UPDATE: In 2013, director Michael Bay released an adaptation of this three-part series. That same year, New Times revisited Pain & Gain and tracked down what's become of the Sun Gym Gang two decades later.

Miami businessman Marc Schiller disappeared from his Schlotzsky's Deli franchise in mid-November 1994. A month later, recovering from massive injuries at Jackson Memorial Hospital, he called private investigator Ed Du Bois. For weeks, he said, he'd been chained to a wall and tortured in unspeakable ways. He'd been forced to sign away his house, his investments, his bank accounts, his life insurance. In the end the kidnappers tried to kill him, and they nearly succeeded. Although blindfolded during the ordeal, he recognized one of his captors: a former business partner, a protégé. Help me, he begged Du Bois. He wanted his house back; he needed his money. But most important, he had to make sure they wouldn't find him and finish the job.

Marc Schiller spent the next week recovering at Staten Island University Hospital. On Christmas Eve 1994, he left the hospital and moved into his sister's Long Island home. He couldn't get across a room without using a walker. A simple thing like emptying his bladder was agony.

But he could remember nearly everything that had happened the month before: the burns and beatings, the forced signatures, the attempted murder. Most important he remembered the betrayal by Jorge Delgado, whom he had hired and made rich through generous partnerships. He called his brother in Tampa, and Alex Schiller called Delgado. Alex knew every disgusting detail of the abduction. He knew Delgado and his chums had swindled Marc out of various assets. He knew about the torture. And he was coming to Miami to avenge that suffering. Delgado had better grow eyes in the back of his head.

See also: Pain & Gain, From New Times Story to Michael Bay Film | Pain & Gain: Where the Real-Life Sun Gym Gang Characters Are Now

This posed a new problem for the Sun Gym gang. Schiller was alive and talking. They'd have to eliminate him once and for all. On Christmas Eve, Daniel Lugo, Adrian Doorbal, and Stevenson Pierre made a journey to Tampa. Schiller must be at his brother's house, they figured, and this time they'd kill him, no screwups. But as they watched the house, Alex emerged with a suitcase and took off in his car for Miami. The three wise men lost him on the Florida Turnpike. Lugo called ahead to warn Delgado, who spent a paranoid Christmas at home with his wife and their new baby.

Lugo and Doorbal had been making periodic visits to Schiller's Old Cutler Cove home since mid-November, when they'd ordered their captive to tell his wife to grab the children and flee to her native Colombia. Among the first possessions the gang removed from the vacated house were the contents of the safe: $10,000 in cash plus credit cards, the deed to the house and documents pertaining to Schiller's La Gorce Palace condominium, insurance papers, and his wife's jewelry.

By early January 1995 the gang was emboldened again. They'd heard nothing more from Schiller or his brother, and decided it was safe to move into the house. It was a swell, upscale place -- complete with a swimming pool, Jacuzzi, and an entertainment system that featured a 50-inch television -- a far cry from their usual digs. They'd taken care of the paperwork, and the house now belonged to D&J International, a Bahamian company Lugo had set up the year before. As new lords of the manor, they were living well indeed. Schiller was alive, an inconvenience to be sure, but even so they'd netted about $2.1 million in cash, real estate, cars, credit cards, and jewels.

Lugo, who still had to worry about the constraining terms of his federal probation, leased an $80,000 gold Mercedes in Delgado's name. Carl Weekes, the unemployed New York welfare recipient who'd moved to Miami to clean up his act, received about half the promised $100,000 payment for his role in the kidnapping. Stevenson Pierre would receive just $30,000. He had an attitude problem, they decided, and had been conspicuously absent during the most crucial episodes, including the final night when they'd tried so hard to kill Schiller.

Lugo was the point man in the plush new surroundings. He introduced himself around the neighborhood as "Tom" and explained, in terms that would alarm no one, that he and his colleagues were members of the U.S. security forces. Marc Schiller had run into legal trouble and been deported, along with his family. The house had been confiscated and now was government property. Tom and his crew would take care of its maintenance. Any strangers seen coming and going would be foreign diplomats, most of them from the Caribbean.

The gang acted neighborly, borrowing tools and returning them promptly. They began paying homeowner-association dues. Tom impressed one neighborhood couple by climbing up a tall ladder to change a front-porch light bulb two stories above their welcome mat. He asked another neighbor to accept delivery of packages delivered to the Schiller house if no one was home. The neighbor accepted twelve UPS deliveries and handed them over without question.

Lugo visited The Spy Shop on Biscayne Boulevard -- where three months before, the gang had bought stun guns, handcuffs, and other tools of the Schiller kidnapping -- this time to upgrade the home-security system. He decided on a $7000 closed-circuit video surveillance package that included waterproof outdoor cameras and sensors, and a 25-inch monitor installed inside the main living room. He hired gardeners to add shrubbery and a dense mass of bougainvillea. Increasingly the house was becoming a home. Weekes began sleeping over for days at a time. Sometimes Doorbal crashed there as well.

After dealing with domestic matters and putting in appearances at Sun Gym north of Miami Lakes, Lugo and Doorbal often headed out in the evening to Solid Gold, a North Miami Beach strip club.

Doorbal had his eyes on Beatriz Weiland, a Hungarian import and exotic dancer. Within the competitive environment of female pulchritude at Solid Gold, other performers said Beatriz -- with her big blue eyes, perfect complexion, and full-busted, slim-hipped body -- was one of the most beautiful women in the world.

Lugo set his sights on one of the strippers, too. He'd become enamored of Sabina Petrescu, a 25-year-old dancer who'd modeled for Penthouse. In 1990 she'd scored runner-up in the Miss Romania contest and now longed for life as an actress in the West. She flew from Bucharest to Moscow to Havana to Mexico City before entering the United States in the trunk of a car. For a while she worked as a cocktail waitress in San Diego, until a talent scout approached her about modeling gigs in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and New York. The assignments had all required Sabina to remove her clothes, usually while she danced on a stage. Eventually she wound up in Miami.

The two men certainly had the physiques to match their dream girls: They were incredibly strong, with muscles developed to almost monstrous proportions. Lugo had a broad forehead, brilliant smile, and dark-stubbled jaw. He possessed tremendous charm and a great deal of money: a million already from an old Medicare fraud scheme and now all of Schiller's assets. Although Doorbal was shorter than Lugo, he too had the build of a professional weight lifter, his muscle striations enhanced by his dark skin. He sported a thick head of wavy black hair that fell almost to his waist. Indeed Lugo's sidekick from Trinidad resembled some carved Caribbean virility god.

It was on Super Bowl Sunday that Beatriz told Sabina to go to the Champagne Room; there was someone who wanted to meet her. The Champagne Room was an elevated area within the club that separated the big spenders from the proles below. The guys in the cheap seats tipped with ones and fives as they drank $7.50 beers. Fifty dancers circulated at floor level, offering to perform $10 table dances. But up a few red-carpeted steps, drinks went for $15 and dances cost $20. There was more cuddling and nuzzling -- it was expected and allowed -- in the demimonde of the Champagne Room. Here most of the high rollers, an assortment of pro athletes, drug dealers, tourist businessmen, arms merchants, mobsters, and B-movie actors, were surrounded by several girls. You could buy a bottle of champagne for $1000. Guys who wanted to show off burned $10,000 in an evening easily.

Sabina remembered Lugo. He liked to slip dollar bills into her garter belt while she danced in a cage. Now, surrounded by a phalanx of provocative strippers, he was telling her he only wanted to talk. He was in the music business, he said, and wanted to feature her in a video he'd be filming in London. As the conversation progressed, he periodically handed her twenties. His tab that night ran about $400. When he said goodbye, she gave him a kiss. It was a start.

Within a week they were dating, and soon a relationship bloomed. Lugo warned Sabina that the other men at Solid Gold just wanted to take advantage of her. By February he had her ensconced in a one-bedroom, $800-per-month townhouse apartment that overlooked Main Street in Miami Lakes. Sabina wouldn't have to dance naked anymore. He'd take care of her. In the years since his divorce, he said, he had never felt so close to a woman. They began living together. (It was convenient for Lugo; he could drive just a few miles and be back home with his pregnant wife, Lucretia Goodridge.)

At first everything went well. Something like love, or maybe love itself, flowered. But Sabina didn't understand Lugo's odd hours, his occasional trips to the Bahamas. Why would a music-video producer need night-vision binoculars? And what was happening with that London video shoot he'd promised? She was growing bored in her gilded cage. There had to be more to do than shop and see her hairdresser.

Sabina's frustrations persisted; she demanded an explanation. "Look, if you're ever going to understand me," Lugo told her at last, "if this relationship is ever going to be real, you've got to understand my work. I'm with the Central Intelligence Agency." He'd gone through harrowing missions. One fell apart in a London hotel, and the Company left him on his own to survive on leftovers from room-service trays. On another CIA job in Hong Kong, he'd had to live for a week in a tree.

