Despite displaying work from eight women of Latinx and/or Caribbean origin and descent, Oolite Arts' next exhibition, "It Will Never Become Quite Familiar to You," draws its title from one of America's favorite 19th-century white dudes: Henry David Thoreau.

In his book Walden, Thoreau goes into great detail describing his modest bean-growing operation; the intimate movements of mice, birds, and squirrels; and his discoveries while walking in the countryside and reveling in his (exaggerated) isolation. As he mused during these walks, he marveled at the constant stimulation the landscape offered, even if his mind stubbornly returned to burdensome thoughts of society. "But it sometimes happens that I cannot easily shake off the village," he writes. "The thought of some work will run in my head and I am not where my body is — I am out of my senses... What business have I in the woods if I am thinking of something outside the woods?"

For Angelica Arbelaez, curator of the exhibition, the title speaks less to Thoreau's lust for separation and more to an experience of recurring newness. The theme of "It Will Never Become Quite Familiar to You" is exploration of both personal and ancestral lineage, which Arbelaez became interested in through her experience as a child of Colombian immigrants.

"This idea of familiarity is important for what the works in this show are trying to articulate," Arbelaez explains. "It’s kind of a beautiful way to describe that you’re always going to continue learning. When you’re trying to map your lineage out, you are going to be constantly learning new things because you are engaging with it in different points of your life.

"The goal isn’t to completely know. The goal is to understand that you will always be coming across new things and that will always inform who you are."

In Miami, that experience isn't exotic or unusual. Plenty of locals identify as American while living on a steady diet of mofongo and novelas. But Arbelaez was still surprised by how little the reality was directly addressed.

"It tends to be a very private thing... It’s not [a] part of a diasporic experience that’s shared very openly," she says. "I was hoping with this show, I could illuminate some of that and offer a sense of identification between people — like, Oh yeah, I know exactly what that feels like. Feeling out of place or wanting to understand where you’re from is very common among people."

It's a feeling that's familiar to Natalia Lasalle-Morillo, a Puerto Rican-born film and theater artist who has spent the past decade based in the United States. Her work in the show centers on Alvis Hechevarría, a Cuban émigré whom Lasalle-Morillo interviewed over the course of three years. The project was born out of an endeavor the artist undertook to interview her mother in order to re-create memories from her life. In Miami for residencies with the Miami Light Project and the Miami Theater Center, Lasalle-Morillo extended the work by exploring Alvis' journey from Cuba to the United States in her 80s. And though the artist feels strongly that the work is about and for Alvis, she also sees it as a story of her own transience.

"There is an in-betweenness that comes with being from this place," Lasalle-Morillo says, "an experience of constantly reorienting your relationship to the island and to the United States. I think all of the artists [in the exhibition] have a relationship to that experience — of borders, of lines, of being in the middle of something and trying to make new theories about what it’s like to be from a particular place."

For Michelle Lisa Polissaint, those theories revolve around similarly fraught notions of home. The Haitian-American artist has been hyperaware of her hyphenated identity and worked through the complexities of it in a series of photographs of her parents' home. Grappling with being both "not Haitian enough" and "not American enough" seemed only amplified by the reality of being black in the U.S. South.

"Home base is always a bit confusing for people of diasporic experiences," Polissaint says. "The series is about basically trying to find this connection to home or trying to consider what I am or am not allowed to claim as home." It becomes especially puzzling, Polissaint adds, when she considers her parents's confusion over her political organizing, even if it includes fighting gentrification in Little Haiti.

It's difficult not to ignore, in these stories of migration, the root of what drives people from their homelands.The same year Thoreau first released parts of Walden, a secret meeting of American ministers drafted the Ostend Manifesto, asserting the United States should acquire Cuba from Spain by any means necessary to expand slave-holding territory. More than 40 years later, the Spanish-American War would result in not only the establishment of Cuba as a "U.S. protectorate" but also the acquisition of Puerto Rico as a U.S. territory. Less than 20 years after that, the United States would attempt to occupy Haiti for the first time, successfully forcing the country to repeal a constitutional provision that made it illegal for foreign entities to own Haitian land.

