the demand: Although more than 30,000 patients had applied for medical pot cards by August 2017, the state's new Office of Medical Marijuana Use had only a dozen employees. To date, 93,000 patients have applied, but more than a third are still waiting for cards; statewide, only 1,269 physicians have qualified to treat those patients and register those who've yet to find a doctor nearby.

And for farmers and entrepreneurs looking to get into the new marijuana business, the situation is equally torturous. Florida has awarded only 13 licenses to grow medical weed; many are being held hostage by politically connected companies producing nothing and waiting to auction off the lucrative right to grow in the state.

Yet there's no doubt Florida's views on marijuana have evolved hugely in less than a century.

Victor Licata chopped up his family, and the nation descended into reefer madness, eagerly following the lie that Licata was a marijuana-fueled maniac into an age of prohibition. Eighty years later, when Eugene ate a man's face in broad daylight with nothing in his system but marijuana, Florida not only moved on but also pushed for medical marijuana legislation.

There is still room for weed to grow in the Sunshine State. This past February, Regulate Florida, an organization dedicated to making recreational pot legal, received only about 5 percent of the signatures it needed to add a constitutional amendment to the ballot for 2018. But considering national polls are showing the highest public support for recreational marijuana in 50 years, the group's activists say they'll try again in 2020.

Marijuana will likely become a multibillion-dollar industry in Florida by 2020. In a state where money talks, that change is not just progress — it's a pot paradigm shift.