Lugo swore her to secrecy, and the beautiful Sabina, raised in Romania on a steady diet of American movies, was happy to oblige. A fan of action thrillers, particularly James Bond films, she now had her own real-life man of international intrigue. The spy who loved her even gave her a specialized code for her beeper: When she saw "007" appear on the screen, she knew Lugo was trying to contact her.

By now Adrian Doorbal also had moved nearby, to a two-story townhouse apartment a block away on Main Street. This, Sabina learned, was no coincidence: Doorbal, too, worked for the CIA. Lugo told her the Company figured it was smarter to have the team in close proximity in case they had to act swiftly. And when the guys disappeared for a few days now and then, it was because they were constantly on call; they had to report to headquarters in Langley, Virginia, at a moment's notice. They had no say in when or why; the life of a secret agent wasn't always glamorous.

Doorbal hadn't yet scored a date with Beatriz from Solid Gold, but he did have a steady girl. He'd been dating Cindy Eldridge, whom he'd met at Sundays on the Bay restaurant in Key Biscayne nine months before, on the occasion of her surprise birthday party. The 31-year-old Boca Raton nurse, a pretty blond fitness enthusiast, was taken with the stranger she chanced to meet at her party. And why wouldn't she be? He was a personal trainer, he told her, and co-owned a gym; he was interested in nutrition and bodybuilding. They both liked fast cars, too. Cindy had a red Corvette.

The personal trainer and the nurse had begun dating right away. Soon Doorbal proposed marriage, but Cindy declined -- she was older than he, and they didn't really know each other well enough. The commute between Boca and Miami limited their contact, but Doorbal saw her most weekends and sometimes during the week. Still, she didn't know the real sacrifices he was making for their relationship, those visits he crammed in between Schiller's beatings at the warehouse.

That winter of 1995 their problems began. Cindy wanted to move to Miami so they'd have more time together. But by then Doorbal was living on Main Street and playing the CIA agent for Lugo's girlfriend. (Besides, the distance gave him time to pursue Beatriz.) And there were more problems: Doorbal began having mood swings. He'd abruptly change his mind on any manner of subject. Worse (and there was no delicate way for her to bring this up), he was a flop in the sack. His libido was limp. But Cindy attributed these dark clouds to his steroid use; for bodybuilders it almost was an occupational hazard. She guided him to Dr. Eric Lief in Coral Springs, who specialized in treating long-term steroid abusers with hormone therapy. But the day finally came when Doorbal told her he just couldn't see her again. She was devastated.

While the Sun Gym gang was setting up house in Old Cutler Cove, Miami private investigator Ed Du Bois, who'd advised Schiller to check out of Jackson Memorial Hospital and leave Miami, received a phone call from New York. He was surprised but glad to learn Schiller was safe and healing.

Schiller was on his way to Colombia, to rejoin his family, but wanted to hire the detective to look into his kidnapping. Du Bois told him to write down everything he could remember about his abduction and torture, and to send any documentation he could gather.

A few days later Schiller flew to Colombia. Still on crutches, he was a mess physically and mentally. He'd lost 40 pounds and was down to 120. He had nightmares of that helpless, horrific month in the warehouse. He'd erupt in crying jags in the middle of everyday events. As he convalesced he also tried to put his financial life back together. With the help of his Miami attorney, Schiller discovered momentous changes in the family's lifestyle. There were outrageous charges ($80,000 worth!) on their credit cards: all phone orders, and not one made by him or his wife. His Schlotzsky's Deli franchise had been dissolved. The house now belonged to a Nassau, Bahamas, corporation he knew nothing about. His offshore accounts, in which he'd kept $1.26 million in investments, had been cleaned out. His checking account was empty.

He began compiling documents that followed the transfers of his property to mysterious offshore companies and people he had never met. The MetLife change-of-beneficiary policy gave him a laugh, one of the few since his kidnapping. Sure, he'd signed the form, but his signature didn't even run along the line. It rose almost perpendicular, pointing like a rocket off a launch pad. Several of his canceled checks displayed similar strange signature alignments; he couldn't believe his bank had honored them. And just who was this Lillian Torres, to whom he'd signed over his two-million-dollar life insurance policy and the investment in his La Gorce Palace luxury condominium?

During Super Bowl week Schiller's letter arrived at Du Bois's office, detailing his brutal ordeal and his certainty that Jorge Delgado, his former business partner and friend, was involved. He also named Daniel Lugo, an associate of Delgado, as one of his captors.

Du Bois had no idea who those guys were, but the paper trail led straight to the heart of his professional and personal history. The documents attached to the letter -- copies of title and account transfers -- had been witnessed and notarized by John Mese, an old Miami Shores acquaintance. Du Bois called Schiller and told him that he knew John Mese.

"This guy Mese has to be involved in my kidnapping," said Schiller.

"I can't imagine that," Du Bois replied. John Mese?

He couldn't begin looking into the case until the following week, after the Super Bowl, when he'd wind up his work as the NFL's top security consultant for the Miami extravaganza. He attended the opulent Commissioner's Ball and walked the sidelines during the big game. But Schiller's tale filtered through the festivities. The man's lonely suffering was bizarre and unsettling.

John Mese was the starting point of the Schiller file. Du Bois knew him as an accountant, a former bodybuilder, the owner of Sun Gym, and a promoter of bodybuilding competitions. He'd known Mese and his family for 30 years through the Miami Shores Country Club and the Kiwanis Club. In fact Mese occasionally had used his detective agency. The two men cut similar figures in the intimate Miami Shores community. Both had attended Miami Edison Senior High School. Both were handsome, strong, hard-working, and prosperous. They had pretty wives and wholesome kids. For five years in the Seventies they'd had offices across the street from each other in the Shores' intimate business district.

Du Bois simply could not picture a dark side to him. If anything he thought Mese was a decent, harmless guy whose true passion, bodybuilding, sometimes intruded on his day job. He must have been conned. He couldn't have witnessed Schiller's signatures unless he was present at the warehouse where Schiller had been held captive and tortured. But if he was there, Du Bois wondered, how did he ever get hooked up with those guys? How could he have gotten mixed up in something as cruel and unsavory as the Schiller abduction?

Du Bois called Mese and asked for a meeting, adding cryptically that it might be the most important appointment of his life. "What, Ed, you're going to bring me a new client, like the NFL or the Dolphins?" Mese joked. Du Bois expected to wrap the whole thing up quickly.

The meeting took place on February 2, 1995, at Mese's Miami Shores office. At 57 years old, he was no longer the chiseled muscleman of old. He now resembled a white-haired Norman Rockwell grandfather poised over the Christmas turkey.

Mese didn't know anyone named Marc Schiller. Du Bois handed him Schiller's letter, studying his face as he read. There wasn't much to discern. "Sounds like this guy had a rough time," said Mese.

Did he know Jorge Delgado and Daniel Lugo? To the detective's surprise Mese said yes, Lugo was employed at his gym, and Delgado worked out there. Besides that, they were hard-working businessmen and clients of his. He'd represented both before the IRS.

A silence fell between the men.

"Ed, I still don't figure how I fit into all this," said Mese.

Du Bois handed him a copy of the quit-claim deed to Schiller's house, and Schiller's MetLife change-of-beneficiary form. Mese had notarized both. In all Mese had witnessed and notarized more than two million dollars of Schiller's assets in the past few months.

The accountant's memory suddenly improved. "Actually," he offered, "Lugo and Delgado brought in some Latin guy with a passport for ID." Maybe this was the man Du Bois was asking about.

"Did a woman come with him?" the detective asked. No, Mese said.

Du Bois then pointed to another signature on the deed, that of "Diana Schiller." And he produced a copy of her passport. She'd left the United States on November 18. But her signature appeared on documents dated November 23 and 24.

"John, how did you possibly witness the signature of a woman who was in South America that day?" Du Bois asked. "Was any other woman here impersonating her?"

Mese hesitated. Well, he said, his recollection was vague about the circumstances surrounding Diana Schiller's signature. Perhaps it was signed before he received the papers, or maybe something screwy had happened. He agreed to set up a meeting with Lugo and Delgado to straighten out the matter.

A second meeting was set up for February 13, again at Mese's Miami Shores office. This time Du Bois took precautions. If Lugo and Delgado had committed terrible crimes against Schiller, they were capable of anything. Early in the morning Du Bois rounded the corner past his house and stopped in to see his best friend, Ed O'Donnell, a veteran criminal lawyer. O'Donnell had worked as a major-crimes prosecutor in the State Attorney's Office before switching to private practice. Du Bois told him about the gang, the letter, the documents, his fears. If something happened to him this morning, he wanted the attorney to know the identity of those at the meeting, and the circumstances that took him there.