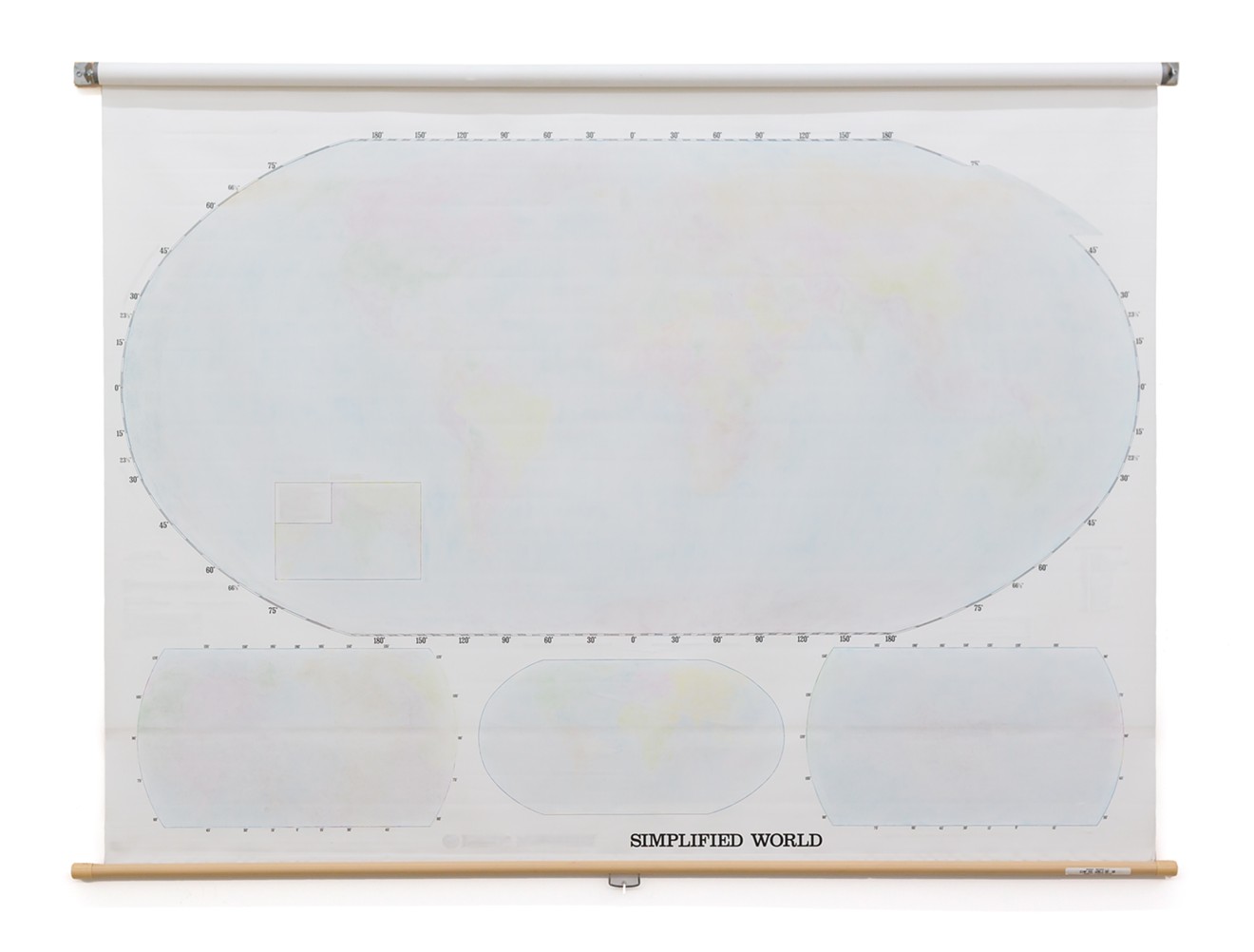

So even within artwork that appears deeply personal, the concerns of "the village" arise. This is why works such as Agustina Woodgate's Simplified World and Jesse Chun's Enunciating Silence And also fit, although they take a more conceptual approach. Heritage doesn't fit neatly into conceptions of identity or even of Thoreau's pioneering individualism.

"The core of the show is about these particular experiences, but in the grand scheme of the macro-American space, it’s about immigration," Polissaint says. "We keep our lives and our experiences so separate... Maybe this show can be an opportunity for us to think about how we’re all experiencing similar things and we need to stay connected to power through them.

"We can’t keep these insulated separations anymore," she reiterates. "These conversations are contributing to the larger issues of Miami’s communities needing to come together and face these issues that are about to hit the fan. It’s coming forward or coming to the surface more."

One hundred sixty-five years later, we're still contending with Thoreau's desire to disappear into the woods — or into our phones or our families or our personal expressions. Yet those escapes remain unfamiliar to us. So it's appropriate that, for Lasalle-Morillo, the point is to come to a new understanding of this constellation of ancestry, identity, and time.

"This generation has had a need for an inquiry, even if it’s accidental, to really define a new constellation," she says. "There is a process of making peace with the fact that it’s a new experience. I think right now, in some places in this country, there’s an authority to say that or an authority to question it — an ownership over questioning."

"It Will Never Become Quite Familiar to You." 7 p.m. Wednesday, July 17, through September 29 at Oolite Arts, 924 Lincoln Rd., Miami Beach; 305-674-8278; oolitearts.org. Admission is free. Hours are noon to 7 p.m. Monday through Friday and 1 to 6 p.m. Saturday and Sunday.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "19274298",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17482312",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482310",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18711090",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17482313",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]