Du Bois also took care to hire a bodyguard.

Ed Seibert's career included stints as a Washington, D.C., homicide detective and an agent for the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. After retiring he freelanced as a security consultant in El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Colombia from the mid-1980s through 1991. He'd planned logistics for the Nicaraguan contras and worked as a ballistics expert and weapons instructor for pro-democracy movements. Now he maintained a quiet life in Miami and was active in his church.

As Seibert read the Schiller memo on the way to Mese's office, the brutality of the Sun Gym gang reminded him of his years in Latin America, where such incidents were the common consequence of business, ideology, or drugs. This doesn't happen in America, he thought. Then he adjusted his thinking: This is Miami. Everything goes. But like Du Bois, he noticed something odd -- there was no ransom request. Schiller, it seemed, was completely disposable.

As usual Du Bois didn't carry a gun. As usual Seibert carried two. The detective already had checked out the building's entrances with his own investigators, whose cell phones were programmed to speed-dial the police and emergency services. When everyone was in place, he and Seibert walked in for the appointment.

Mese asked Du Bois and Seibert to wait in the reception area; Lugo and Delgado hadn't arrived. A short time later Mese strolled through to announce Delgado was on his way. Du Bois pulled out a photo of Schiller and asked Mese if he looked familiar. No, Mese couldn't say for sure this was the guy who came to his office with the documents for notarization. "Ed," he laughed, "you know all those Latins look alike."

Delgado arrived alone and Du Bois quickly sized him up. His demeanor was meek; he possessed few if any of the ingredients that establish a strong first impression. He was thin even, certainly not the goon they were expecting. Mese made the introductions, ushered them into an empty office, and left.

Delgado asked to see Schiller's letter as well as the house deed and the change-of-beneficiary form. He took his time inspecting them before handing the papers back to Du Bois. "This is all over a business deal," he said languidly, as if he were dismissing the matter and there was nothing more to say. His tone, his attitude began to grate on the detective.

"Well, is it customary in your business deals," asked Du Bois, "to kidnap someone, keep them hostage for a month, beat them, torture them, try to kill them, and blow them up?"

"I'm not going to comment on that," Delgado replied, growing edgy.

Du Bois jabbed a thick index finger in Delgado's face. "It finally dawned on me as to what really happened here."

"Yeah, really? What?" came the challenge.

"Had you killed Marc Schiller that night, as you had intended, this would have been a perfect crime," Du Bois hissed. "You had his cash, property, cars, home, plus a two-million-dollar bonus if he died. You had his family leave the country, him playing a role about a young girl and a midlife crisis. You had his phone calls diverted from his home to the warehouse, where you had him chained to a wall."

No response.

"If he died you would have been successful," said Du Bois, now sneering. "But guess what, asshole? Schiller is alive and well, and we are going to put your ass in jail!"

Delgado flushed slightly.

Mese rejoined the discussion now, and Delgado, who suddenly was conciliatory and seemed to want out of the room fast, suggested another meeting. He'd bring in Lugo tomorrow to explain the whole situation. They'd meet at Mese's branch office in Miami Lakes.

The next morning at 9:00 Du Bois and Seibert arrived in Miami Lakes. The detective decided to drop his back-up team simply because Delgado had cut such an unimpressive figure. Outside the building he glanced at the tenant directory. A mortgage firm, JoMar Properties, was on the third floor. It was Delgado's company, a holdover from the days when he and Marc Schiller were partners.

Mese was late, and neither Delgado nor Lugo were there. Mese's office was open, however, so they went in. The reception room was dominated by a popcorn machine topped with a glass bubble, and chess sets everywhere -- wood, brass, marble, onyx. Du Bois beat Seibert in two quick games. Growing bored, the detective stepped out to the balcony for some fresh air. Seibert decided to take a walk through the office complex. He went upstairs to check out JoMar Properties. The office was closed. Odd for a weekday, he thought.

Mese finally showed at 10:30 a.m., and expressed surprise to see them. "Gee, Ed, what are you guys doing here?" he asked. It was as if he'd stumbled into fellow members of an Edison High School alumni group while touring Calcutta.

"Listen, John," began Du Bois, noticing that Mese was sweating. "We had a meeting scheduled at nine o'clock. We set it up yesterday, remember? Now where are Lugo and Delgado?"

Mese hastened to assure him the two were on their way. In the interim the detective could go over his client files on Sun Gym, take whatever notes he needed, and request photocopies of anything important. He escorted Du Bois and Seibert to a vacant room and seated them at a desk cluttered with an overflowing ashtray and two champagne glasses stained with the sweet residue of a cordial. Then he left them alone.

Du Bois quickly reviewed the papers, an unremarkable collection of corporate filings, nothing significant. Bored, Seibert began going through the trash can under the desk. He knew garbage could be golden. And sure enough most of the discarded paper contained references to Sun Gym and the Schiller abduction suspects. An envelope from Central Bank contained the January 1995 bank statements of Sun Fitness Consultants, Inc., located at the same address as Sun Gym.

"Look at this!" said Seibert gleefully. They begin to sort through the windfall, spreading papers out on the desk. Du Bois set aside some of the documents, and Seibert got up and locked the door.

Amazingly Mese had ushered them into the room Lugo used for his own office, the very room, in fact, where the gang had planned Schiller's kidnapping. Now it held damaging links between Mese and the abduction. Glancing at the champagne glasses and the ashtray, Du Bois believed two people had been up all night throwing this stuff away. They must have assumed the cleaning crew would be in later.

The candy store of evidence showed that in January 1995, the Sun Gym gang wrote various checks totaling $163,969.57. Du Bois was incredulous. "Now, how does a shit operation like Sun Fitness blow through almost 200 grand in a month?" he asked. The money had to represent a portion of Schiller's stolen fortune.

In part the payees included the cast of characters who starred in the Schiller abduction. Thirty grand alone went to Carl Weekes. The U.S. government also received a portion of the Schiller bounty: A cashier's check for $67,845 paid off Lugo's court-ordered restitution from a 1991 fraud conviction. (Lugo still was on parole and couldn't possibly explain the sudden acquisition of 70 grand on his Sun Gym salary. So his boss, Mese, had purchased the cashier's check. Mese attached a letter stating he'd paid that much for a software program Lugo created for the gym. Through old-fashioned money laundering, they moved the funds from Schiller's Cayman Islands offshore accounts to Sun Fitness Consultants to Mese's Sun Gym account to Central Bank, where Mese & Associates had an operational account and where Mese bought the cashier's check.

The mysterious Lillian Torres, Adrian Doorbal, The Spy Shop, and JoMar Properties also profited from Schiller's forced signatures. Du Bois and Seibert couldn't believe their good fortune. This was like striking oil with the thrust of a teaspoon. They began stuffing the papers into their jacket pockets until they realized there simply was too much product. They filled their briefcases and then unlocked the door. If Du Bois ever harbored doubt about Mese's involvement, it was now gone. He believed his old pal was the CFO of a torture-for-profit gang.

At last Jorge Delgado showed up, alone, and Du Bois, buoyed by Mese's colossal mistake, launched into his list of accusations.

Suddenly Delgado interrupted. "We're not going to talk about this anymore," he said.

"Well, then, why are we here?"

"Because we're going to give you Schiller's money back, the one million dollars."

That sounded as sweet as a confession to Du Bois. "When and where do we get the money?" Schiller, he knew, had no liquidity, and was in need of hard cash.

The return was conditional, Delgado explained. First Du Bois and Schiller would have to sign an agreement that they'd never repeat the story to anyone, certainly not the police. Then, and only then, Schiller would see the $1.26 million from the offshore accounts he'd signed over.

The detective agreed to talk to his client, and Delgado proposed a brief contract. The meeting was over.

Seibert grew even more serious on the drive back to Du Bois's office. Even if these guys could buy their way of out Schiller's suffering, he warned, they'd do it again to someone else. They'd gotten the taste. "The next time," he said, "they'll make damn sure they kill the person."

That evening, as a Valentine's Day present, Lugo presented Sabina with an engagement ring and $1000 in her bank account. And he gave her some good news: They were going to take some time off and go to Orlando. During the drive north, Lugo felt as lucky as a Super Bowl MVP. Not only was he at Disney World with a beautiful woman, but he'd received great news himself. He announced to Sabina the official end of his federal probation. Sabina didn't even wonder how he could be both on federal probation and a CIA agent; the contradiction eluded her. She was just enormously happy for Lugo -- happier even than he was, she said -- as they drove their rented convertible back to Miami.

But the appearance of Du Bois into his serene, post-Schiller existence had begun to rattle Sabina's man of mystery. One day he received a call from Lillian Torres, she of the two-million-dollar MetLife change-of-beneficiary form. An investigator from Du Bois's office had shown up on her doorstep, asking nosy questions. They'd made the connection, which hardly was a stretch, between her and Lugo. His ex-wife Torres had been in on the scheme. How long would it take for them to reach current wife Lucretia Goodridge, who had witnessed Schiller in captivity?

So outraged was Lugo that he called together his cohorts and railed against Schiller and the detective. They were ruining his life. His obsession with Schiller only intensified. One night he showed Sabina a purloined video of a birthday party Schiller had staged for his son, back when the family still lived in Old Cutler Cove. It was a big party, with clowns, cakes, decorations, and presents. "Look at my money!" Lugo complained as the tape played. "Look at that party, how he uses my money!"

By now Du Bois had laid out the gang's proposition to Schiller. But his client wasn't impressed. In fact he thought the offer was no more than a stall tactic while they tried to find him. He had no doubts they'd kill him if they did. On the other hand, he was desperate for cash. And he wanted to go to the cops. What if he could get the money and then go to the police? That way, when the guys were arrested, he wouldn't have to watch them use his money to pay off their lawyers.

Du Bois and Schiller agreed that if they were going to pursue the "payoff," they needed to consult an attorney. Du Bois went back to his friend Ed O'Donnell. The former prosecutor was stunned that Delgado would even ask for such an agreement. "What kind of bozo says to his attorney, 'This Schiller is accusing me of kidnapping him for a month, torturing him, and stealing all his money and property. It's a lie, but I'm going to pay the $1.26 million anyway?'" He wasn't even sure the gang could find a lawyer to draft such a contract, which would cause any attorney to see more red flags than Chairman Mao. More important, O'Donnell said, the "agreement of silence" was unenforceable. Besides, it was a confession Schiller could take straight to the police.

But the Sun Gym gang did find a lawyer: Joel Greenberg, a Plantation attorney in his first year of practice. What Greenberg didn't know was that Lugo, in what the gang considered a stroke of financial genius, had devised a scheme to bamboozle Schiller. He planned to alter the contract to read 1.26 million lire, instead of 1.26 million dollars, thereby reducing the payment to little more than $1200. When Greenberg was let in on the plot, he balked. He'd write the contract, yes, but he wasn't going to get involved with the ridiculous lira gambit. The young attorney did provide Lugo with a contract stripped of dollar signs; if Lugo wanted to add the lire, he could.

The days dragged on and drafts of the contract were faxed between the two camps. Schiller agreed to every new revision, but there was no money coming in. So Du Bois sent Greenberg a letter to warn him that unless the funds were forthcoming, he'd deliver to the Sun Gym gang "a civil RICO complaint so large I'll have to deliver it in a U-Haul." He would pursue the gang as an ongoing criminal enterprise, the type targeted by federal and state racketeering laws.

In mid-March, though, it was the Sun Gym gang that rented a U-Haul, to empty out the Old Cutler Cove house. Through his Miami attorney, Schiller filed a challenge to the deed now held by the Bahamian firm D&J International. With legal threats heating up, the gang knew it was time to get out with what they could.

For the heavy work, Lugo hired a Sun Gym weight lifter who, like Schiller's neighbors, believed the house belonged to Lugo. The bounty he carried out was immense; his load included the 50-inch Mitsubishi television, Persian rugs, bronze sculptures, leather couches, the bedroom furnishings, Cristofle silver, Lalique and Waterford crystal, the dining table, an $8000 buffet, the washer and dryer, a freezer, computers and video games, copiers and a printer, assorted camcorders and smaller TVs, the patio furniture and Jacuzzi, two bicycles, a baby stroller, and the faux Christmas tree and Hallmark ornaments. Even the family photo albums and videos.

They also took Schiller's favorite snakeskin briefcase and his $600 Cartier sunglasses, and Diana's Guccis, and all the kids' clothes. They even removed the light-switch covers. Finally they drove off with Diana's BMW station wagon (the gang enlisted the help of yet another Sun Gym weight lifter, who altered the car's vehicle identification number). It was a brazen haul, totaling more than $150,000, and that didn't include the BMW.

As soon as Schiller won back the title to his house (the gang decided they'd better not respond to his challenge) he sent Du Bois to have a look. The kitchen remained intact; there was even baby food in the refrigerator. Otherwise the place was bare.

It was eerie, this housecleaning job, thought Du Bois, as though Schiller and his family never existed. All the trappings of a lifetime were gone. The Sun Gym gang had wiped out the Schillers far more thoroughly than did Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Back then they'd lost only their windows and doors, and part of their roof.

The detective placed a call to Colombia to deliver the bad news. "What do you mean, Ed, 'cleaned out?'"

"Well, you've got a refrigerator," said Du Bois. "But you don't have any other appliances, there's no furniture, all the clothes are gone, they even ripped out your Jacuzzi."

"What about the paintings?"

"The walls are bare."

The goods ended up at Delgado's Hialeah warehouse -- the same warehouse where they'd kept Schiller chained to a wall all those weeks. Now the gang met to divide the bounty. Doorbal got the leather furniture and the large-screen TV. Lugo took the dining-room table and some paintings. He presented them to Sabina. A few days later, when she learned it all came from that bad guy Marc Schiller's house, she said she didn't want it. But soon after that, when she flew back to Romania to tell her parents she was happy, prosperous, and engaged, Lugo moved even more loot into their apartment.

When she returned from Europe, Sabina received yet another gift from her fiancé: a black BMW station wagon. With its new VIN number, Diana Schiller's Beemer now was street-legal. Sabina was thrilled, until the rainy day when she realized she couldn't operate the wiper blade on the rear window. A sushi restaurant was nearby, and she pulled in. She could sip on some sake, she figured, while she leafed through the operator's manual. But the first thing she saw when she opened the booklet was the name "Marc Schiller" listed as owner. Flustered, she drank more sake. This was unexpected, unwelcome information. She confronted Lugo later that night. Yeah, he said, the BMW used to belong to Schiller.

Meanwhile Du Bois's wife and their children began to notice bulky strangers sitting in cars, watching their Miami Shores house. You didn't have to be Sherlock Holmes, or even Watson, to find Du Bois at his Shores residence; he was listed in the phone book. But when a phone-company security supervisor alerted him that someone was trying to gain access to his records for calls to South America, he really began to worry. Did the gang think he could lead them to Schiller? He knew they were capable of anything if they wanted Schiller badly enough. And he knew they'd spent $12,000 at The Spy Shop not long ago. If they'd bought eavesdropping and surveillance equipment, were they using it on his family?

Negotiations for the return of Schiller's $1.26 million had gone nowhere; he still hadn't seen a dime. Du Bois had to admit his client was right: Lugo and Delgado never planned to return the money. The meetings and the faxes sent through Mese's office had been a stall. Now it was time to go to the police. He called Schiller first. Then he called John Mese and told him the deal was off.

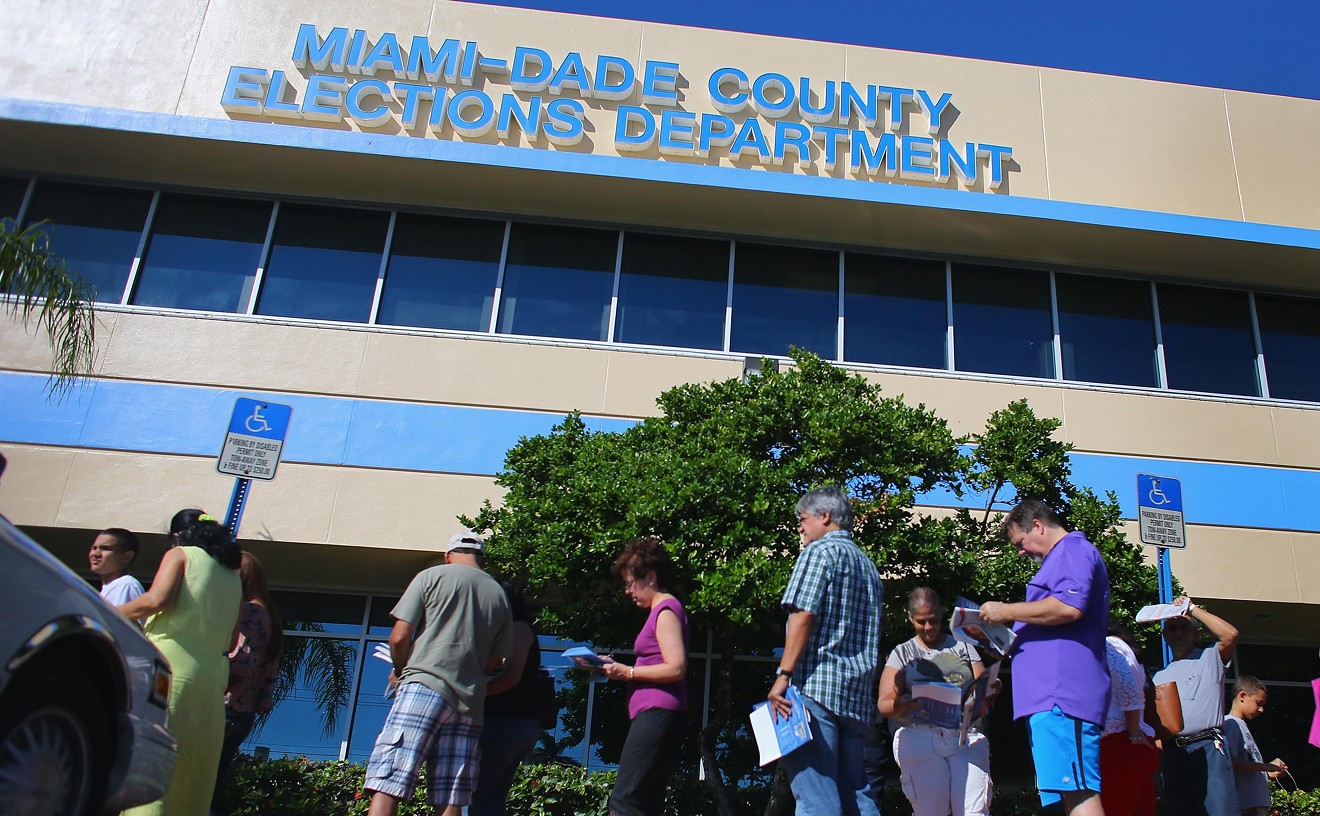

Du Bois called Metro-Dade homicide Capt. Al Harper, one of his Miami Shores acquaintances and a 27-year veteran of the police department. After Harper heard the horrific story, he called Metro's elite Strategic Investigations Division. SID conducted all major investigations involving fraud, drug trafficking, contract killings, criminal conspiracy, and organized crime. SID agreed to review the case.

Du Bois's next contact was with SID Det. Kevin Long. The private investigator didn't launch right into the details; he wanted first to establish Schiller as a credible victim. Would SID prepare a polygraph for his client? As a polygraph examiner since 1974, Du Bois knew this would be the most effective demonstration that Schiller's weird, brutal story was true.

Sure, Long said, and then sat back to listen as Du Bois went over the case and what he knew of the suspects. If Schiller agreed to come back to Miami, Long said, he would see him and take the complaint. No problem, said Du Bois, but Schiller was afraid for his life and wanted to make the trip as brief as possible. They set up a three-day interview window: April 18 to 20, 1995.

On Tuesday morning, April 18, Schiller flew into Miami from Colombia and checked into the Miami International Airport Hotel under an assumed name. He brought along a Colombian relative for protection, and walked straight from the airplane to Concourse E, where the hotel is located. That afternoon Du Bois met his client for the first time. The two men shook hands, and Du Bois noted that Schiller was thin but otherwise a physically unremarkable man, except for a deep burgundy notch on his nose, a souvenir of the duct tape that had been wrapped so tightly around his head during his captivity. Schiller was invigorated by the decision to go to the police. But he also was wary, afraid he might die in Miami.

At the SID office, they were met by Sgt. Gary Porterfield, who asked Schiller to wait outside while he talked to Du Bois in his office. Du Bois handed over a copy of the case file, then began the narrative of his investigation. As Porterfield took notes, Du Bois outlined the history: Marc Schiller disappeared on the afternoon of November 14, 1994. During his captivity, he signed over everything he owned to individuals connected with Sun Gym. On December 15 he reappeared, broken, in the emergency room at Jackson Memorial Hospital. Du Bois had information on the Sun Gym members: Daniel Lugo, Adrian Doorbal, Jorge Delgado; and on Sun Gym's owner, John Mese. Others were involved as well. They'd be easy to track down and question. He also gave Porterfield a twenty-page memo and canceled checks, deed transfers, accident reports, and hospital records. And he had a copy of Lugo's federal rap sheet and divorce documents.

An hour later Porterfield summoned Schiller to provide a statement. He too spent an hour with the sergeant. Porterfield promised to spend the next day investigating the case. They planned to polygraph Schiller on Thursday. The next day, however, Porterfield called with bad news. There were scheduling difficulties. Would Schiller stay over until Friday morning for the polygraph? Schiller canceled his flight and made a new reservation for Friday afternoon.

On Friday Du Bois and Schiller arrived at SID for the polygraph test. Instead Porterfield met them with more bad news: SID wasn't going to take the case after all; they'd decided to refer it to the robbery bureau.

The robbery bureau? Du Bois was dumbfounded. "Gary, are you kidding me?" he asked. "You're going to transfer a complex, nasty case like this to robbery, which is already dealing with 10,000 purse snatchings and smash-and-grabs? You're shit-canning this case. Why?"

Porterfield said his supervisor, Lt. Ed Petow, had concluded that the basic elements of the case were robbery. Yeah, Du Bois thought, and Oswald was guilty of illegally discharging a firearm in a public place. "Face it," he said, "the bottom line of almost every crime is an attempt to illegally gain money or property." But this case was brutally different.

Du Bois knew he'd just heard the death knell to any serious investigation. Worse yet, it would leave the goons on the street. They still had Schiller's money, but when that ran out, they'd snatch and torture someone else.

Porterfield led them to Metro-Dade Police headquarters, a couple of miles away, as Du Bois followed in his car. Schiller couldn't believe they'd blown him off after the information they'd provided.

"Hey, Ed, I mean ... robbery?" Schiller began. "This is kidnapping, attempted murder, conspiracy ... torture."

Du Bois tried to cheer him up but was in shock himself. In the short drive to police headquarters, the solid professional landscape he'd cultivated over the past two decades had metamorphosed into a surreal, receding mirage.

As Porterfield escorted them to the robbery bureau, Du Bois noticed a lone detective seated in the waiting area. The man was smirking at them and softly clapping his hands. Schiller went to his interview, and Porterfield walked off down the hall with the detective who'd just applauded their arrival. Du Bois approached the bureau's secretary. "Why was that detective clapping and staring at us?" he asked.

"Well, don't tell anyone I told you," she replied as she peered over her shoulder, "but SID called over here this morning and said we should expect an Academy Award-winning performance and story from Mr. Schiller today."

That's it, Du Bois, thought. This investigation is doomed. SID had poisoned the Schiller case. But why? He had to get outside for some air. He had to think.

It was there, on a balcony, that homicide Capt. Al Harper, who'd first suggested the case go to SID, came upon him. Du Bois was pacing, confused and angry. "What are you doing here?" Harper asked, surprised to see him.

"This is where SID sent us."

"Something's wrong," said Harper. "That case doesn't belong in robbery."

Schiller was having a rough time of his own with Sgt. Jim Maier, head of a task force designed to stop tourist robbers, and robbery Det. Iris Deegan. Three times during the interview, Deegan interrupted to warn him it was a crime to file a false complaint. The police don't have time to ride around pursuing every wild story we hear, she said.

Schiller might have expected skepticism from his State Farm claims agent, but not from the police. "Listen," he said, "do me one favor. Follow up on Du Bois's leads. These are dangerous people; other people could be harmed. If you're wasting your time, throw me in jail." Why on earth weren't Deegan and Maier eager to arrest these guys? Why were they so insulting? Why were they making the victim feel like a criminal?

Finally he had to ask: "Do you think I'm making this whole thing up? Do you think, what, I don't know, I've got this huge imagination?"

"Yeah," Deegan said, "we think you're making it up."

There was still the question of the polygraph, which Ed Du Bois had requested from the outset. No one seemed to recall that now. Sergeant Maier turned around and challenged Schiller: Would he be willing to undergo a polygraph?

"Give it to me now!" he said. "I've got nothing to hide!" This was, in fact, just why he'd stayed over an extra day.

There was a catch, though. The test would have to wait, not until later that day or anytime over the weekend. He'd have to come back the following Tuesday. Weeks ago, when he'd set up the trip, SID knew he had a narrow window. It was Friday and he'd already extended the visit, and on his own dime. He was broke. The Sun Gym gang had his money and probably was looking for him.

To hell with them all. He was going home.

Schiller emerged from the interview room looking stunned and close to tears. Maier followed him and told Du Bois that unless his client was in Miami the following Tuesday for more interviews and a polygraph, the police weren't going to take his complaint any further. One look at Schiller, and Du Bois knew he wasn't about to stay around for more of whatever they'd just dished out.

Du Bois turned to Maier: "Tell me, just what is wrong with this case?"

"I don't speak to private eyes," the sergeant answered.

"Is that a personal policy or a department policy?" asked Du Bois. The conversation was giving him chills. He had a long history with Metro police; he'd worked as an outside contractor hundreds of times. He'd solved capital cases. Now they thought his client was a laughingstock, and they lacked even the decency to offer some crumb to pacify him. Yet the crimes against Schiller involved violations of almost every Florida felony statute.

Du Bois was running out of time. He drove Schiller back to his office and called the Miami bureau of the FBI, but his contact there was out of town. Next he called Fred Taylor, director of the Metro-Dade Police Department. Du Bois knew Taylor socially and professionally. The director listened as Du Bois detailed their treatment at the robbery bureau and said he'd put in a call to robbery Cmdr. Pete Cuccaro. Minutes later Cuccaro was on the line, assuring the detective he had his best robbery people -- Deegan and Maier -- working the case. Du Bois rolled his eyes.

Late in the afternoon back at his hotel, Schiller finished packing for his flight. Then he placed a call to JoMar Properties. He hadn't spoken to his former friend and employee Jorge Delgado since before the kidnapping. Now, in between expletives, he announced that he'd gone to the police with accusations of kidnapping, extortion, and attempted murder. Not only that, but he'd turned over copies of forged documents and Sun Gym checks. He also made a call to John Mese. Mese hung up on him.

Then Schiller left to board his flight.

In her defense, it must be said, Det. Iris Deegan had some cause -- not much, but some -- to doubt Schiller's account. Why had he waited four months after the alleged crime to make a complaint? Why had he agreed to a financial settlement before coming to the police? To her, Schiller's tale was "bizarre ... like something you read about in a book." On top of that, SID already had rendered its own verdict on the story. And frankly, in Miami Colombians were almost always associated with cocaine and drug trafficking. Schiller had told her that a portion of the stolen $1.26 million, which he'd invested in offshore and Swiss accounts, belonged to his wife's Colombian relatives.

Wednesday, April 26, 1995

Mese,

How can you be so complacent about the mess you are in? I called you Friday, Monday, and Tuesday and you still have not contacted your attorney. Are you stupid or naive enough to think this problem is going to go away?

You decide, return what is not yours now! or face the music.

Tick, tick, tick ...

Schiller

On the same day Schiller sent his note to Mese warning that his time was running out, Detective Deegan began investigating Schiller's claims, despite the fact that he had left for Colombia in disgust without waiting for a polygraph test as the cops had requested.

Deegan paid a visit to Schiller's home in Old Cutler Cove. The house appeared abandoned; indeed the Sun Gym gang had emptied it weeks before. When Deegan interviewed Schiller's neighbors, they identified Lugo from a police photo lineup. Yes, he was a G-man, they said. Yes, they'd accepted UPS deliveries for him, packages addressed to Marc Schiller. Yes, they recalled, Schiller and his family had disappeared sometime before the previous Thanksgiving. Check ... check ... check. Right down the list of allegations.

By May 4 Deegan was at last convinced that something serious, something possibly criminal, had taken place. She filed her third (it would be her final) report on Case No. 195623-R, noting that she'd subpoenaed Schiller's bank and credit-card accounts, as well as UPS invoices and delivery notices. She'd also asked American Express to supply statements about purchases made between November 1994 and January 1995. Then she moved on to her other robbery cases. She never questioned the suspects. When Du Bois called to check on her progress, she said she was waiting for the records requests to be processed and delivered. End of story.

"Why do you keep investigating my client?" he asked. "Why don't you go out on the street, show your badge to these guys, read them their Miranda rights, and ask them some questions before these animals strike again?"

"Are you trying to tell me how to do my job?" she countered.

"No, but it sure doesn't seem like you're doing it right." He was sorry, he said, that he hadn't thought to bring her a bloody victim, warehouse videos, or signed confessions.

By now Du Bois had presented his facts and documents to FBI agent Art Wells, a twelve-year veteran. Wells thought, and later said, "It's like something you see in a made-for-TV movie." He chose not to pursue an investigation either. Du Bois had never flown into the teeth of such bureaucracy. He kept on predicting, to anyone in law enforcement who would still take his calls, that the gang would target some new victim. He couldn't figure it out. He'd spent 35 years working in Miami, assisting the police. He'd never cried wolf. But he knew this pack of wolves was gathering at somebody's door, and he prayed his family wouldn't get in their way.

Du Bois was right about the wolves. Lugo already had begun searching for his next victim, and this time he didn't have to look beyond Sun Gym. Winston Lee, a vegetarian from Jamaica, came in regularly to lift weights. Lee owned a prosperous auto-repair shop in Opa-locka, and though he wasn't nearly as rich as Marc Schiller, he was rich enough. And besides, he'd aggravated Doorbal, who was convinced he'd heard the Jamaican making fun of his intellect. Worse than that, Lugo said, Lee supposedly sold drugs in the black community. That was enough for Jorge Delgado. He was in. This time, though, they'd keep Stevenson Pierre and Carl Weekes out of it; they'd done nothing but prove their incompetence.

By April, Lugo had a concept. He'd borrow a uniform and truck from another member of the gym and have Delgado pose as a UPS delivery man at Lee's front door. Then Lugo and Doorbal and would rush the house when Lee opened the door. Next stop for Lee? A warehouse Lugo planned to lease in Hialeah for the next round of torture.

To his mistress Sabina, however, Lugo furnished a different story: The CIA wanted to capture Winston Lee, known Palestinian terrorist. And on behalf of the Company, he recruited her help. The plan gave her pause, but then she thought about her patriotism toward her new country and her gratitude toward Lugo, who'd gotten her out of stripping at Solid Gold and into a rent-free love nest. She accepted the mission.

With Sabina in the mix, Lugo devised Plan No. 2. Lugo would move her next door to Lee, and she'd befriend him using her considerable charms. Eventually she would lure him to her apartment, at which time Lugo and Doorbal would burst in and subdue him. They'd take him to an agency warehouse, where the CIA would secure him and take him away to the place where they put terrorists.

Meanwhile Lee continued his workouts at the gym, oblivious to the plans. He thought, in fact, that Lugo and Doorbal were okay guys. But the Okay Guys were staking out his Miami Lakes townhouse. They photographed the building from the road and from his shrubbery. They took pictures of every window and door, as well as closeups of his outdoor circuit-breaker box and the junctions where his phone lines ran into the house.

But the gang had to abandon Winston Lee as a target. He traveled frequently to Jamaica and they couldn't fix a date when he'd be home. Nor was Lugo able to secure a space for Sabina in the building. It was just too confusing.

Then Adrian Doorbal found another target.

Doorbal had at last won the impossibly beautiful Beatriz Weiland, the exotic dancer from Hungary who entertained at Solid Gold. His great looks and bodacious physique finally were paying off big-time. He had a gorgeous stripper -- maybe the hottest stripper in the joint! -- naked in bed. What didn't he have? An erection. The same problem that had plagued him in previous months reappeared. He paid another visit to the Coral Springs physician who specialized in treating steroid-induced impotence, received hormone injections, and soon was performing like a champ.

At Beatriz's place one day, Doorbal began leafing through a photo album. Staring out from the pages was a matronly lady lounging in front of a car as bright as the sun. The woman was Beatriz's mother, but it was the car that caught Doorbal's attention. Who owns it? he asked. Beatriz pointed to another photo in the album and identified the owner, a fellow Hungarian named Frank Griga. He'd been one of her lovers and she still spoke of him affectionately. Griga had achieved fantastic wealth through the phone-sex business, and was the most generous man she'd ever known. The sun-bright car was his $250,000, 1991 Lamborghini Diablo.

The son of a Hungarian diplomat, Griga was born in Berlin in 1961. He moved to New York City in the mid-Eighties, working first as a car washer then as a foreign-car mechanic. But he wasn't destined to toil under a hood. In 1988 he moved to Miami and got a job in sales at Prestige Imports, a luxury-car dealership in North Miami Beach. Working among all those gleaming machines -- Lotuses, Ferraris, Mercedes, Rolls-Royces -- proved frustrating, however. He wanted to own them, not sell them.

Socially active in Miami's tiny Hungarian community, Griga joined a group of local investors, some of whom he'd known from childhood, in the burgeoning 800- and 900-number phone-line markets. He began with 976-CARS, which charged callers for information on used autos. Next he delved into weather-information lines for boaters and surfers. Even more profitable were the 976-SEX lines he established with Hungarian friend Gabor Bartusz. They advertised their services in Penthouse and Hustler, and callers spent up to five dollars per minute to engage in sexually explicit conversations with telephone actors and actresses. Some of Griga's girlfriends appeared in the advertisements, as did some of his cars. Many Hungarians in Miami thought he was the Alexander Graham Bell of phone sex. The business earned Griga and Bartusz a fortune. In 1994 alone, they took in three million dollars.

Griga began to collect luxury automobiles, among them a $200,000 royal blue Vector, a rare, handmade, experimental sports car; a Dodge Stealth for running errands; and the Lamborghini Diablo. He also bought a $700,000 mansion on the Intracoastal Waterway in tony Golden Beach, one of Florida's most exclusive communities. He owned a yacht, Foreplay, and a condo in the Bahamas.

His girlfriends were beautiful, as sensual and sculpted as the cars he owned. He preferred babes, some of them strippers, and after he and Beatriz had parted ways, she introduced him to Krisztina Furton at Crazy Horse II, a Fort Lauderdale strip joint. The two quickly fell in love and became inseparable.

Krisztina, from a Hungarian military family, was 21 years old when she came to Miami in 1993. She was penniless and spoke no English, and arrived with only the promise of a job as an exotic dancer, a typical steppingstone for pretty foreign girls who lack green cards. (In the high-end clubs, the women work for tips alone, thus no W-2 forms.) At Crazy Horse II the slender brunette learned about American life and economics. She saved up for implants and a nose job as well. Within a year she had the money for both

Doorbal also learned from Beatriz that Griga occasionally hung out at Solid Gold, enjoying the scenery and scouting for models for his phone-line advertisements. An entrepreneur, he was always looking for new investment opportunities.

But while Doorbal was thrilled with Beatriz, she was having doubts about him. She was bothered by the weapons in his car, and in his townhouse. "Hey, Miami's a dangerous place," he told her. "I need them for protection." Still she wasn't comfortable. To compound matters, he continued to pester her with questions about Frank Griga. It was as if he were writing a book on the man. He wanted to meet Griga, he said. He and Lugo wanted to do business with him. But Beatriz didn't talk much to Frank anymore; besides, she thought Krisztina was jealous of her past with him. To placate Doorbal, she said she'd ask her estranged husband, Attila Weiland, to do the honors.

Weiland was working as a small-time travel agent. His office was located conveniently near Dr. Lief's, where Doorbal was scheduled to receive another magical injection. Weiland agreed to meet Doorbal in the doctor's parking lot. He understood that time was money to a busy entrepreneur and didn't think it odd to meet his ex-wife's lover at a doctor's office. He too was dying to develop a business connection with Griga. At Hungarian social functions, Weiland often asked him for advice. "The first $100,000 is the hardest, Attila," Griga would say. And he offered to lend a hand if Weiland had a worthy business proposition.

Weiland didn't quite grasp the proposal Doorbal wanted to pitch. Hell, Doorbal admitted, he didn't understand the specifics as well as his cousin, Danny Lugo. He just knew it was a bona fide moneymaker. It had to do with phone lines in India, and a company called Interling International. Perfect, thought Weiland; Griga was familiar with phone-line success, and he was looking to branch out from the phone-sex business. This thing with Doorbal and his cousin might be the ticket. Weiland offered to put in a good word.

By now, though, Beatriz was quite fed up. She was suspicious of Doorbal's apparently limitless income. She didn't believe for one minute that he and Lugo were international tycoons. He tried to tell her he'd never worked so hard in his life, that he was working on one last big score that would allow him to retire and live on a private island. He figured it would take two months, tops. Yet as far as Beatriz could tell, all he seemed to do was work out at Sun Gym and hang out at Solid Gold. Finally he made the big confession: Like Lugo, he was an agent with the CIA. She didn't buy it. Okay, he explained to her, "I'm a subcontractor to the CIA, through Danny Lugo."

The guns, the impotence, the unexplained funds, the supposed CIA connection -- Beatriz decided Adrian Doorbal wasn't mysterious at all. He was ridiculous, and maybe he was dangerous. She amicably dissolved their relationship. Doorbal took the breakup well; he still had Attila Weiland.

In May 1995 Doorbal suddenly lobbied "Big Mario" Sanchez, who'd earned $1000 for his part the afternoon they kidnapped Marc Schiller, to become his workout partner, a serious commitment of time and interest in the world of huge muscle guys. These days Doorbal was driving a pearl-color Nissan 300 ZX. He liked it fine, but what he really wanted, he told his newest pal, was a bright-yellow Lamborghini Diablo. Before long Doorbal told Sanchez he and Lugo had another "job" coming up and asked if he wanted to serve as an "intimidator." Sanchez said he never wanted to get involved in anything like that abduction thing again. Doorbal offered him $5000, but Sanchez said no.

Doorbal and Lugo needed assistance to pull off another takedown. They were getting so desperate they even considered Carl Weekes. But Weekes's self-improvement journey to Miami hadn't gone well. He was back to boozing, and he'd recently been arrested for carrying a concealed weapon, a gun he bought because he was terrified of the Sun Gym gang. He suspected he'd been recruited to Miami by the gang specifically to kidnap Schiller. Only one good thing had come out of that nastiness: He did get $50,000. He now was driving a BMW.

Lugo took Weekes to Solid Gold and told him Doorbal had targeted another victim. Like Sanchez, Weekes declined the offer. He thought they might be planning to kill him, along with the Hungarian.

"Look, Sabina," began Lugo one day in their Main Street apartment after he'd returned from another trip to CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. "You always ask if you can help me. Well, I need your help now." With those words Lugo conscripted Sabina Petrescu into her second undercover operation for the United States of America. This time, he told her, it was the FBI that wanted him to capture someone, some guy named Frank Griga, a Golden Beach businessman who used women for sex, especially Hungarian women. Besides that, he was circumventing U.S. tax laws. (Lugo confided that he might personally extract some money from Griga before turning him over to the FBI.)

Sabina was excited about this assignment. She was aching to display her patriotism, she was bored, she was ... dim. (She was that special type of woman about whom a prosecutor would one day say in court: "You see, God blessed Sabina Petrescu with a beautiful face and a beautiful body, but not with any book smarts or common sense.") She'd felt let down when the operation to capture Palestinian terrorist Winston Lee folded. She'd begged to participate in the surveillance missions on him.

Lugo filled her in on the new job. They would snatch Griga and his girlfriend from Griga's mansion. After Lugo and Doorbal entered the front door, Sabina would wait until she saw the garage door open and Doorbal driving a Lamborghini out into the driveway. Then she would back Lugo's gold Mercedes into the garage. Griga and the girlfriend would be stashed in the trunk of the Mercedes. They'd be handcuffed, gagged, tranquilized, and blindfolded.

"When you see it, Sabina, you will be frightened," cautioned Lugo. "They will be tied up, they'll have tape over their mouths, but they'll be okay."

"What about the girl?" she asked. "Why her? She doesn't have anything to do with this. He's the one the FBI wants."

"She's the girlfriend and she'll know," said Lugo. "We can't just let her go; she would talk. But we won't hurt her."

On Friday, May 19, Attila Weiland drove out to the Golden Beach house to attend a surprise party for Frank Griga's 33rd birthday. Krisztina Furton had arranged the party with Judi and Gabor Bartusz, their closest friends. A dozen Hungarians were in attendance, and Weiland made sure to take Griga aside and tell him he knew a couple of guys who wanted to pitch a business deal. Sure, Griga said, he'd listen. They agreed that Weiland would bring them by the next day.

At 6:30 the following evening, Attila Weiland sat in the back seat of Lugo's Mercedes, giving directions to the house. Up front with Lugo was his "cousin" Adrian Doorbal. As they pulled into the driveway, a mechanic was working on Griga's canary-yellow Lamborghini, the car Doorbal coveted.

For this meeting the weight lifters had abandoned their muscle shirts and jeans in favor of tailored suits and ties. They looked like a pair of Wall Street dynamos in their elegant threads. Doorbal even wore Marc Schiller's Presidential Rolex. Griga, dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, was taken aback by their striking entrance. He even pulled Weiland aside to tell him these guys sure did know how to dress to impress. And they seemed like nice guys, to boot.

Lugo did the talking, explaining that he and Doorbal were offering a lucrative investment opportunity through Interling International, Inc. (which actually was a legitimate telecommunications company expanding into India). He provided authentic Interling color brochures with pie charts and text indicating phenomenal growth potential; its only real competition was AT&T. They were seeking only serious investors; he'd have to chip in between $500,000 and $1,000,000 to get in. Griga was interested. He might even want to invest more than a million, particularly if they could develop some action with cell-phone use in South Asia. Lugo agreed to look into that possibility.

As a bonus, Krisztina gave Lugo and Doorbal a guided tour of the mansion, a perfect ending to the visit.

On the drive home Doorbal was psyched. He told Weiland they'd remember it was he who'd made this introduction possible, that he'd be taken care of if the deal went through. The future looks bright, the future looks bright, Doorbal kept repeating. They dropped Weiland off at his apartment. They had a lot of work to do back on Main Street.

Once they arrived home, Lugo told Sabina the abduction of the Golden Beach couple would "go down tomorrow." That evening she watched in her living room as he and Doorbal packed their FBI equipment: guns, handcuffs, rope, syringes, and Rompun, a tranquilizer used to sedate horses and other large animals.

On the way to Griga's house the next morning, Sunday, May 21, they realized they'd forgotten duct tape, so they pulled into a store on Hallandale Beach Boulevard and Doorbal got out of the Mercedes. Sabina waited in the car with Lugo when suddenly he let out a shriek; Doorbal's gun clearly was visible in the back of his pants. Lugo raced to intercept him before he entered the store. Even in South Florida, a handgun rising from one's waistband is sometimes cause for alarm.

They drove on toward Golden Beach without incident, and Lugo called Griga from his cell phone to ask if they could stop by. No problem. Lugo shoved a CD into the car stereo and played the Eagles' "Life in the Fast Lane." Now they had a soundtrack for the mission as they drove through the security gate. From the back seat Sabina watched the men exchange glances and grins. She'd never seen them look so happy.

When they arrived at the house, the two men quickly got out of the car. She saw Lugo, who was carrying a laptop computer in one hand, stick a gun into the waistband of his nylon sports pants with the other. As he and Doorbal approached the front door, Lugo clumsily knocked over a garbage can. Krisztina answered the door.

Sabina waited nervously for five, ten, fifteen minutes. She imagined the plan unfolding inside the house: Doorbal would take care of the woman while Lugo handled Griga. But the garage door never opened. Instead Lugo and Doorbal came out empty-handed.

"We should have done it! We should have done it!" Doorbal yelled on the drive back to Miami Lakes. No, argued Lugo, the timing wasn't right. But he had a new plan. He got on the cell phone again and called Griga to invite him and Krisztina to dinner that evening. They could meet in Miami Lakes, at Shula's Steak House, and talk over the Interling deal.

Griga accepted the invitation for dinner, even though the computer he'd just received as a gift seemed odd to him, inappropriate. He'd sat through plenty of preliminary business discussions over the years, and had never been rewarded like this. He called Attila Weiland for an explanation. Weiland in turn called Doorbal, who assured him the computer was merely an expression of their desire to do business, that they really liked the guy.

After Griga heard back from Weiland, he remained unsure. The gesture was over the top, but he and Krisztina would still join the two businessmen at Shula's. Who, after all, looks a gift horse in the mouth?

That evening, before dinner, Sabina sat on Doorbal's couch as Lugo explained her role to her. When the foursome returned from the steak house, Sabina was to pretend she was Lugo's Russian wife. She would befriend Krisztina, "make her feel good," until the men lured Griga into another room to take him down.

Sabina waited for hours. Lugo showed up at midnight alone, looking "distressed" and saying the dinner went well but he'd had a fight with Doorbal. Yet another mission aborted.

Over the next few days, Griga studied the Interling International corporate information package. He even ran the proposal by a stockbroker friend for his opinion. Lugo and Doorbal appeared well-off, the investment looked solid, and Lugo seemed to have an excellent grasp of the stock market and finances. Griga decided he'd meet again with the musclebound businessmen.

On the morning of Wednesday, May 24, 1995, Griga traveled to Allied Marine in Fort Lauderdale, where he bought $800 in Jet Ski accessories -- helmets, a kidney belt, a case of marine oil. At 6:30 p.m. he went to the Johnson Street boat ramp in Hollywood Beach with Lloyd Alvarez, a friend who sold and worked on personal watercraft. Alvarez dropped him off to take delivery of a $6000 Sea-Doo XP800, then drove back to the house to meet him after a test ride down the inland waterway to his back-yard dock. When Griga rode up with the Sea-Doo, Krisztina took it out for a spin before they hoisted it out of the water.

At about 8:00 p.m., Alvarez met two visitors, Danny and Adrian, who'd come by the house to accompany Frank and Krisztina to dinner. While Griga went upstairs to change, the men downstairs discussed Jet Skis and electronics. Lugo and Doorbal were fascinated by Alvarez's digital beeper and its displays. They talked about owning a fledgling watercraft business of their own, and asked Alvarez for his business card.

Some 45 minutes later, Krisztina and Griga came downstairs. She was wearing a red-leather miniskirt and jacket with a large gold eagle embossed on the back. She also wore red heels and carried a matching red-leather handbag. Griga wore a blue-denim shirt, jeans, and cowboy boots. But just as they were departing, someone knocked on the door. It was neighbor Judi Bartusz, out walking her dog. She'd seen all the cars and stopped by to say hello. She knew Lloyd Alvarez and was introduced to Lugo and Doorbal, guys with a phone deal in South Asia. Griga said he'd be sure to tell Judi's husband Gabor more about it after tonight's business dinner.

And more company came: Eszter Toth, the Hungarian housekeeper, unexpectedly arrived with her four-year-old. She too deserved an introduction. Then the phone rang; it was Griga's stockbroker friend. No, he couldn't join them for dinner; he was tied up with work. But he'd speak to Griga tomorrow about the Interling deal.

Griga began to usher the small crowd out of his foyer. "Happy Birthday" banners from the surprise party still hung from the ceiling in the dining room. He patted the dog, Chopin, goodbye, then got into the Lamborghini Diablo with Krisztina, and followed Doorbal and Lugo to Shula's Steak House.

When Judi Bartusz got home, she unleashed her dog and went to talk to her husband. She told him she'd stopped in at Griga's just as the couple was leaving on a dinner date. She thought Frank seemed nervous, and she didn't like his new partners, Adrian and Danny.

"What's wrong with them?" asked Gabor.

"I'm not sure why," said Judi, "but Frank wasn't the same. I think Frank is in a world of trouble."

Hungarian businessman Frank Griga and his girlfriend Krisztina Furton were not so fortunate as Marc Schiller. Shula's was closed by the time they arrived, so the party moved to Doorbal's Main Street townhouse apartment, one flight of stairs above Ritchie Swimwear, a bikini shop.

As Lugo and Furton watched television on Schiller's 50-inch Mitsubishi, Doorbal and Griga walked into another room to talk business. Soon, though, even Schiller's SurroundSound speakers couldn't muffle the discordant noises rising from the next room. A fierce argument was under way. Then loud crashing noises. Lugo and Krisztina rushed in and found the two men in a vicious fight. Blood was running down Griga's head where he'd been smashed above the ear with a hard, blunt object. Krisztina glanced around the room. Blood splattered the computer screen and the sliding glass doors. There was blood on the walls. It was all Griga's.

As she watched in horror, Doorbal took her lover in a headlock and proceeded to strangle him. She screamed. Lugo clamped a hand over her mouth and tackled her. She was handcuffed and her feet bound with duct tape. They wrapped the tape over her eyes and mouth as well. Then Doorbal injected her with Rompun. Within moments she was unconscious. They pulled a ninja hood down over her head. For good measure they gave Griga a hefty squirt of Rompun, too.

Targets apprehended. Mission accomplished at last!

After taking a breather and surveying the messy scene, Lugo and Doorbal checked on their prize catch, the man who would soon be hauled off to a warehouse where he would gently be persuaded to provide them with untold riches; the man who, along with his luckless girlfriend, would also be dead before long.

To their everlasting disappointment they discovered they'd overdone it: Griga was dying. And they hadn't gotten a single penny out of him. They'd taken everything from Schiller but couldn't kill him. Maybe someday they'd get it right.

At the moment, though, they had Krisztina, and she was alive. Eventually, of course, they'd have to kill her too, a witness to her boyfriend's murder and all. But first they wanted information about the house, particularly the front-door keypad numbers.

In the meantime Griga presented a disposal problem. They dumped him into Doorbal's bathtub as the rest of his blood drained out in a spiral.

Two miles away Jorge Delgado waited at home for a phone call. He was supposed to assist Lugo and Doorbal once they subdued Griga and Krisztina, then help transport the couple to Lugo's warehouse for a preliminary round of torture and extortion, just as they'd done with Marc Schiller. But the phone never rang, so he went to bed.

Sabina woke up sometime in the night and realized Lugo hadn't returned home from his dinner with the "bad Hungarian man and his girlfriend." She got up and found her secret agent man on the living-room couch. He was drinking in the darkness and crying softly. Doorbal had done "something crazy," he moaned.

Sabina asked if the man and woman were still alive.

Lugo turned to face her. "Do you really want to know, Sabina?" he said. She'd never heard that tone before. He stared into her blue eyes. "Are you sure you really want to know?"

Information for this story was drawn from interviews with principal characters, investigative reports, court documents, and trial testimony. Next week: The Sun Gym gang must dispose of the bodies; a quickie wedding and an alibi could save the day; and kidnap victim Marc Schiller returns to Miami and gets far more than he bargained for.